[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, April 11th, 2025

| Time | Event |

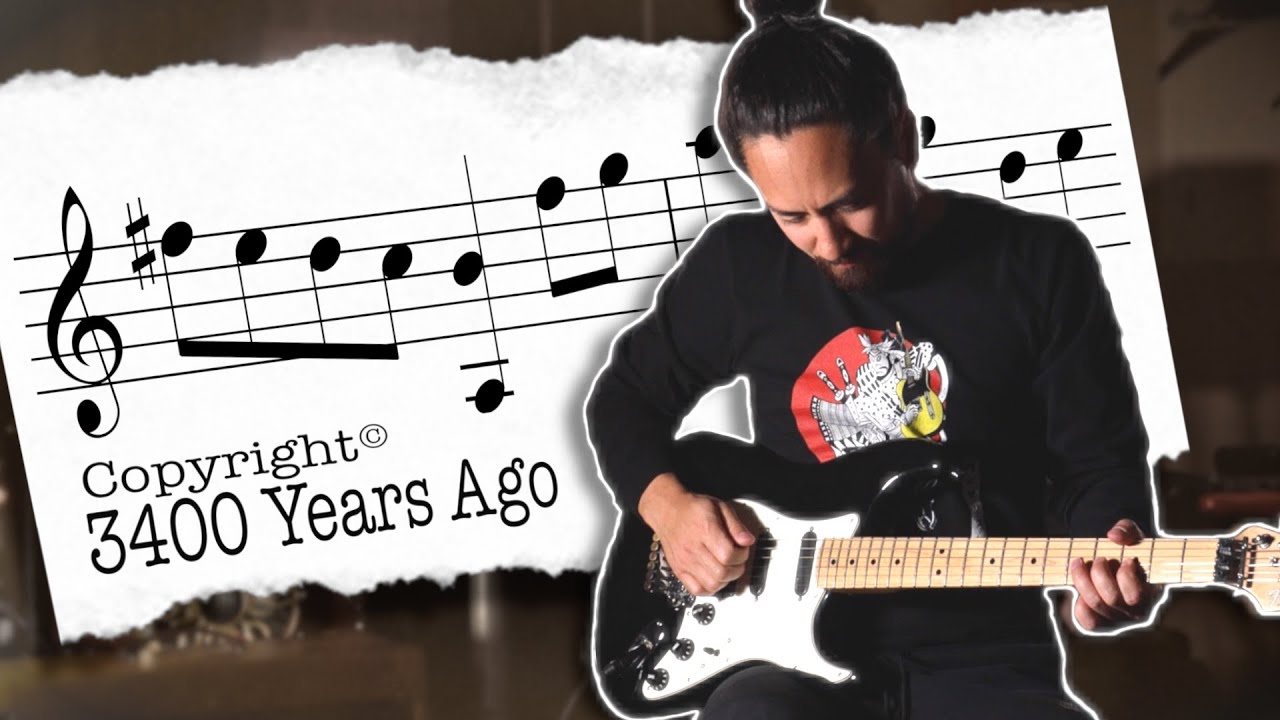

| 9:00a | Hear the World’s Oldest Known Song, “Hurrian Hymn No. 6” Written 3,400 Years Ago Do you like old timey music? Splendid. You can’t get more old timey than Hurrian Hymn No. 6, which was discovered on a clay tablet in the ancient Syrian port city of Ugarit in the 1950s, and is over 3400 years old. Actually, you can — a similar tablet, which references a hymn glorifying Lipit-Ishtar, the 5th king of the First Dynasty of Isin (in what is now Iraq), is older by some 600 years. But as CMUSE reports, it “contains little more than tuning instructions for the lyre.” Hurrian Hymn No. 6 offers meatier content, and unlike five other tablets discovered in the same location, is sufficiently well preserved to allow archaeologists, and others, to take a crack at reconstructing its song, though it was by no means easy. University of California emeritus professor of Assyriology, Anne Kilmer spent 15 years researching the tablet, before transcribing it into modern musical notation in 1972. Hers is one of several interpretations YouTuber Hochelaga samples in the above video. While the original tablet gives specific details on how the musician should place their fingers on the lyre, other elements, like tuning or how long notes should be held, are absent, giving modern arrangers some room for creativity. Below archaeomusicologist Richard Dumbrill explains his interpretation from 1998, in which vocalist Lara Jokhader assumes the part of a young woman privately appealing to the goddess Nikkal to make her fertile: Here’s a particularly lovely classical guitar spin, courtesy of Syrian musicologist Raoul Vitale and composer Feras Rada… And a haunting piano version, by Syrian-American composer Malek Jandali, founder of Pianos for Peace: And who can resist a chance to hear Hurrian Hymn No. 6 on a replica of an ancient lyre by “new ancestral” composer Michael Levy, who considers it his musical mission to “open a portal to a time that has been all but forgotten:” I dream to rekindle the very spirit of our ancient ancestors. To capture, for just a few moments, a time when people imagined the fabric of the universe was woven from harmonies and notes. To luxuriate in a gentler time when the fragility of life was truly appreciated and its every action was performed in the almighty sense of awe felt for the ancient gods. Samurai Guitarist Steve Onotera channels the mystery of antiquity too, by combining Dr. Dumbrill’s melody with Dr. Kilmer’s, trying and discarding a number of approaches — synthwave, lo-fi hip hop, reggae dub (“an absolute disaster”) — before deciding it was best rendered as a solo for his Fender electric. Amaranth Publishing has several MIDI files of Hurrian Hymn No. 6, including Dr. Kilmer’s, that you can download for free here. Open them in the music notation software program of your choice, and should it please the goddess, perhaps yours will be the next interpretation of Hurrian Hymn No. 6 to be featured here on Open Culture… Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2022. Related Content What Ancient Greek Music Sounded Like: Hear a Reconstruction That is ‘100% Accurate’ The Evolution of Music: 40,000 Years of Music History Covered in 8 Minutes A Modern Drummer Plays a Rock Gong, a Percussion Instrument from Prehistoric Times - Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday. |

| 9:00a | How Chinese Characters Work: The Evolution of a Three-Millennia-Old Writing System Contrary to somewhat popular belief, Chinese characters aren’t just little pictures. In fact, most of them aren’t pictures at all. The very oldest, whose evolution can be traced back to the “oracle bone” script of thirteenth century BC etched directly onto the remains of turtles and oxen, do bear traces of their pictograph ancestors. But most Chinese characters, or hanzi, are logographic, which means that each one represents a different morpheme, or distinct unit of language: a word, or a single part of a word that has no independent meaning. Nobody knows for sure how many hanzi exist, but nearly 100,000 have been documented so far. Not that you need to learn all of them to attain literacy: for that, a mere 3,000 to 5,000 will do. While it’s technically possible to memorize that many characters by rote, you’d do better to begin by familiarizing yourself with their basic nature and structure — and in so doing, you’ll naturally learn more than a little about their long history. The TED-Ed lesson at the top of the post provides a brief but illuminating overview of “how Chinese characters work,” using animation to show how ancient symbols for concrete things like a person, a tree, the sun, and water became versatile enough to be combined into representations of everything else — including abstract concepts. In the Mandarin Blueprint video just above, host Luke Neale goes deeper into the structure of the hanzi in use today. Whether they be simplified versions of mainland China or the traditional ones of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and elsewhere, they’re for the most part constructed not out of whole cloth, he stresses, but from a set of existing components. That may make a prospective learner feel slightly less daunted, as may the fact that roughly 80 percent of Chinese characters are “semantic-phonetic compounds”: one component of the character provides a clue to its meaning, and another a clue to its pronunciation. (Not that it necessarily makes deciphering them an effortless task.) In the distant past, hanzi were also the only means of recording other Asian languages, like Vietnamese and Korean. Still today, they remain central to the Japanese writing system, but like any other cultural form transplanted to Japan, they’ve hardly gone unaltered there: the NativLang video just above explains the transformation they’ve undergone over millennia of interaction with the Japanese language. It wasn’t so very long ago that, even in their homeland, hanzi were threatened with the prospect of being scrapped in the dubious name of modern efficiency. Now, with those aforementioned almost-100,000 characters incorporated into Unicode, making them usable throughout our 21st-century digital universe, it seems they’ll stick around — even longer, perhaps, than the Latin alphabet you’re reading right now. Related content: What Ancient Chinese Sounded Like — and How We Know It: An Animated Introduction Discover Nüshu, a 19th-Century Chinese Writing System That Only Women Knew How to Write The Writing Systems of the World Explained, from the Latin Alphabet to the Abugidas of India Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/04/11 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |