[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, May 26th, 2025

| Time | Event |

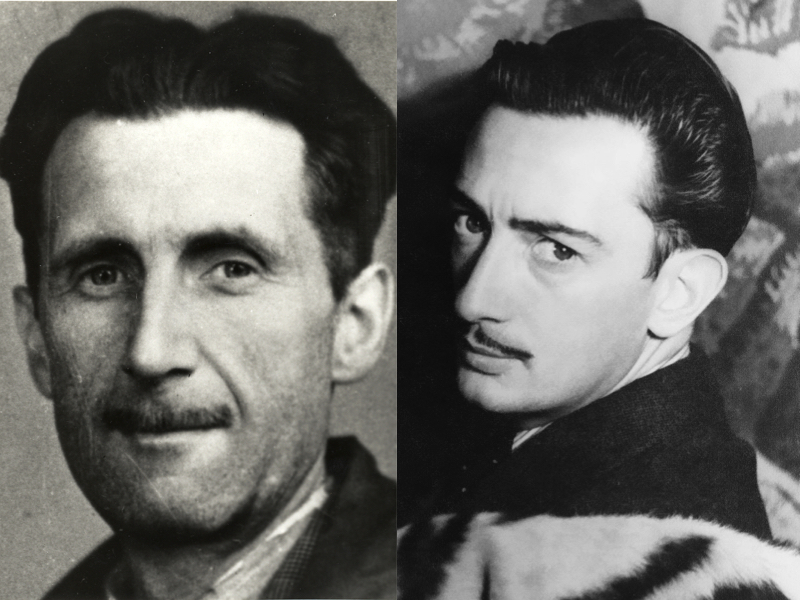

| 8:00a | George Orwell Reviews Salvador Dali’s Autobiography: “Dali is a Good Draughtsman and a Disgusting Human Being” (1944)

Images or Orwell and Dali via Wikimedia Commons Should we hold artists to the same standards of human decency that we expect of everyone else? Should talented people be exempt from ordinary morality? Should artists of questionable character have their work consigned to the trash along with their personal reputations? These questions, for all their timeliness in the present, seemed no less thorny and compelling 81 years ago when George Orwell confronted the strange case of Salvador Dali, an undeniably extraordinary talent, and—Orwell writes in his 1944 essay “Benefit of Clergy”—a “disgusting human being.” The judgment may seem overly harsh except that any honest person would say the same given the episodes Dali describes in his autobiography, which Orwell finds utterly revolting. “If it were possible for a book to give a physical stink off its pages,” he writes, “this one would.” The episodes he refers to include, at six years old, Dali kicking his three-year-old sister in the head, “as though it had been a ball,” the artist writes, then running away “with a ‘delirious joy’ induced by this savage act.” They include throwing a boy from a suspension bridge, and, at 29 years old, trampling a young girl “until they had to tear her, bleeding, out of my reach.” And many more such violent and disturbing descriptions. Dali’s litany of cruelty to humans and animals constitutes what we expect in the early life of serial killers rather than famous artists. Surely he is putting his readers on, wildly exaggerating for the sake of shock value, like the Marquis de Sade’s autobiographical fantasies. Orwell allows as much. Yet which of the stories are true, he writes, “and which are imaginary hardly matters: the point is that this is the kind of thing that Dali would have liked to do.” Moreover, Orwell is as repulsed by Dali’s work as he is by the artist’s character, informed as it is by misogyny, a confessed necrophilia and an obsession with excrement and rotting corpses.

Orwell is unwilling to dismiss the value of Dali’s art, and distances himself from those who would do so on moralistic grounds. “Such people,” he writes, are “unable to admit that what is morally degraded can be aesthetically right,” a “dangerous” position adopted not only by conservatives and religious zealots but by fascists and authoritarians who burn books and lead campaigns against “degenerate” art. “Their impulse is not only to crush every new talent as it appears, but to castrate the past as well.” (“Witness,” he notes, the outcry in America “against Joyce, Proust and Lawrence.”) “In an age like our own,” writes Orwell, in a particularly jarring sentence, “when the artist is an exceptional person, he must be allowed a certain amount of irresponsibility, just as a pregnant woman is.” At the very same time, Orwell argues, to ignore or excuse Dali’s amorality is itself grossly irresponsible and totally inexcusable. Orwell’s is an “understandable” response, writes Jonathan Jones at The Guardian, given that he had fought fascism in Spain and had seen the horror of war, and that Dali, in 1944, “was already flirting with pro-Franco views.” But to fully illustrate his point, Orwell imagines a scenario with a much less controversial figure than Dali: “If Shakespeare returned to the earth to-morrow, and if it were found that his favourite recreation was raping little girls in railway carriages, we should not tell him to go ahead with it on the ground that he might write another King Lear.” Draw your own parallels to more contemporary figures whose criminal, predatory, or violently abusive acts have been ignored for decades for the sake of their art, or whose work has been tossed out with the toxic bathwater of their behavior. Orwell seeks what he calls a “middle position” between moral condemnation and aesthetic license—a “fascinating and laudable” critical threading of the needle, Jones writes, that avoids the extremes of “conservative philistines who condemn the avant garde, and its promoters who indulge everything that someone like Dali does and refuse to see it in a moral or political context.” This ethical critique, writes Charlie Finch at Artnet, attacks the assumption in the art world that an appreciation of artists with Dali’s peculiar tastes “is automatically enlightened, progressive.” Such an attitude extends from the artists themselves to the society that nurtures them, and that “allows us to welcome diamond-mine owners who fund biennales, Gazprom billionaires who purchase diamond skulls, and real-estate moguls who dominate temples of modernism.” Again, you may draw your own comparisons. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2018. Related Content: When The Surrealists Expelled Salvador Dalí for “the Glorification of Hitlerian Fascism” (1934) George Orwell Reviews Mein Kampf: “He Envisages a Horrible Brainless Empire” (1940) How the Nazis Waged War on Modern Art: Inside the “Degenerate Art” Exhibition of 1937 Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| 9:00a | How Bob Dylan Kept Reinventing His Songwriting Process, Breathing New Life Into His Music On his 84th birthday this past Saturday, Bob Dylan played a show. That was in keeping with not only his still-serious touring schedule, but also his apparently irrepressible instinct to work: on music, on writing, on painting, on sculpture. Even his occasional tweeting draws an appreciative audience every time. The Bob Dylan of 2025 is not, of course, the Bob Dylan of 1965, but then, the Bob Dylan of 1965 wasn’t the Bob Dylan of 1964. This constant artistic change is just what his fans appreciate, not that they don’t still put on his early stuff with regularity. In the earliest of that early stuff, as music YouTuber David Hartley explains in the new video above, Dylan “wrote songs by reinventing tradition.” Using nothing but his voice, guitar, and harmonica, the young Dylan “imitated some of the most well-known folk melodies,” placing himself in that long American tradition of borrowing and reinterpretation. But as dramatized in the recent film A Complete Unknown, he soon “went electric,” and with the change in instrumentation came a change in songwriting method: “He would just come up with endless pages of lyrics, something he once called ‘the long piece of vomit.’ ” The advice to “puke it out now and clean it up later” has long been given, in various forms, to aspiring artists everywhere. One aspect worth highlighting about the way Dylan did it was that, despite writing popular songs, he drew a great deal of inspiration from more traditional literature, to the point that his notes hardly appear to contain anything resembling verses or choruses at all. Only in the studio, with a band behind him, could Dylan give these ideas their final musical shape — or rather, their final shape on that particular album, often to be modified endlessly, and sometimes radically, over decades of live performances to come. Hartley tells of more dramatic changes to Dylan’s music and his process of creating. The motorcycle crash, the Basement Tapes, the open E tuning, Blood on the Tracks: all of these now lie half a century or more in the past. To go over all the ways Dylan has approached music since then would require more hours than all but the most rabid enthusiasts (though there are many) would watch. The video does include a 60 Minutes clip from 2004 in which Dylan says that “those early songs were almost magically written,” and that he wouldn’t be able to create them anymore. But then, nor could the Dylan of Highway 61 Revisited have recorded Time Out of Mind, and nor, for that matter, could the Dylan of Time Out of Mind have recorded any of Dylan’s albums from this decade — or those that could, quite possibly, be still to come. Related content: A Massive 55-Hour Chronological Playlist of Bob Dylan Songs: Stream 763 Tracks How Bob Dylan Created a Musical & Literary World All His Own: Four Video Essays Watch Bob Dylan Make His Debut at the Newport Folk Festival in Colorized 1963 Footage Hear Bob Dylan’s Newly Released Nobel Lecture: A Meditation on Music, Literature & Lyrics Bob Dylan Explains Why Music Has Been Getting Worse Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/05/26 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |