[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, June 12th, 2025

| Time | Event |

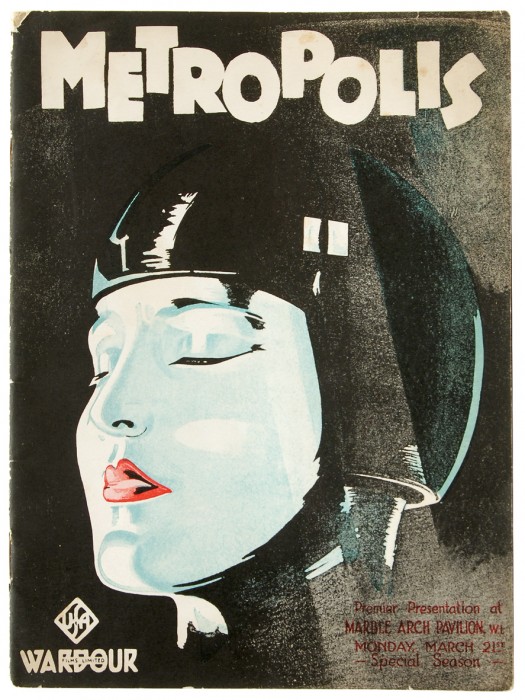

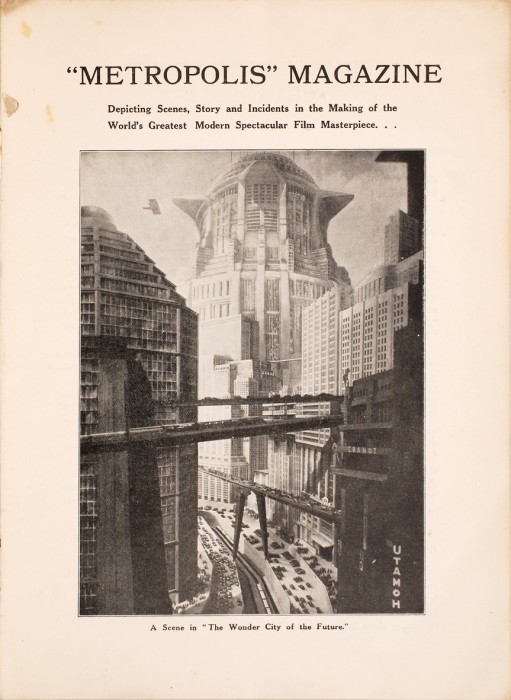

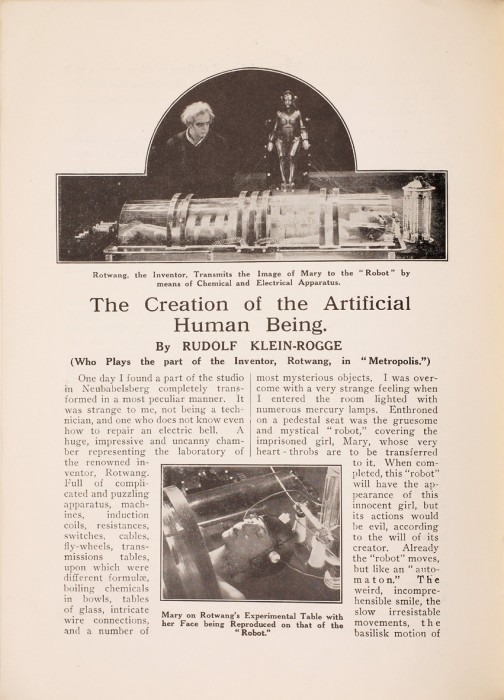

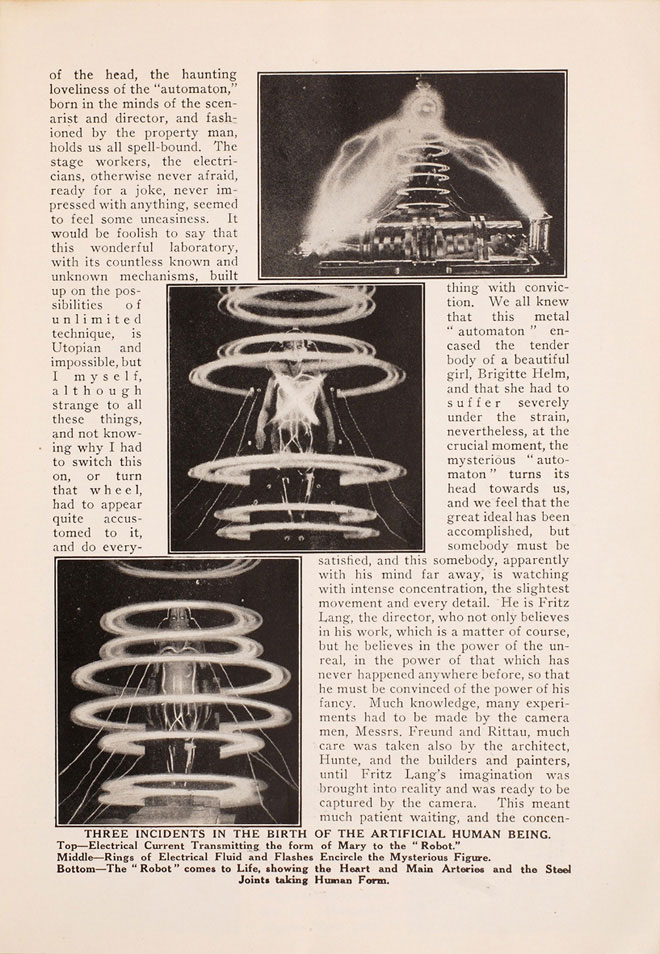

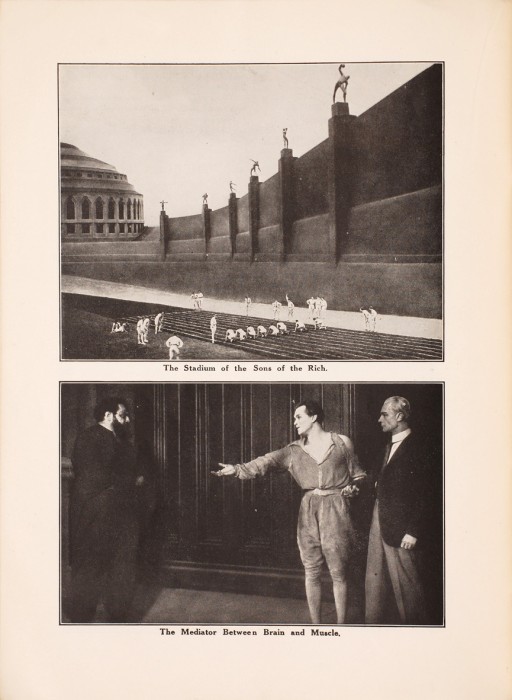

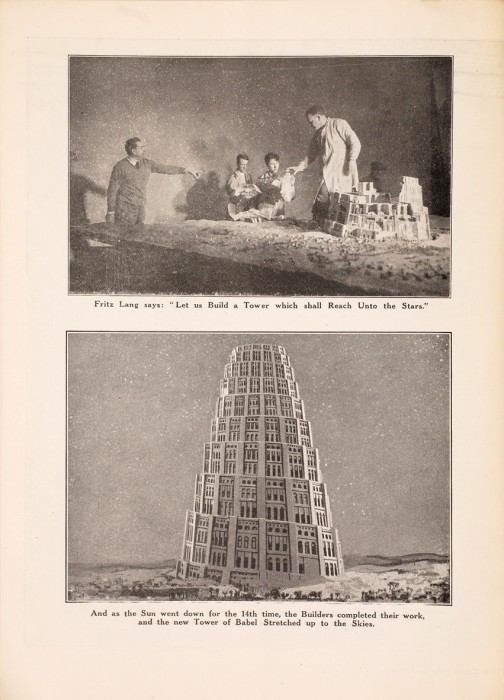

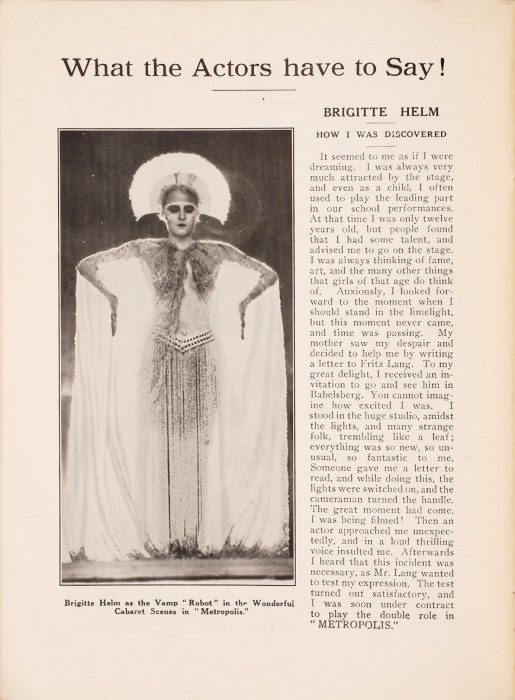

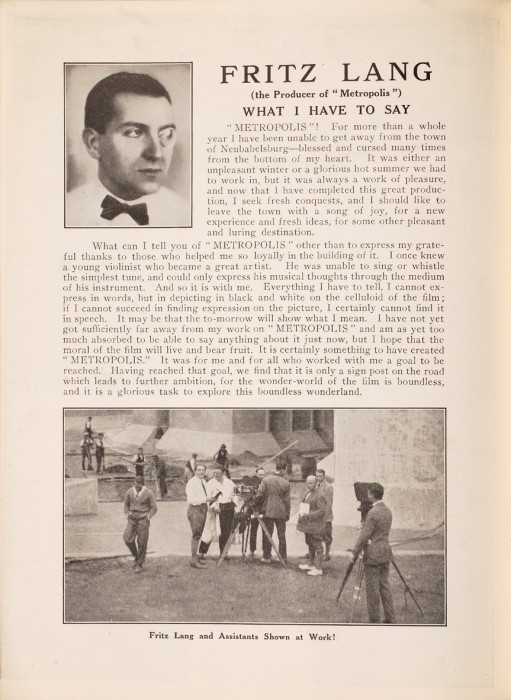

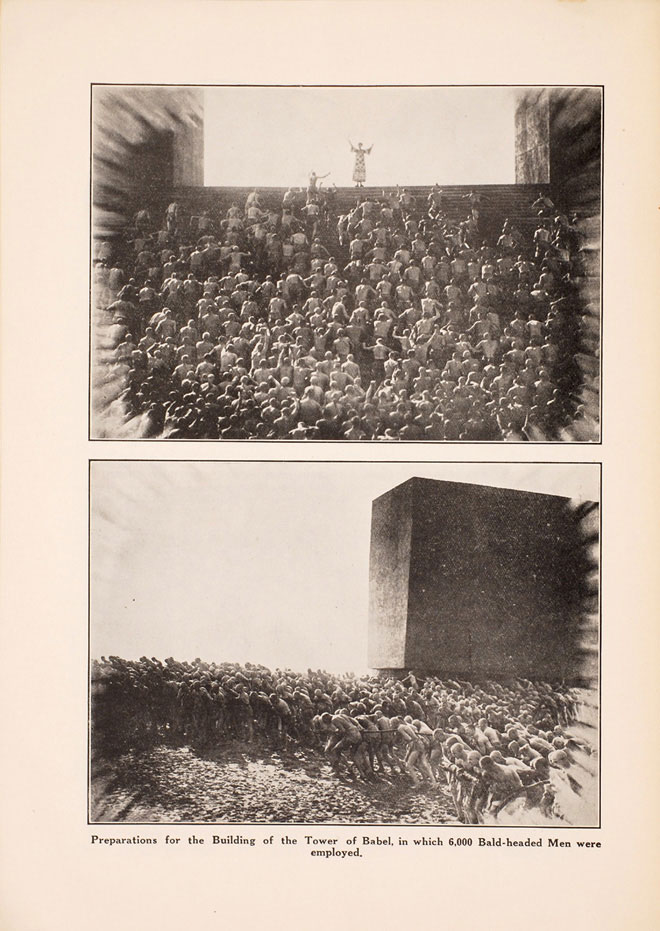

| 8:00a | Read the Original 32-Page Program for Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (1927)  One of the very first feature-length sci-fi films ever made, Fritz Lang’s Metropolis took a daring visual approach for its time, incorporating Bauhaus and Futurist influences in thrillingly designed sets and costumes. Lang’s visual language resonated strongly in later decades. The film’s rather stunning alchemical-electric transference of a woman’s physical traits onto the body of a destructive android—the so-called Maschinenmensch— began a very long trend of female robots in film and television, most of them as dangerous and inscrutable as Lang’s. And yet, for all its many imitators, Metropolis continues to deliver surprises. Here, we bring you a new find: a 32-page program distributed at the film’s 1927 premiere in London and recently re-discovered.  In addition to underwriting almost one hundred years of science fiction film and television tropes, Metropolis has had a very long life in other ways: Inspiring an all-star soundtrack produced by Giorgio Moroder in 1984, with Freddie Mercury, Loverboy, and Adam Ant, and a Kraftwerk album. In 2001, a reconstructed version of Metropolis received a screening at the Berlin Film Festival, and UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register added it to their roster. 2002 saw the release of an exceptional Metropolis-inspired anime with the same title. And in 2010 an almost fully restored print of the long-incomplete film—recut from footage found in Argentina in 2008—appeared, adding a little more sophistication and coherence to the simplistic storyline.  Even at the film’s initial reception, without any missing footage, critics did not warm to its story. For all its intense visual futurism, it has always seemed like a very quaint, naïve tale, struck through with earnest religiosity and inexplicable archaisms. Contemporary reviewers found its narrative of generational and class conflict unconvincing. H.G. Wells—“something of an authority on science fiction”—pronounced it “the silliest film” full of “every possible foolishness, cliché, platitude, and muddlement about mechanical progress and progress in general served up with a sauce of sentimentality that is all its own.” Few were kinder when it came to the story, and despite its overt religious themes, many saw it as Communist propaganda.  Viewed after subsequent events in 20th century Germany, many of the film’s scenes appear “disturbingly prescient,” writes the Unaffiliated Critic, such as the vision of a huge industrial machine as Moloch, in which “bald, underfed humans are led in chains to a furnace.” Lang and his wife Thea von Harbou—who wrote the novel, then screenplay—were of course commenting on industrialization, labor conditions, and poverty in Weimar Germany. Metropolis’s “clear message of classism,” as io9 writes, comes through most clearly in its arresting imagery, like that horrifying, monstrous furnace and the “looming symbol of wealth in the Tower of Babel.”  The visual effects and spectacular set pieces have worked their magic on almost everyone (Wells excluded) who has seen Metropolis. And they remain, for all its silliness, the primary reason for the movie’s cultural prevalence. Wired calls it “probably the most influential sci-fi movie in history,” remarking that “a single movie poster from the original release sold for $690,000 seven years ago, and is expected to fetch even more at an auction later this year.”  We now have another artifact from the movie’s premiere, this 32-page program, appropriately called “Metropolis” Magazine, that offers a rich feast for audiences, and text at times more interesting than the film’s script. (You can view the program in full here.) One imagines had they possessed backlit smart phones, those early moviegoers might have found themselves struggling not to browse their programs while the film screened. But, of course, Metropolis’s visual excesses would hold their attention as they still do ours. Its scenes of a futuristic city have always enthralled viewers, filmmakers, and (most) critics, such that Roger Ebert could write of “vast futuristic cities” as a staple of some of the best science fiction in his review of the 21st-century animated Metropolis—“visions… goofy and yet at the same time exhilarating.”  The program really is an astonishing document, a treasure for fans of the film and for scholars. It’s full of production stills, behind-the-scenes articles and photos, technical minutiae, short columns by the actors, a bio of Thea von Harbou, the “authoress,” excerpts from her novel and screenplay placed side-by-side, and a short article by her. There’s a page called “Figures that Speak” that tallies the production costs and cast and crew numbers (including very crude drawings and numbers of “Negroes” and “Chinese”). Lang himself weighs in, laconically, with a breezy introduction followed by a classic silent-era line: “if I cannot succeed in finding expression on the picture, I certainly cannot find it in speech.” Film history agrees, Lang found his expression “on the picture.”  “Only three surviving copies of this program are known to exist,” writes Wired, and one of them, from which these pages come, has gone on sale at the Peter Harrington rare book shop for 2,750 pounds ($4,244)—which seems rather low, given what an original Metropolis poster went for. But markets are fickle, and whatever its current or future price, ”Metropolis” Magazine is invaluable to cineastes. See all 32 pages of the program at Peter Harrington’s website.  Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016. Related Content: If Fritz Lang’s Iconic Film Metropolis Had a Kraftwerk Soundtrack Behold Beautiful Original Movie Posters for Metropolis from France, Sweden, Germany, Japan & Beyond Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| 9:00a | An Architectural Tour of Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Iconic Desert Home and Studio By some estimations, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West home-studio complex took shape in 1941. But even then, the Arizona Republic presciently noted that “it may be years before it is considered finished.” The Taliesin West you can see in the new Architectural Digest video above is unlikely to change dramatically over the next few generations, but it’s also quite different from what Wright and his apprentices initially designed and built over their first six years of life and work in the Arizona desert. Much of that change has come since Wright himself last saw Taliesin West in 1959, the final year of his life, as the Taliesin Institute’s Jennifer Gray explains while showing the place off. Wright enthusiasts can argue about the degree to which the expansions, modifications, and renovations made by the master’s disciples and others are in keeping with his vision. But in a sense, ongoing growth and metamorphosis (as well as damage and regrowth, resulting from the occasional fire) suits a work of architecture made to look and feel as if it had emerged organically from the natural landscape. Arguably, Taliesin West even exhibits a kind of purity not found in other, more famous Wright buildings, created as it was without a client, and thus without a client’s demands and deadlines — not to mention with the benefit of apprentice labor. Like Wright’s original Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin, Taliesin West was a home, a studio, and most importantly, an educational institution. Wright and his students spent the winters there every year from 1935 on, though it was a completely undeveloped site at first. Just getting there necessitated a vehicular pilgrimage, a great American road trip avant la lettre — and indeed, avant l’autoroute. While the Wrights stayed at an inn, the apprentices camped out on-site, living a hardscrabble but highly educational existence, devoted as it was to building straight from plans that their teacher could have drawn up the day before. Even after Taliesin West was basically built, then hooked up to such luxuries as plumbing and electricity, communal rigors of life there weren’t for every student. Yet it did have its pleasures: it’s not every architecture school, after all, that has its own cabaret. Related content: Take 360° Virtual Tours of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architectural Masterpieces, Taliesin & Taliesin West A Virtual Tour of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Lost Japanese Masterpiece, the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo Inside the Beautiful Home Frank Lloyd Wright Designed for His Son (1952) What Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unusual Windows Tell Us About His Architectural Genius How Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architecture Evolved Over 70 Years and Changed America Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/06/12 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |