[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, March 13th, 2025

| Time | Event |

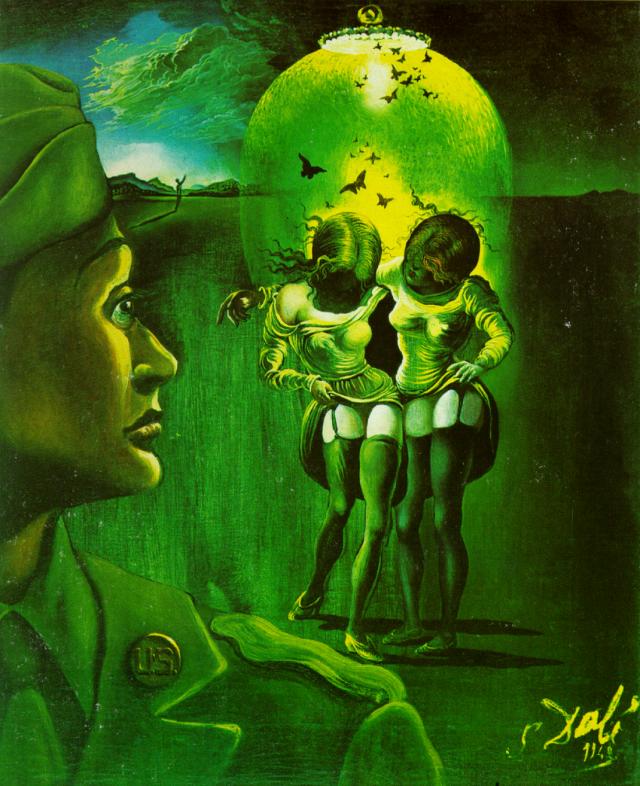

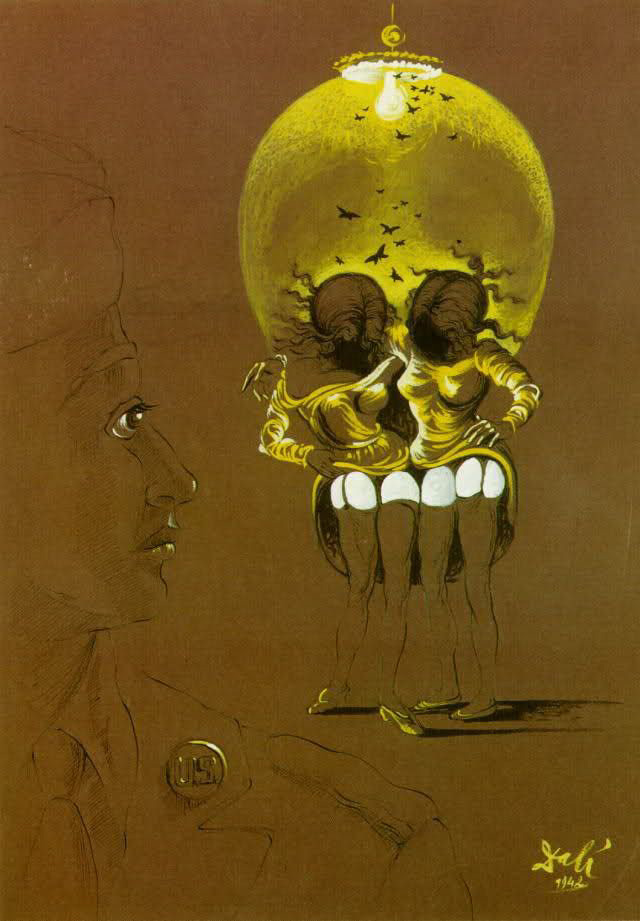

| 4:57a | When Salvador Dalí Created a Chilling Anti-Venereal Disease Poster During World War II

As a New York City subway rider, I am constantly exposed to public health posters. More often than not these feature a photo of a wholesome-looking teen whose sober expression is meant to convey hindsight regret at having taken up drugs, dropped out of school, or forgone condoms. They’re well-intended, but boring. I can’t imagine I’d feel differently were I a member of the target demographic. The Chelsea Mini Storage ads’ saucy regional humor is far more entertaining, as is the train wreck design approach favored by the ubiquitous Dr. Jonathan Zizmor. Public health posters were able to convey their designated horrors far more memorably before photos became the graphical norm. Take Salvador Dalí’s sketch (below) and final contribution (top) to the WWII-era anti-venereal disease campaign.

Which image would cause you to steer clear of the red light district, were you a young soldier on the make? A portrait of a glum fellow soldier (“If I’d only known then…”)? Or a grinning green death’s head, whose choppers double as the frankly exposed thighs of two faceless, loose-breasted ladies? Created in 1941, Dalí’s nightmare vision eschewed the sort of manly, militaristic slogan that retroactively ramps up the kitsch value of its ilk. Its message is clear enough without: Stick it in—we’ll bite it off! (Thanks to blogger Rebecca M. Bender for pointing out the composition’s resemblance to the vagina dentata.) As a feminist, I’m not crazy about depictions of women as pestilential, one-way deathtraps, but I concede that, in this instance, subverting the girlie pin up’s explicitly physical pleasures might well have had the desired effect on horny enlisted men. A decade later Dalí would collaborate with photographer Philippe Halsman on “In Voluptas Mors,” stacking seven nude models like cheerleaders to form a peacetime skull that’s far less threatening to the male figure in the lower left corner (in this instance, the very dapper Dalí himself). Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014. Related Content: When Salvador Dali Met Sigmund Freud, and Changed Freud’s Mind About Surrealism (1938) When The Surrealists Expelled Salvador Dalí for “the Glorification of Hitlerian Fascism” (1934) Destino: The Salvador Dalí — Walt Disney Animation That Took 57 Years to Complete Ayun Halliday is an author, homeschooler, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. |

| 9:00a | Watch the Only Time Charlie Chaplin & Buster Keaton Performed Together On-Screen (1952) Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton were the two biggest comedy stars of the silent era, but as it happened, they never shared the screen until well into the reign of sound. In fact, their collaboration didn’t come about until 1952, the same year that Singin’ in the Rain dramatized the already distant-feeling advent of talking pictures. That hit musical deals with once-famous artists coping with a changing world, and so, in its own way, does Limelight, the film that finally brought Chaplin and Keaton together, dealing as it does with a washed-up music-hall star in the London of 1914. A specialist in downtrodden protagonists, Chaplin — who happened to have made his own transition from vaudeville to motion pictures in 1914 — naturally plays that starring role. Keaton appears only late in the film, as an old partner of Chaplin’s character who takes the stage with him to perform a duet at a benefit concert that promises the salvation of their careers. In reality, this scene had some of that same appeal for Keaton himself, who had yet to recover financially or professionally after a ruinous divorce in the mid-nineteen-thirties, and had been struggling for traction on the new medium of television. Though Limelight may be a sound film, and Chaplin and Keaton’s scene may be a musical number, what they execute together is, for all intents and purposes, a work of silent comedy. Chaplin plays the violin and Keaton plays the piano, but before either of them can get a note out of their instruments, they must first deal with a series of technical mishaps and wardrobe malfunctions. This is in keeping with a theme both performers essayed over and over again in their silent heyday: that of the human being made inept by the complications of an inhuman world. But of course, Chaplin and Keaton’s characters usually found their ways to triumph at least temporarily over that world in the end, and so it comes to pass in Limelight — moments before the hapless violinist himself passes on, the victim of an onstage heart attack. In the real world, both of these two icons from a bygone age had at least another act ahead of them, Chaplin with more films to direct back in his native England and Europe, and Keaton as a kind of living legend for hire, called up whenever Hollywood needed a shot of what had been rediscovered — not least thanks to TV’s re-circulation of old movies — as the magic of silent pictures. Related content: Discover the Cinematic & Comedic Genius of Charlie Chaplin with 60+ Free Movies Online A Supercut of Buster Keaton’s Most Amazing Stunts When Charlie Chaplin First Spoke Onscreen: How His Famous Great Dictator Speech Came About Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/03/13 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |