[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, June 19th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Hear the Letter of Gratitude That Albert Camus Wrote to His Teacher After Winning the Nobel Prize, as Read by Footballer Ian Wright When Albert Camus won the Nobel Prize, he wrote a letter to one of his old schoolteachers. “I let the commotion around me these days subside a bit before speaking to you from the bottom of my heart,” the letter begins. “I have just been given far too great an honor, one I neither sought nor solicited. But when I heard the news, my first thought, after my mother, was of you.” For it was from this teacher, a certain Louis Germain, that the young, fatherless Camus received the guidance he needed. “Without you, without the affectionate hand you extended to the small poor child that I was, without your teaching and example, none of all this would have happened.” Camus ends the letter by assuring Monsieur Germain that “your efforts, your work, and the generous heart you put into it still live in one of your little schoolboys who, despite the years, has never stopped being your grateful pupil.” In response, Germain recalls his memories of Camus as an unaffected, optimistic pupil. “I think I well know the nice little fellow you were, and very often the child contains the seed of the man he will become,” he writes. Whatever the process of intellectual and artistic evolution over the 30 years or so between leaving the classroom and winning the Nobel, “it gives me very great satisfaction to see that your fame has not gone to your head. You have remained Camus: bravo.” It isn’t hard to understand why Camus’ letter to his teacher would resonate with the footballer Ian Wright, who reads it aloud in the Letters Live video at the top of the post. A 2005 documentary on his life and career produced the early viral video above, a clip capturing the moment of Wright’s unexpected reunion with his own academic father figure, Sydney Pigden. Coming face to face with his old mentor, who he’d assumed had died, Wright instinctively removes his cap and addresses him as “Mr. Pigden.” In that moment, the student-teacher relationship resumes: “I’m so glad you’ve done so well with yourself,” says Pigden, a sentiment not dissimilar to the one Monsieur Germain expressed to Camus. Most of us, no matter how long we’ve been out of school, have a teacher we hope to do proud; some of us, whether we know it or not, have been that teacher. Related Content: Benedict Cumberbatch Reads Albert Camus’ Touching Thank You Letter to His Elementary School Teacher Hear Albert Camus Deliver His Nobel Prize Acceptance Speech (1957) See Albert Camus’ Historic Lecture, “The Human Crisis,” Performed by Actor Viggo Mortensen Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Short, Strange & Brutal Stint as an Elementary School Teacher Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

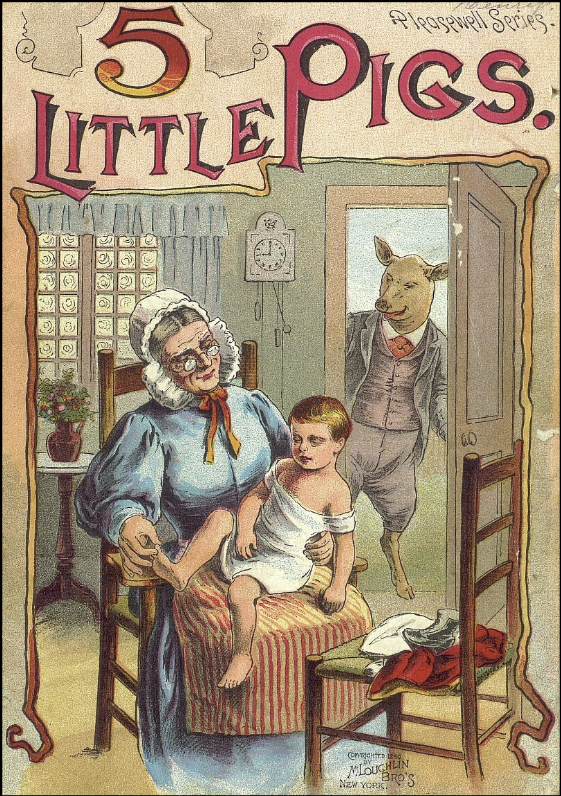

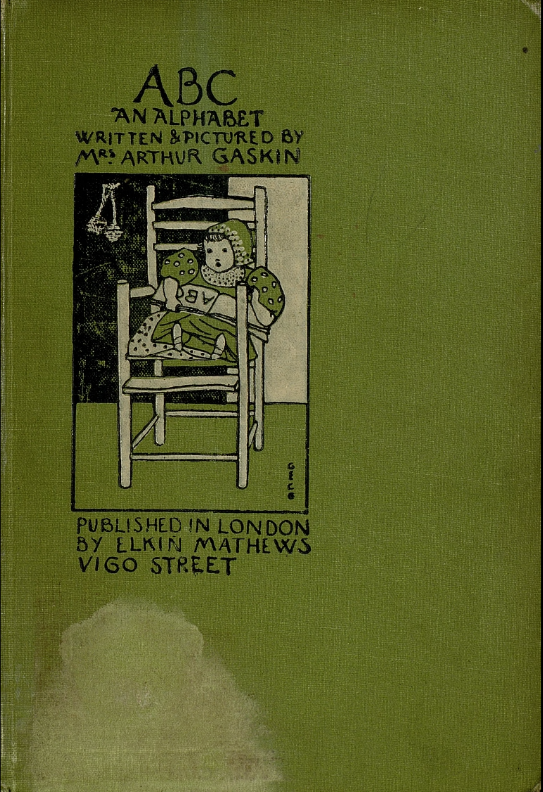

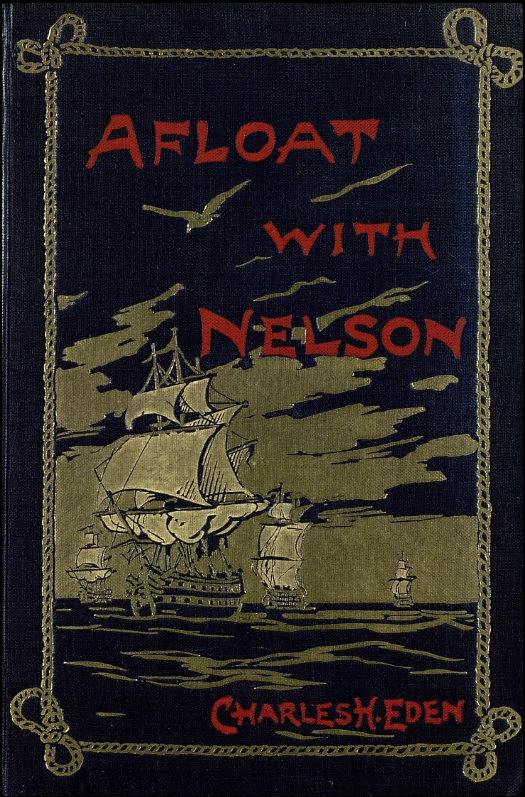

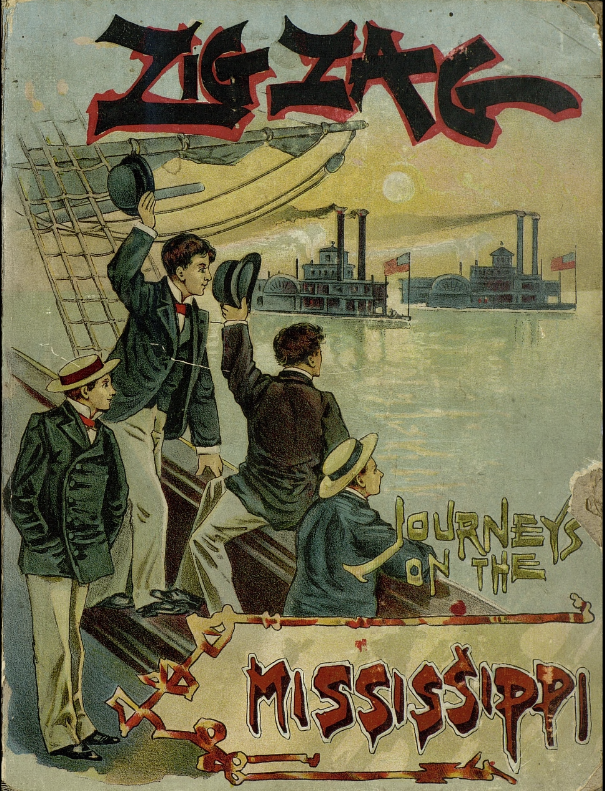

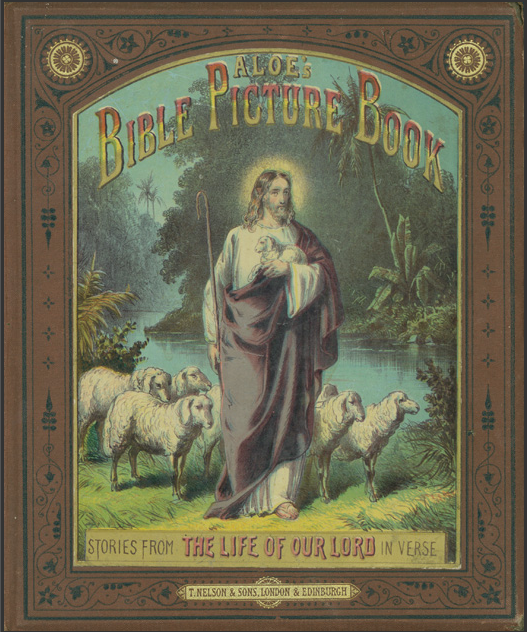

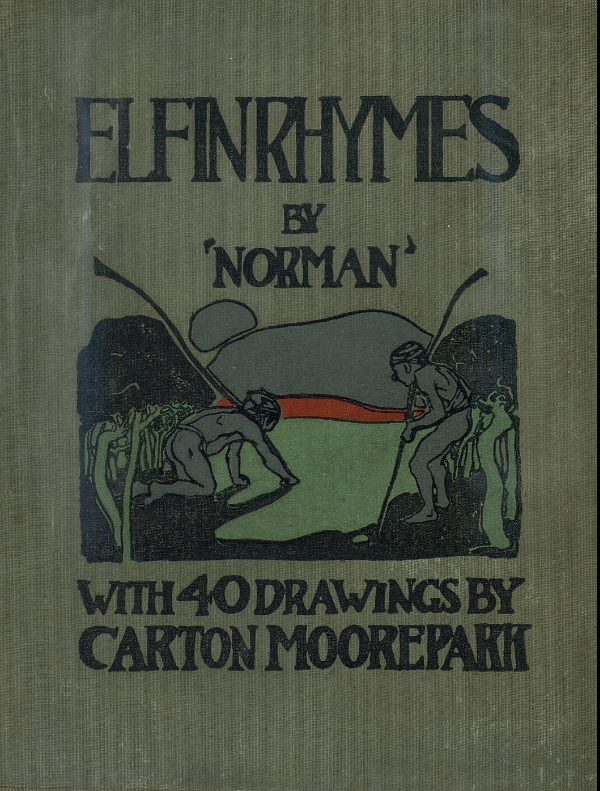

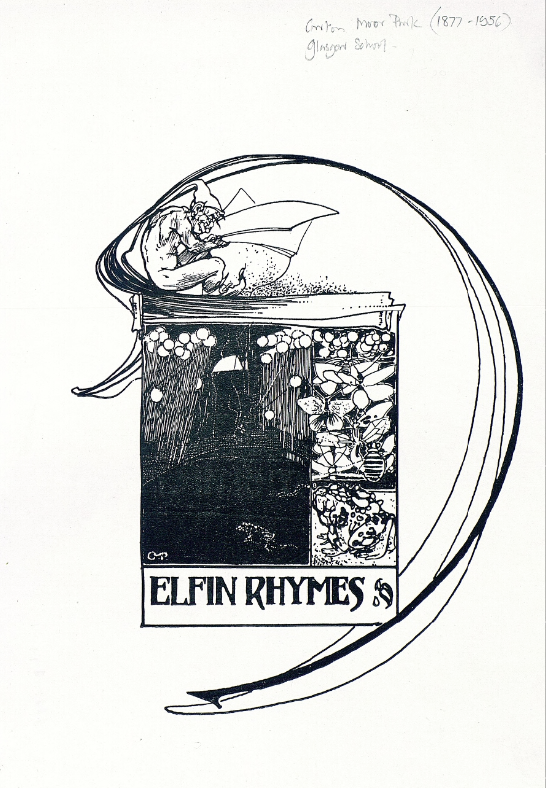

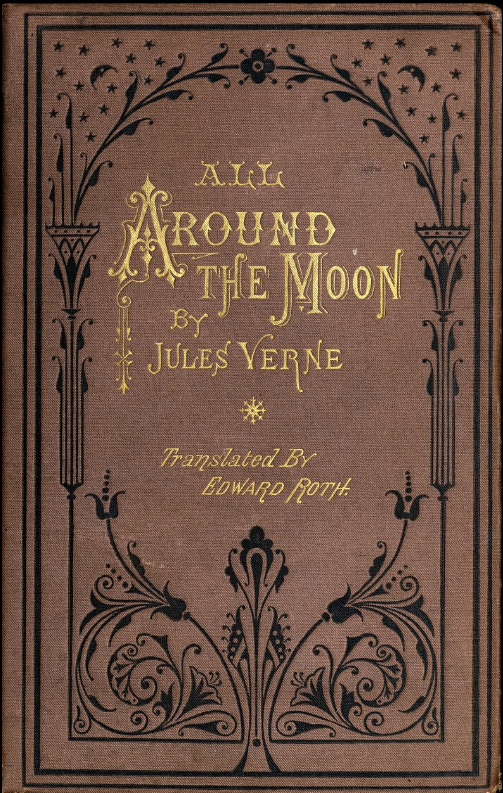

| 9:00a | Enter an Archive of 10,000+ Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized & Free to Read Online  We can learn much about how a historical period viewed the abilities of its children by studying its children’s literature. Occupying a space somewhere between the purely didactic and the nonsensical, most children’s books published in the past few hundred years have attempted to find a line between the two poles, seeking a balance between entertainment and instruction. However, that line seems to move closer to one pole or another depending on the prevailing cultural sentiments of the time. And the very fact that children’s books were hardly published at all before the early 18th century tells us a lot about when and how modern ideas of childhood as a separate category of existence began.  “By the end of the 18th century,” writes Newcastle University professor M.O. Grenby, “children’s literature was a flourishing, separate and secure part of the publishing industry in Britain.” The trend accelerated rapidly and has never ceased—children’s and young adult books now drive sales in publishing (with 80% of YA books bought by grown-ups for themselves). Grenby notes that “the reasons for this sudden rise of children’s literature” and its rapid expansion into a booming market by the early 1800s “have never been fully explained.” We are free to speculate about the social and pedagogical winds that pushed this historical change.  Or we might do so, at least, by examining the children’s literature of the Victorian era, perhaps the most innovative and diverse period for children’s literature thus far by the standards of the time. And we can do so most thoroughly by surveying the thousands of mid- to late 19th century titles at the University of Florida’s Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature. Their digitized collection currently holds over 10,000 books free to read online from cover to cover, allowing you to get a sense of what adults in Britain and the U.S. wanted children to know and believe.  Several genres flourished at the time: religious instruction, naturally, but also language and spelling books, fairy tales, codes of conduct, and, especially, adventure stories—pre-Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew examples of what we would call young adult fiction, these published principally for boys. Adventure stories offered a (very colonialist) view of the wide world; in series like the Boston-published Zig Zag and English books like Afloat with Nelson, both from the 1890s, fact mingled with fiction, natural history and science with battle and travel accounts. But there is another distinctive strain in the children’s literature of the time, one which to us—but not necessarily to the Victorians—would seem contrary to the imperialist young adult novel.  For most Victorian students and readers, poetry was a daily part of life, and it was a central instructional and storytelling form in children’s lit. The A.L.O.E.’s Bible Picture Book from 1871, above, presents “Stories from the Life of Our Lord in Verse,” written “simply for the Lord’s lambs, rhymes more readily than prose attracting the attention of children, and fastening themselves on their memories.” Children and adults regularly memorized poetry, after all. Yet after the explosion in children’s publishing the former readers were often given inferior examples of it. The author of the Bible Picture Book admits as much, begging the indulgence of older readers in the preface for “defects in my work,” given that “the verses were made for the pictures, not the pictures for the verses.”  This is not an author, or perhaps a type of literature, one might suspect, that thinks highly of children’s aesthetic sensibilities. We find precisely the opposite to be the case in the wonderful Elfin Rhymes from 1900, written by the mysterious “Norman” with “40 drawings by Carton Moorepark.” Whoever “Norman” may be (or why his one-word name appears in quotation marks), he gives his readers poems that might be mistaken at first glance for unpublished Christina Rossetti verses; and Mr. Moorepark’s illustrations rival those of the finest book illustrators of the time, presaging the high quality of Caldecott Medal-winning books of later decades. Elfin Rhymes seems like a rare oddity, likely published in a small print run; the care and attention of its layout and design shows a very high opinion of its readers’ imaginative capabilities.  This title is representative of an emerging genre of late Victorian children’s literature, which still tended on the whole, as it does now, to fall into the trite and formulaic. Elfin Rhymes sits astride the fantasy boom at the turn of the century, heralded by hugely popular books like Frank L. Baum’s Wizard of Oz series and J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. These, the Harry Potters of their day, made millions of young people passionate readers of modern fairy tales, representing a slide even further away from the once quite narrow, “remorselessly instructional… or deeply pious” categories available in early writing for children, as Grenby points out.  Where the boundaries for kids’ literature had once been narrowly fixed by Latin grammar books and Pilgrim’s Progress, by the end of the 19th century, the influence of science fiction like Jules Verne’s, and of popular supernatural tales and poems, prepared the ground for comic books, YA dystopias, magician fiction, and dozens of other children’s literature genres we now take for granted, or—in increasingly large numbers—we buy to read for ourselves. Enter the Baldwin Library of Historical Children’s Literature here, where you can browse several categories, search for subjects, authors, titles, etc, see full-screen, zoomable images of book covers, download XML versions, and read all of the over 10,000+ books in the collection with comfortable reader views. Note: This is an updated version of a post that originally appeared on our site in 2016. Related Content: The First Children’s Picture Book, 1658’s Orbis Sensualium Pictus Hayao Miyazaki Selects His 50 Favorite Children’s Books The 100 Greatest Children’s Books of All Time, According to 177 Books Experts from 56 Countries A Digital Archive of 1,800+ Children’s Books from UCLA Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| << Previous Day |

2025/06/19 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |