[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, April 21st, 2025

| Time | Event |

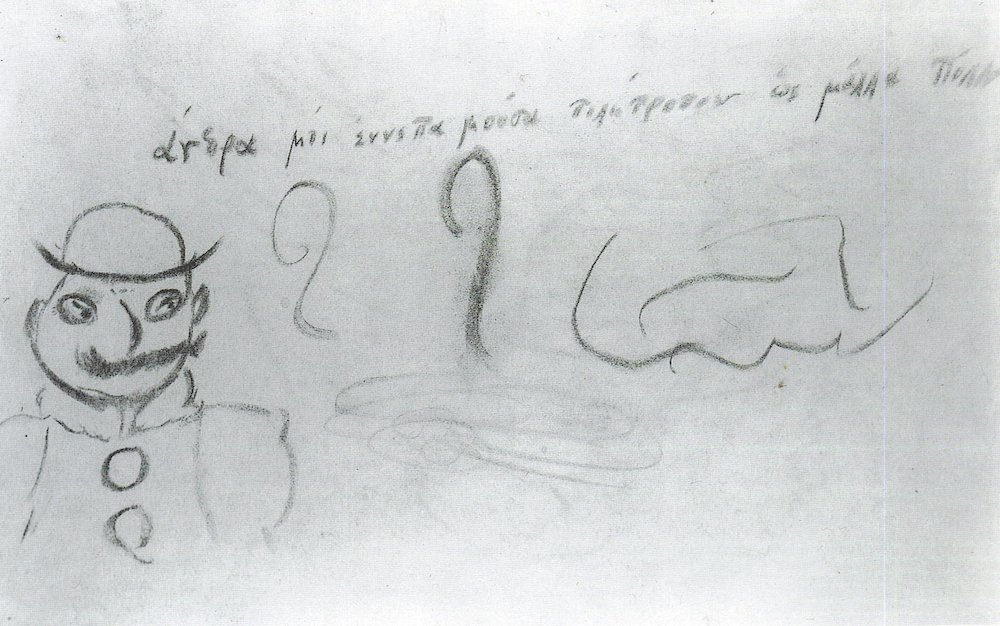

| 8:00a | James Joyce, With His Eyesight Failing, Draws a Sketch of Leopold Bloom (1926)

James Joyce had a terrible time with his eyes. When he was six years old he received his first set of eyeglasses, and, when he was 25, he came down with his first case of iritis, a very painful and potentially blinding inflammation of the colored part of the eye, the iris. A short time later, he named his newborn daughter “Lucia,” after the patron saint of those with eye troubles. For the rest of his life, Joyce had to endure a horrific series of operations and treatments for one or the other of his eyes, including the removal of parts of the iris, a reshaping of the pupil, the application of leeches directly on the eye to remove fluid–even the removal of all of Joyce’s teeth, on the theory that his recurring iritis was connected with the bacterial infection in his teeth, brought on by years of poverty and dental neglect. After his seventh eye operation on December 5, 1925, according to Gordon Bowker in James Joyce: A New Biography, Joyce was “unable to see lights, suffering continual pain from the operation, weeping oceans of tears, highly nervous, and unable to think straight. He was now dependent on kind people to see him across the road and hail taxis for him. All day, he lay on a couch in a state of complete depression, wanting to work but quite unable to do so.” In early 1926, Joyce’s sight was improving a little in one eye. It was about this time (January 1926, according to one source) that Joyce paid a visit to his friend Myron C. Nutting, an American painter who had a studio in the Montparnasse section of Paris. To demonstrate his improving vision, Joyce picked up a thick black pencil and made a few squiggles on a sheet of paper, along with a caricature of a mischievous man in a bowler hat and a wide mustache–Leopold Bloom, the protagonist of Ulysses. Next to Bloom, Joyce wrote in Greek (“with a minor error in spelling and characteristically skewed accents,” according to R. J. Schork in Greek and Hellenic Culture in Joyce) the opening passage of Homer’s Odyssey: “Tell me, muse, of that man of many turns, who wandered far and wide.” NOTE: Joyce’s drawing of Bloom is now in the Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections at Northwestern University. Nutting was a significant source for the biography of Joyce that was written by Richard Ellmann, a professor at Northwestern. According to Scott Krafft, a curator at the library, Ellmann brokered a deal in 1960 for the library to purchase Nutting’s oil paintings of James and Nora Joyce, his pastel drawings of the Joyce children Giorgio and Lucia, along with Joyce’s sketch of Bloom, for a total of $500. The source for the January 1926 date of the Bloom sketch is an article, “James Joyce…a quick sketch” from the July 1976 edition of Footnotes, published by the Northwestern University Library Council. Our thanks to Scott Krafft. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2013. Related Content: James Joyce: An Animated Introduction to His Life and Literary Works What Makes James Joyce’s Ulysses a Masterpiece: Great Books Explained James Joyce’s Crayon Covered Manuscript Pages for Ulysses and Finnegans Wake Read the Original Serialized Edition of James Joyce’s Ulysses (1918) |

| 9:00a | The Extreme Life and Philosophy of Hunter S. Thompson: Gonzo Journalism and the American Condition Hunter S. Thompson has been gone for two decades now. When he went out, as the new Pursuit of Wonder video on his life and work reminds us, he did so in a highly American manner: with a gun, and at the moment of his own choosing. Even his longtime fans who respected something about the agency evident in that choice naturally regretted that he’d made it; many of us have wished aloud that we could read his judgments of the past twenty years’ developments in U.S. politics, culture, and society, which would certainly fit in well enough with the narrative of decline he’d pursued since the late sixties. At the same time, we recognize that Thompson’s manner of living would hardly have allowed him to live into his late eighties (the man himself expressed surprise to have reached his sixties), and that it was inextricable from his manner of writing. Which is not to call it the main ingredient: as generations of imitators have proven, ingestion of controlled substances and a disrespect for traditional narrative structure do not, by themselves, constitute a recipe for the “gonzo journalism” Thompson pioneered. In fact, he had a healthy respect for structure, cultivated through his early career in workaday reportage and a self-imposed training regime that involved re-typing the whole of A Farewell to Arms and The Great Gatsby. Gonzo journalism, according to the narrator of the video, actually has a serious question to ask: “Are not the particular subjective filters by which facts and events are processed and imagined in a moment in history as relevant as the facts themselves in understanding the truth of that moment, or at least a slice of the truth?” Thompson’s most widely read books Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 stand as two attempts at an answer. But from the late seventies onward, as his “lifelong companions of drugs and chaotic behavior nestled closer, the lines between his larger-than-life character in his work, his public persona, and his true self began to blur.” It could be said that Thompson never recovered the deceptive clarity of his Fear and Loathing-era work, though he remained prolific to the end. Indeed, there’s much of value in his last three decades of writing for readers attuned to who he really was. “He was not merely the character he portrayed in his work and public life, but the man who cared enough, and was talented enough, to create this character in order to explore, understand, and represent a very nuanced condition of the world during his time.” It would, perhaps, have been better if he’d been able, at some point, to retire the drugs, the firearms, the sunglasses, and the paranoia and come up with a new persona. What kept him from doing so? Maybe the notion, as articulated by his great inspiration Fitzgerald, that there are no second acts in American lives. Related content: Read 9 Free Articles by Hunter S. Thompson That Span His Gonzo Journalist Career (1965–2005) Hunter S. Thompson, Existentialist Life Coach, Gives Tips for Finding Meaning in Life Read 18 Lost Stories From Hunter S. Thompson’s Forgotten Stint As a Foreign Correspondent Hunter S. Thompson’s Harrowing, Chemical-Filled Daily Routine Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/04/21 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |