[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, June 5th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | William Faulkner Resigns From His Post Office Job With a Spectacular Letter (1924)

Working a dull civil service job ill-suited to your talents does not make you a writer, but plenty of famous writers have worked such jobs. Nathaniel Hawthorne worked at a Boston customhouse for a year. His friend Herman Melville put in considerably more time—19 years—as a customs inspector in New York, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. Both Walt Disney and Charles Bukowski worked at the post office, though not together (can you imagine?), and so, for two years, did William Faulkner. After dropping out of the University of Mississippi in 1920, Faulkner became its postmaster two years later, a job he found “tedious, boring, and uninspiring,” writes Mental Floss: “Most of his time as a postmaster was spent playing cards, writing poems, or drinking.” Eudora Welty characterized Faulkner’s tenure as postmaster with the following vignette:

By all accounts, she hardly overstates the case. As author and editor Bill Peschel puts it, Faulkner “opened the post office on days when it suited him, and closed it when it didn’t, usually when he wanted to go hunting or over to the golf course. He would throw away the advertising circulars, university bulletins and other mail he deemed junk.” A student publication from the time proposed a motto for his service: “Never put the mail up on time.” Unsurprisingly, the powers that be eventually decided they’d had enough. In 1924, Faulkner sensed the end coming. But rather than bow out quietly, as perhaps most people would, the future Nobel laureate composed a dramatic and uncharacteristically succinct resignation letter to his superiors:

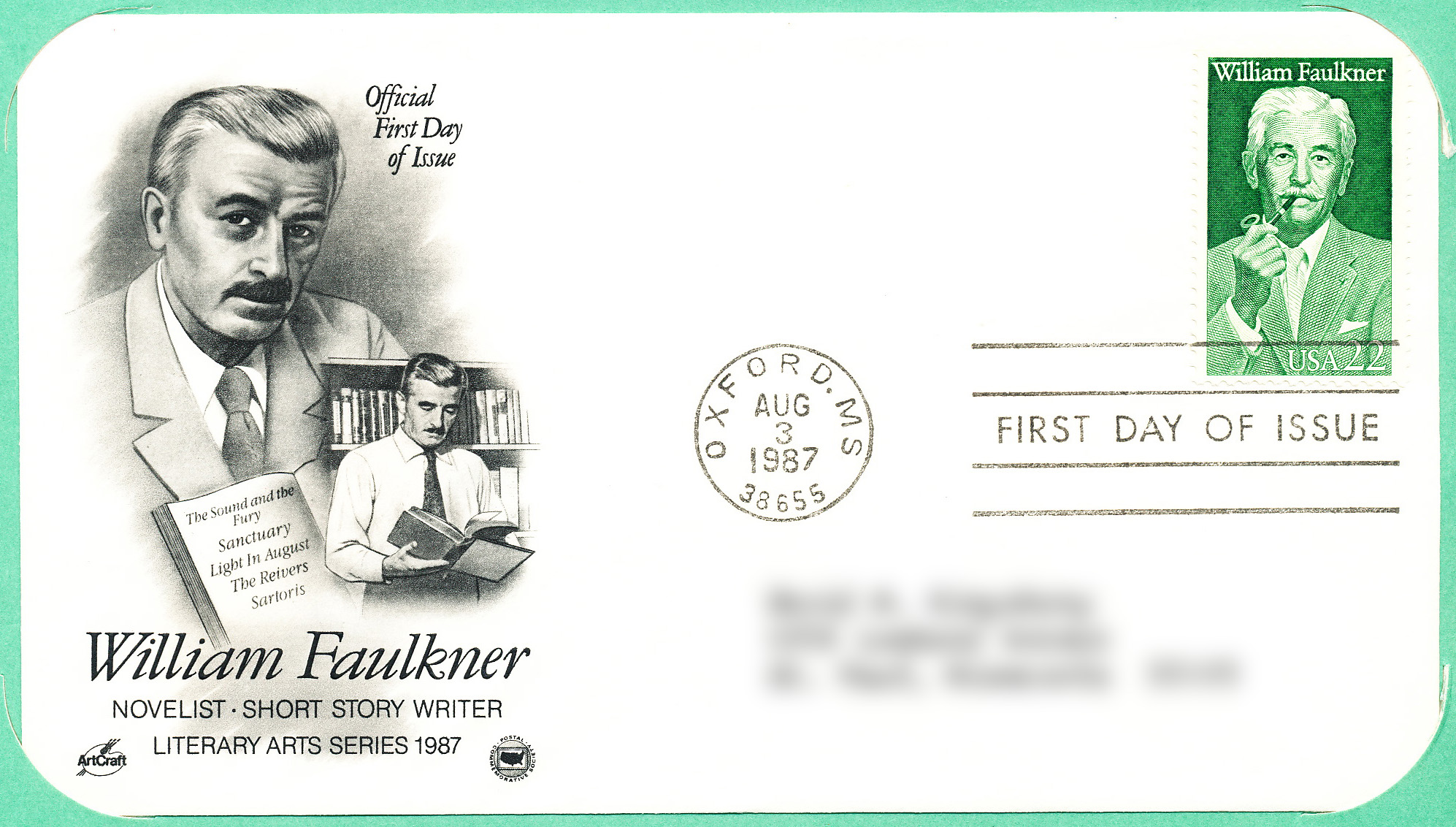

The defiant self-aggrandizement, wounded pride, blame-shifting… maybe it’s these qualities, as well as a notorious tendency to exaggerate and outright lie (about his military service for example) that so qualified him for his late-life career as—in the words of Ole Miss—“Statesman to the World.” Faulkner’s gift for self-fashioning might have suited him well for a career in politics, had he been so inclined. He did, after all, receive a commemorative stamp in 1987 (above) from the very institution he served so poorly. But like Hawthorne, Bukowski, or any number of other writers who’ve held down tedious day jobs, he was compelled to give his life to fiction. In a later retelling of the resignation, Peschel claims, Faulkner would revise his letter “into a more pungent quotation,” unable to resist the urge to invent: “I reckon I’ll be at the beck and call of folks with money all my life, but thank God I won’t ever again have to be at the beck and call of every son of a bitch who’s got two cents to buy a stamp.” Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in Related Content: Seven Tips From William Faulkner on How to Write Fiction William Faulkner’s Review of Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea (1952) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| 9:00a | When the State Department Used Dizzy Gillespie and Jazz to Fight the Cold War (1956) It’s been said that the United States won the Cold War without firing a shot — a statement, as P. J. O’Rourke once wrote, that doubtless surprised veterans of Korea and Vietnam. But it wouldn’t be entirely incorrect to call the long stare-down between the U.S. and the Soviet Union a battle of ideas. Dwight Eisenhower certainly saw it that way, a worldview that inspired the 1956 creation of the President’s Special International Program for Participation in International Affairs, which aimed to use American culture to improve the country’s image around the world. (That same year, Eisenhower also signed off on the construction of the Interstate Highway System, such was the country’s ambition at the time.) For an unambiguously American art form, one could hardly do better than jazz, which also had the advantage of counterbalancing U.S.S.R. propaganda focusing on the U.S.’ troubled race relations. And so the State Department picked a series of “jazz ambassadors” to send on carefully planned world tours, beginning with Dizzy Gillespie and his eighteen-piece interracial band (with the late Quincy Jones in the role of music director). Starting in March of 1956, Gillespie’s ten-week tour featured dates all over Europe, Asia, and South America. These wouldn’t be his last State Department-sponsored tours abroad: in the videos above, you can see a clip from his performance in Germany in 1960. This touring even resulted in live albums like Dizzy in Greece and World Statesman. Other jazz ambassadors would follow: Louis Armstrong (who quit over the high-school integration crisis in Little Rock), Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, and Dave Brubeck (whose dim view of the program inspired the musical The Real Ambassadors). But none went quite so far in pursuing their cultural-political interests as Gillespie, who announced himself as a write-in candidate in the 1964 U.S. presidential election. He promised not only to rename the White House the Blues house, but also to appoint a cabinet including Miles Davis as Director of the CIA, Charles Mingus as Secretary of Peace, Armstrong as Secretary of Agriculture, and Ellington as Secretary of State. This jazzed-up administration was, alas, never to take power, but the music itself has left more of a legacy than any government could. Surely the fact that I write these words in a café in Korea soundtracked entirely by jazz speaks for itself. Related Content: Dizzy Gillespie Worries About Nuclear & Environmental Disaster in Vintage Animated Films Louis Armstrong Plays Historic Cold War Concerts in East Berlin & Budapest (1965) When Louis Armstrong Stopped a Civil War in The Congo (1960) Louis Armstrong Plays Trumpet at the Egyptian Pyramids; Dizzy Gillespie Charms a Snake in Pakistan Dizzy Gillespie Runs for US President, 1964. Promises to Make Miles Davis Head of the CIA How the CIA Secretly Used Jackson Pollock & Other Abstract Expressionists to Fight the Cold War Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/06/05 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |