[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, May 29th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 6:39a | Leonardo da Vinci’s Elegant Design for a Perpetual Motion Machine

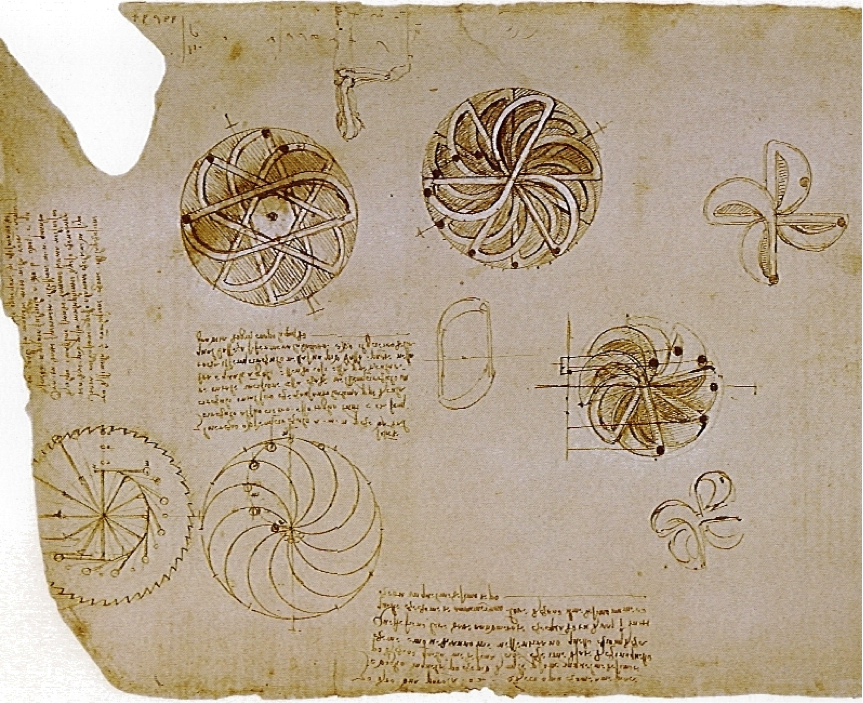

Is perpetual motion possible? In theory… I have no idea…. In practice, so far at least, the answer has been a perpetual no. As Nicholas Barrial writes at Makery, “in order to succeed,” a perpetual motion machine “should be free of friction, run in a vacuum chamber and be totally silent” since “sound equates to energy loss.” Trying to satisfy these conditions in a noisy, entropic physical world may seem like a fool’s errand, akin to turning base metals to gold. Yet the hundreds of scientists and engineers who have tried have been anything but fools. The long list of contenders includes famed 12th-century Indian mathematician Bhāskara II, also-famed 17th-century Irish scientist Robert Boyle, and a certain Italian artist and inventor who needs no introduction. It will come as no surprise to learn that Leonardo da Vinci turned his hand to solving the puzzle of perpetual motion. But it seems, in doing so, he “may have been a dirty, rotten hypocrite,” Ross Pomery jokes at Real Clear Science. Surveying the many failed attempts to make a machine that ran forever, he publicly exclaimed, “Oh, ye seekers after perpetual motion, how many vain chimeras have you pursued? Go and take your place with the alchemists.” In private, however, as Michio Kaku writes in Physics of the Impossible, Leonardo “made ingenious sketches in his notebooks of self-propelling perpetual motion machines, including a centrifugal pump and a chimney jack used to turn a roasting skewer over a fire.” He also drew up plans for a wheel that would theoretically run forever. (Leonardo claimed he tried only to prove it couldn’t be done.) Inspired by a device invented by a contemporary Italian polymath named Mariano di Jacopo, known as Taccola (“the jackdaw”), the artist-engineer refined this previous attempt in his own elegant design.

Leonardo drew several variants of the wheel in his notebooks. Despite the fact that the wheel didn’t work—and that he apparently never thought it would—the design has become, Barrial notes, “THE most popular perpetual motion machine on DIY and 3D printing sites.” (One maker charmingly comments, in frustration, “Perpetual motion doesn’t seem to work, what am I doing wrong?”) The gif at the top, from the British Library, animates one of Leonardo’s many versions of unbalanced wheels. This detailed study can be found in folio 44v of the Codex Arundel, one of several collections of Leonardo’s notebooks that have been digitized and previously made available online. In his book The Innovators Behind Leonardo, Plinio Innocenzi describes these devices, consisting of “12 half-moon-shaped adjacent channels which allow the free movement of 12 small balls as a function of the wheel’s rotation…. At one point during the rotation, an imbalance will be created whereby more balls will find themselves on one side than the other,” creating a force that continues to propel the wheel forward indefinitely. “Leonardo reprimanded that despite the fact that everything might seem to work, ‘you will find the impossibility of motion above believed.’” Leonardo also sketched and described a perpetual motion device using fluid mechanics, inventing the “self-filling flask” over two-hundred years before Robert Boyle tried to make perpetual motion with this method. This design also didn’t work. In reality, there are too many physical forces working against the dream of perpetual motion. Few of the attempts, however, have appeared in as elegant a form as Leonardo’s. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019. Related Content: Leonardo Da Vinci’s To-Do List from 1490: The Plan of a Renaissance Man Leonardo da Vinci Designs the Ideal City: See 3D Models of His Radical Design The Ingenious Inventions of Leonardo da Vinci Recreated with 3D Animation How Leonardo da Vinci Drew an Accurate Satellite Map of an Italian City (1502) Leonardo da Vinci’s Handwritten Resume (Circa 1482) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| 9:00a | Will Machines Ever Truly Think? Richard Feynman Contemplates the Future of Artificial Intelligence (1985) Though its answer has grown more complicated in recent years, the question of whether computers will ever truly think has been around for quite some time. Richard Feynman was being asked about it 40 years ago, as evidenced by the lecture clip above. As his fans would expect, he approaches the matter of artificial intelligence with his characteristic incisiveness and humor — as well as his tendency to re-frame the conversation in his own terms. If the question is whether machines will ever think like human beings, he says no; if the question is whether machines will ever be more intelligent than human beings, well, that depends on how you define intelligence. Even today, it remains quite a tall order for any machine to meet our constant demands, as Feynman articulates, for better-than-human mastery of every conceivable task. And even when their skills do beat mankind’s — as in, say, the field of arithmetic, which computers dominate by their very nature — they don’t use their calculating apparatus in the same way as human beings use their brains. Perhaps, in theory, you could design a computer to add, subtract, multiply, and divide in approximately the same slow, error-prone fashion we tend to do, but why would you want to? Better to concentrate on what humans can do better than machines, such as the kind of pattern recognition required to recognize a single human face in different photographs. Or that was, at any rate, something humans could do better than machines. The tables have turned, thanks to the machine learning technologies that have lately emerged; we’re surely not far from the ability to pull up a portrait, and along with it every other picture of the same person ever uploaded to the internet. The question of whether computers can discover new ideas and relationships by themselves sends Feynman into a disquisition on the very nature of computers, how they do what they do, and how their high-powered inhuman ways, when applied to reality-based problems, can lead to solutions as bizarre as they are effective. “I think that we are getting close to intelligent machines,” he says, “but they’re showing the necessary weaknesses of intelligence.” Arthur C. Clarke said that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic, and perhaps any sufficiently smart machine looks a bit stupid. Related content: The Life & Work of Richard Feynman Explored in a Three-Part Freakonomics Radio Miniseries Stephen Fry Explains Why Artificial Intelligence Has a “70% Risk of Killing Us All” Richard Feynman Creates a Simple Method for Telling Science From Pseudoscience (1966) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/05/29 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |