[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Friday, June 20th, 2025

| Time | Event |

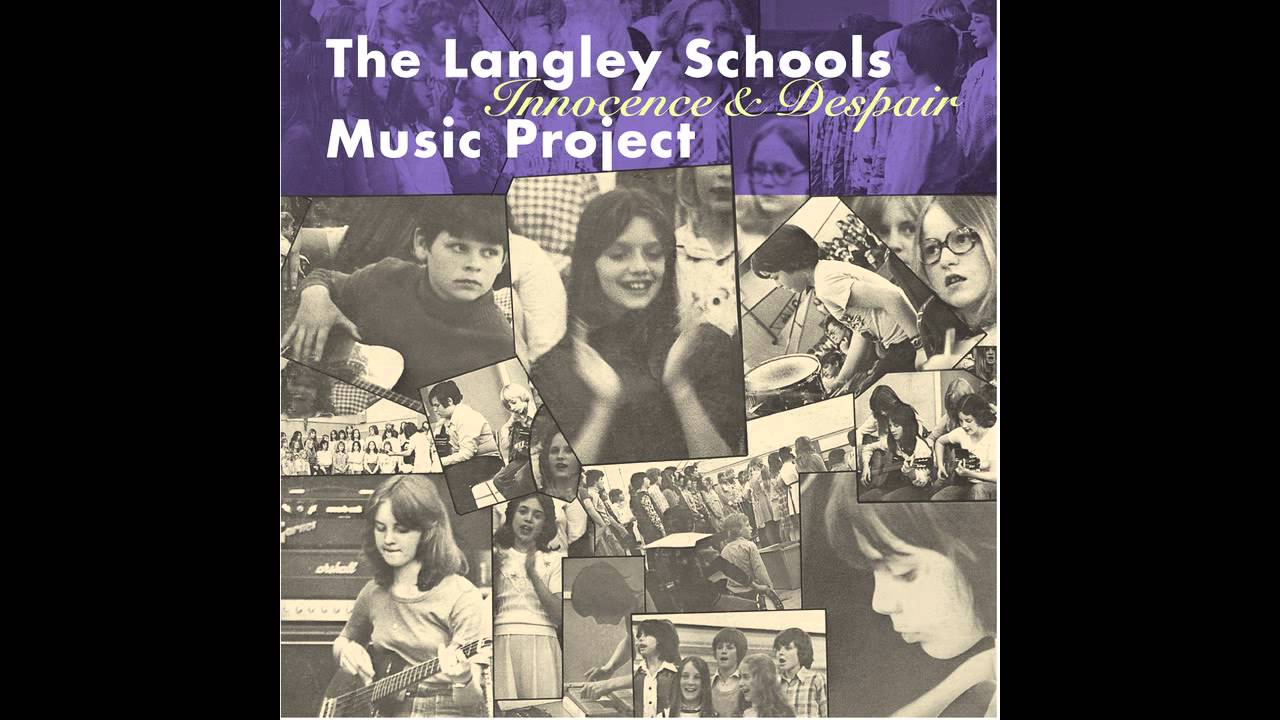

| 8:00a | Elementary School Kids Sing David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” & Other Rock Hits: A Cult Classic Recorded in 1976 In 1976 and 1977 an inspired music teacher in the small school district of Langley Township, British Columbia, a suburb of Vancouver, recorded his elementary school students singing popular songs in a school gym. Two vinyl records were produced over the two years, and families were invited to pay $7 for a copy. The recordings were largely forgotten — just another personal memento stored away in a few homes in Western Canada — until a record collector stumbled across a copy in a thrift store in 2000. Enthralled by what he heard, the collector sent a sample to a disc jockey at WFMU, an eclectic, listener-supported radio station in New Jersey. The station began playing some of the songs over the airwaves. Listeners were touched by the haunting, ethereal quality of the performances. In 2001, a small record company released a compilation called The Langley Township Music Project: Innocence & Despair. The record became an underground hit. The Washington Post called it “an album that seems to capture nothing less than the sound of falling in love with music.” Spin said the album “seems to sum up all the reasons music is holy.” And Dwight Gamer of The New York Times wrote that the music was “magic: a kind of celestial pep rally.” Listeners were moved by the ingenuousness of the young voices, the strange authenticity of performances by children too young to understand all of the adult themes in the lyrics. As Hans Fenger, the music teacher who made the recordings, writes in the liner notes: The kids had a grasp of what they liked: emotion, drama, and making music as a group. Whether the results were good, bad, in tune or out was no big deal — they had élan. This was not the way music was traditionally taught. But then I never liked conventional “children’s music,” which is condescending and ignores the reality of children’s lives, which can be dark and scary. These children hated “cute.” They cherished songs that evoked loneliness and sadness. You can learn the story of Fenger’s extraordinary music project in the 2002 VH1 documentary above, which includes interviews and a reunion with some of the students. And listen below for a few samples of that touching quality of loneliness and sadness Fenger and others have been talking about. David Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’: One of the most widely praised songs from Innocence & Despair is the 1976 recording of David Bowie’s “Space Oddity.” In a 2001 interview with Mike Appelstein for Scram magazine, Fenger explained the sound effects in the recording. “When I first taught ‘Space Oddity,’ ” he said, “the first part I taught after the song was the kids counting down. They loved that: they’d go ‘TEN!’ They couldn’t say it loud enough; the countdown in the song was the big winner. But as soon as they got to zero, nothing happened. So I brought this old steel guitar. Well, one of the little guys whose name I’ve forgot, I put him on this thing and said, ‘Now listen, when they get to zero, you’re the rocket. So make a lot of noise on this. He’s fooling around with this steel guitar, and I didn’t even think of this, but he intuitively took out a Coke bottle from his lunch and started doing this (imitates a bottle running up and down the fretboard). I just cranked up the volume and turned down the master volume so it was really distorted. And that was the ‘Space Oddity’ sound effect.” The Beach Boys’ ‘In My Room’: The children recorded “In My Room” by the Beach Boys in 1977. Fenger told Appelstein it was the ultimate children’s song. “It’s the perfect introspective song for a nine-year-old,” he said, “just as ‘Dust in the Wind’ is the perfect philosophy song for a nine-year-old. Adults may think it’s dumb, but for a child, it’s a very heavy, profound thought. To think that there is nothing, and it’s expressed in such a simple way.” The Eagles’ ‘Desperado’: Several of the recordings feature soloists. A young girl named Sheila Behman sang the Eagles’ “Desperado” in 1977. “With ‘Desperado,’ ” said Fenger, “you can see it as a cowboy romantic story, but that’s not the way Sheila heard it. She couldn’t articulate metaphorically what the song was about, but in that sense, I think it was purer because it was unaffected. It’s not as if the kids were trying to be somebody else. They were just trying to be who they were, and they’re doing this music and falling in love with it.” Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2013. Related Content David Bowie Urges Kids to READ in a 1987 Poster Sponsored by the American Library Association David Bowie Songs Reimagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers: Space Oddity, Heroes, Life on Mars & More When David Bowie Launched His Own Internet Service Provider: The Rise and Fall of BowieNet (1998) How David Bowie Used William S. Burroughs’ Cut-Up Method to Write His Unforgettable Lyrics |

| 9:00a | When the Dutch Tried to Live in Concrete Spheres: An Introduction to the Bolwoningen in the Netherlands In the decades after the Second World War, many countries faced the challenge of rebuilding their housing and infrastructure while also having to accommodate a fast-arriving baby boom. The government of the Netherlands got more creative than most, putting money toward experimental housing projects starting in the late nineteen-sixties. Hoping to happen upon the next revolutionary form of dwelling, it ended up funding designs that, for the most part, strayed none too far from established patterns. Still, there were genuine outliers: by far the most daring proposal came from artist and sculptor Dries Kreijkamp: to build a whole neighborhood out of Bolwoningen, or “ball houses.” The idea may bring to mind Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes, which enjoyed a degree of utopian vogue in the nineteen-sixties and seventies. Like Fuller and most other visionaries, Kreijkamp labored under a certain monomania. His had to do with globes, “the most organic and natural shape possible. After all, roundness is everywhere: we live on a globe, and we’re born from a globe. The globe combines the biggest possible volume with the smallest possible surface area, so you need minimum material for it.” The 50 Bolwoningen built in ‘s‑Hertogenbosch, better known as Den Bosch, were quickly fabricated on-site out of glass fiber reinforced concrete. It wasn’t the polyester Kreijkamp had at first specified, but then, polyester wouldn’t have lasted 40 years. Since they were put up in 1984, the Bolwoningen have been continuously inhabited. In the video at the top of the post, Youtuber Tom Scott pays a visit to one of them, whose occupant seems reasonably satisfied. (It seems they’re “cozy” in the wintertime.) Like geodesic domes, their round walls make it difficult to use their theoretically generous interior space efficiently, at least without commissioning custom-made furniture; leaking windows are also a perennial problem. While each Bolwoning can comfortably house one or even two simple-living people, only the most utopia-minded would attempt to raise a family in one of them. As with other round or circular home designs, expansion would be physically impractical even if it were legally possible. Used as social housing by the local government, the Bolwoningen now enjoy a protected historic status. (As well they might, given their connection with the art and industry of Dutch glassblowing: it was while working in a glass factory that Kreijkamp first began proselytizing for spheres.) And unlike most aesthetically radical housing developments, they haven’t gone to seed, but rather received the necessary maintenance over the decades. The result is an appealing neighborhood for those whose lifestyles are suited to its unusual structures and its contained bucolic setting, of which you can get an idea in the walking video tour just above. By the time Kreijkamp died in 2014, he perhaps felt a certain degree of regret that mass-produced globular homes didn’t prove to be the next big thing. But he did live to see the emergence of the “tiny house” movement, which should retroactively adopt him as one of its leading lights. Related content: The Life & Times of Buckminster Fuller’s Geodesic Dome: A Documentary Goodbye to the Nakagin Capsule Tower, Tokyo’s Strangest and Most Utopian Apartment Building The Utopian, Socialist Designs of Soviet Cities Watch an Animated Buckminster Fuller Tell Studs Terkel All About “the Geodesic Life” Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/06/20 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |