[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, July 17th, 2025

| Time | Event |

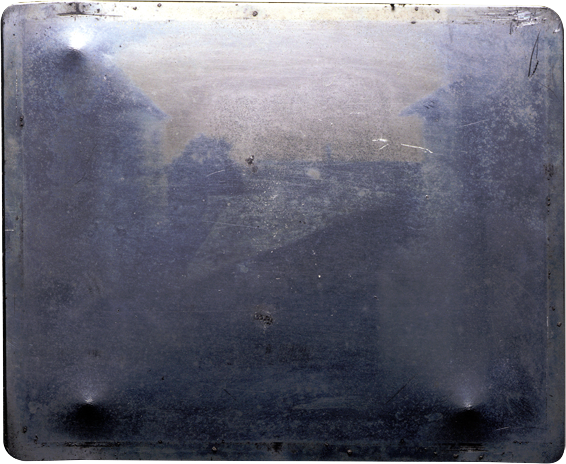

| 8:00a | The First Photograph Ever Taken (1826)

In histories of early photography, Louis Daguerre faithfully appears as one of the fathers of the medium. His patented process, the daguerreotype, in wide use for nearly twenty years in the early 19th century, produced so many of the images we associate with the period, including famous photographs of Abraham Lincoln, Edgar Allan Poe, Emily Dickinson, and John Brown. But had things gone differently, we might know better the harder-to-pronounce name of his onetime partner Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, who produced the first known photograph ever, taken in 1826. Something of a gentleman inventor, Niépce (below) began experimenting with lithography and with that ancient device, the camera obscura, in 1816. Eventually, after much trial and error, Niépce developed his own photographic process, which he called “heliography.” He began by mixing chemicals on a flat pewter plate, then placing it inside a camera. After exposing the plate to light for eight hours, the inventor then washed and dried it. What remained was the image we see above, taken, as Niépce wrote, from “the room where I work” on his country estate and now housed at the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center.

At the Ransom Center website, you can see a short video describing Niépce’s house and showing how scholars recreated the vantage point from which he took the picture. Another video offers insight into the process Niépce invented to create his “heliograph.” In 1827, Niépce traveled to England to visit his brother. While there, with the assistance of English botanist Francis Bauer, he presented a paper on his new invention to the Royal Society. His findings were rejected, however, because he opted not to fully reveal the details, hoping to make economic gains with a proprietary method. Niépce left the pewter image with Bauer and returned to France, where he shortly after agreed to a ten-year partnership with Daguerre in 1829. Sadly for Niépce, his heliograph would not produce the financial or technological success he envisioned, and he died just four years later in 1833. Daguerre, of course, went on to develop his famous process in 1839 and passed into history, but we should remember Niépce’s efforts, and marvel at what he was able to achieve on his own with limited materials and no training or precedent. Daguerre may receive much of the credit, but it was the “scientifically-minded gentleman” Niépce and his heliography that led—writes the Ransom Center’s Head of Photographic Conservation Barbara Brown—to “the invention of the new medium.”

Niépce’s pewter plate image was re-discovered in 1952 by Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, who published an article on the find in The Photographic Journal. Thereafter, the Gernsheims had the Eastman Kodak Company create the reproduction above. This image’s “pointillistic effect,” writes Brown, “is due to the reproduction process,” and the image “was touched up with watercolors by [Helmut] Gernsheim himself in order to bring it as close as possible to his approximation of how he felt the original should appear in reproduction.” Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015. Related Content: The First “Selfie” In History Taken by Robert Cornelius, a Philadelphia Chemist, in 1839 The First Known Photograph of People Having a Beer (1843) The Oldest Known Photographs of Rome (1841–1871) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| 9:00a | How Jackie Chan Filmed the Best Fight Scene in Cinema History Though now in his seventies, Jackie Chan continues to appear on the big screen with regularity. For most world-famous actors, that’s hardly notable, but it’s not as if Sir John Gielgud, say, had spent decades filming scenes of hand-to-hand combat and sustaining severe injuries in the performance of elaborate stunts. Viewers of New Police Story 2 and Rush Hour 4, to name just two upcoming franchise projects, will surely delight, as always, in Chan’s very screen presence. But it goes without saying that he won’t be attempting anything like what he did in his breakout Hong Kong films of the seventies and eighties, which required a singular dedication both physical and cinematic. There are also fans who argue that Chan reached his peak in the nineties, most of whom would adduce the climactic fight scene above from Drunken Master II. Made in 1994, when Chan was 40 years old, it came as the ostensible sequel to Drunken Master, from 1978, in which Chan’s portrayal of the titular Qing dynasty folk hero launched him to stardom in Asia. Released in the U.S. as The Legend of Drunken Master in 2000 — after Chan had finally made it stateside with Rumble in the Bronx and the first Rush Hour — Drunken Master II met with critical astonishment. “It involves some of the most intricate, difficult and joyfully executed action sequences I have ever seen,” wrote Roger Ebert. His judgment of the final, steel-forge-set showdown: “It may not be possible to film a better fight scene.” The Rossatron video below explains how the scene has drawn such reactions. One element has been key to Chan’s success from the beginning: his humor, visibly descended from the physical comedy of Western silent stars like Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton, which comes through even in the midst of the most intense hand-to-hand combat. In Drunken Master II, it’s “not only a pleasing addition to the film, but a necessary part of the story itself,” through the course of which Chan’s protagonist must gain control over the style of “drunken boxing” born of his own fondness for the bottle. It is controlled drunkenness, of course, that eventually brings him victory in his both cartoonish and masterful last fight, which required four months to shoot under the direction of the star himself (the film’s actual director Lau Kar-leung having ceded control of the scene due to stylistic differences). Today, there may be no action-comedy performer equal to Jackie Chan in his prime. But even if there were, would any studio allow him so much of the other secret ingredient, time? via Metafilter Related content: Kung Fu & Martial Arts Movies Online The Only Footage of Bruce Lee Fighting for Real (1967) The Graceful Movements of Kung Fu & Modern Dance Revealed in Stunning Motion Visualizations Radical French Philosophy Meets Kung-Fu Cinema in Can Dialectics Break Bricks? (1973) Why Is Jackie Chan the King of Action Comedy? A Video Essay Masterfully Makes the Case Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/07/17 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |