[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, April 15th, 2025

| Time | Event |

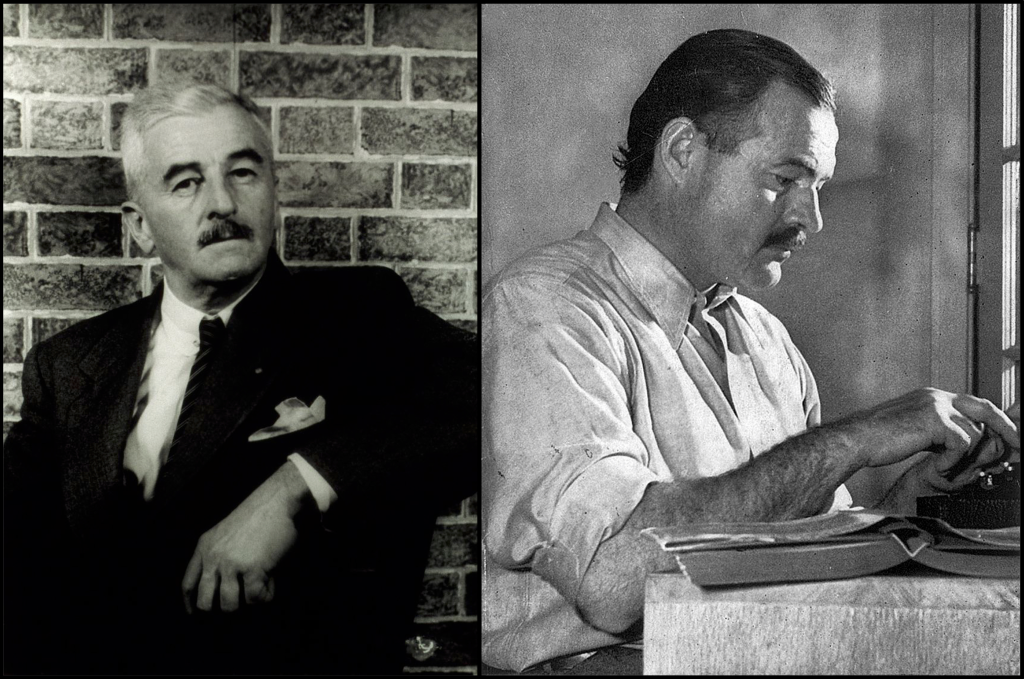

| 8:00a | William Faulkner’s Review of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

In the mid-20th century, the two big dogs in the American literary scene were William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway. Both were internationally revered, both were masters of the novel and the short story, and both won Nobel Prizes. Born in Mississippi, Faulkner wrote allegorical histories of the South in a style that is both elliptical and challenging. His works were marked by uses of stream-of-consciousness and shifting points of view. He also favored titanically long sentences, holding the record for having, according to the Guinness Book of Records, the longest sentence in literature. Open your copy of Absalom! Absalom! to chapter 6 and you’ll find it. Hemingway, on the other hand, famously sandblasted the florid prose of Victorian-era books into short, terse, deceptively simple sentences. His stories were about rootless, damaged, cosmopolitan people in exotic locations like Paris or the Serengeti. If you type in “Faulkner and Hemingway” in your favorite search engine, you’ll likely stumble upon this famous exchange — Faulkner on Hemingway: “He has never been known to use a word that might send a reader to the dictionary.” Hemingway: “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words?” Zing! Faulkner reportedly didn’t mean for the line to come off as an insult but Hemingway took it as one. The incident ended up being the most acrimonious in the two authors’ complicated relationship. While Faulkner and Hemingway never formally met, they were regular correspondents, and each was keenly aware of the other’s talents. And they were competitive with each other, especially Hemingway who was much more insecure than you might surmise from his macho persona. While Hemingway regularly called Faulkner “the best of us all,” marveling at his natural abilities, he also hammered Faulkner for resorting to tricks. As he wrote to Harvey Breit, the famed critic for The New York Times, “If you have to write the longest sentence in the world to give a book distinction, the next thing you should hire Bill Veek [sic] and use midgets.” Faulkner, on his end, was no less competitive. He once told the New York Herald Tribune, “I think he’s the best we’ve got.” On the other hand, he bristled when an editor mentioned getting Hemingway to write the preface for The Portable Faulkner in 1946. “It seems to me in bad taste to ask him to write a preface to my stuff. It’s like asking one race horse in the middle of a race to broadcast a blurb on another horse in the same running field.” When Breit asked Faulkner to write a review of Hemingway’s 1952 novella The Old Man and the Sea, he refused. Yet when a couple months later he got the same request from Washington and Lee University’s literary journal, Shenandoah, Faulkner relented, giving guarded praise to the novel in a one-paragraph-long review. You can read it below.

And you can also watch below a fascinating talk by scholar Joseph Fruscione about how Faulkner and Hemingway competed and influenced each other. He wrote the book, Faulkner and Hemingway: Biography of a Literary Rivalry. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2014. Related Content: The Art of William Faulkner: Drawings from 1916–1925 Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer, 1934 ‘Never Be Afraid’: William Faulkner’s Speech to His Daughter’s Graduating Class in 1951 Seven Tips From William Faulkner on How to Write Fiction Rare 1952 Film: William Faulkner on His Native Soil in Oxford, Mississippi Jonathan Crow is a writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. |

| 9:00a | The Ark Before Noah: Discover the Ancient Flood Myths That Came Before the Bible The Lord said to Noah, there’s going to be a floody, floody; then to get those children out of the muddy, muddy; then to build him an arky, arky. This much we heard while toasting marshmallows around the campfire, at least if we grew up in a certain modern Protestant tradition. As adults, we may or may not believe that there ever lived a man called Noah who built an ark to save all the world’s innocent animal species from a sin-cleansing flood. But unless we’ve taken a deep dive into ancient history, we probably don’t know that this especially famous Bible story wasn’t the first of its particular subgenre. As explained in the Hochelaga video above, there are even older global-deluge tales to be reckoned with. In fact, one such myth appears in the oldest known work of literature in human history, the Epic of Gilgamesh. “In it, the god Ea learns of this divine flood, and secretly warns the humans about this coming disaster,” says Hochelaga creator Tommie Trelawny. Thus informed, the king Utnapishtim builds a giant coracle, a kind of circular boat “used to navigate the rivers of Mesopotamia for centuries.” Like Noah, Utnapishtim brings his family and a host of animals aboard, and after riding out the worst of the storm, finds that his craft has come to rest on a mountaintop. Also like Noah, he then sends birds out to find dry land. But ultimately, “the story takes a strange turn: instead of being pleased, the gods are angry,” though Ea does step in to take responsibility and make sure that Utnapishtim is rewarded. There are other versions with other gods, floods, and ark-builders as well. In the Religion for Breakfast video just above, religious studies scholar Andrew Mark Henry compares the Biblical story of Noah and the Utnapishtim episode of the Epic of Gilgamesh with the “Sumerian flood story” from the second millennium BC and the two-centuries-older “Atrahasis epic.” All of these versions have a good deal in common, not least the executive decision by an exasperated higher being (or beings) to wipe out almost entirely the humanity they themselves created. Ironically, we moderns are likely to have first encountered this tale of godly wrath and subsequent mass destruction in lighthearted, even cheerful presentations. Whether ancient Sumerians also sang about it in youth groups, no clay tablet has yet revealed. Related content: Discover Thomas Jefferson’s Cut-and-Paste Version of the Bible, and Read the Curious Edition Online A Map of All the Countries Mentioned in the Bible: What The Countries Were Called Then, and Now Isaac Asimov’s Guide to the Bible: A Witty, Erudite Atheist’s Guide to the World’s Most Famous Book Did the Tower of Babel Actually Exist?: A Look at the Archaeological Evidence The Epic of Gilgamesh, the Oldest-Known Work of Literature in World History Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/04/15 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |