[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, August 6th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Emma Willard, the First Female Mapmaker in America, Creates Pioneering Maps of Time to Teach Students about Democracy (Circa 1851)

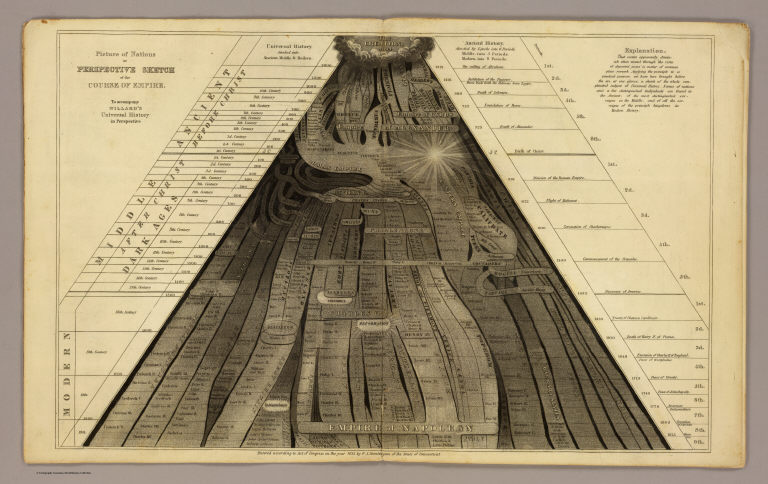

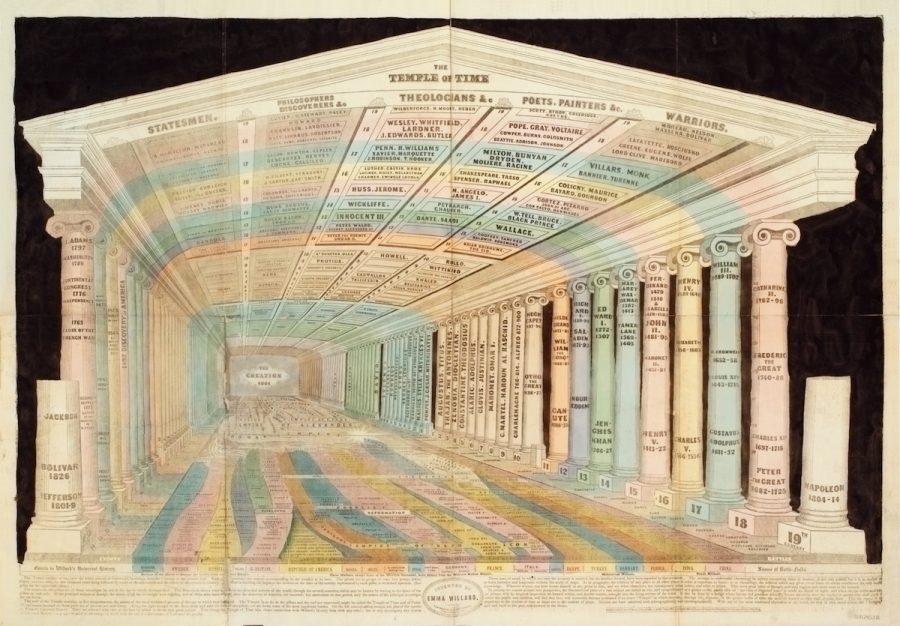

We all know Marshall McLuhan’s pithy, endlessly quotable line “the medium is the message,” but rarely do we stop to ask which one comes first. The development of communication technologies may genuinely present us with a chicken or egg scenario. After all, only a culture that already prized constant visual stimuli but grossly undervalued physical movement would have invented and adopted television. In Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord ties the tendency toward passive visual consumption to “commodity fetishism, the domination of society by ‘intangible as well as tangible things,’ which reaches its absolute fulfillment in the spectacle, where the tangible world is replaced by a selection of images which exist above it, and which simultaneously impose themselves as the tangible par excellence.” It seems an apt description of a screen-addicted culture. What can we say, then, of a culture addicted to charts and graphs? Earliest examples of the form were often more elaborate than we’re used to seeing, hand-drawn with care and attention. They were also not coy about their ambitions: to condense the vast dimensions of space and time into a two-dimensional, color-coded format. To tidily sum up all human and natural history in easy-to-read visual metaphors. This was as much a religious project as it was a philosophical, scientific, historical, political, and pedagogical one. The domains are hopelessly entwined in the 18th and 19th centuries. We should not be surprised to see them freely mingle in the earliest infographics. The creators of such images were polymaths, and deeply devout. Joseph Priestley, English chemist, philosopher, theologian, political theorist and grammarian, made several visual chronologies representing “the lives of two thousand men between 1200 BC and 1750 AD” (conveying a clear message about the sole importance of men). “After Priestley,” writes the Public Domain Review, “timelines flourished, but they generally lacked any sense of the dimensionality of time, representing the past as a uniform march from left to right.” Emma Willard, “one of the century’s most influential educators” set out to update the technology, “to invest chronology with a sense of perspective.” In her 1836 Picture of Nations; or Perspective Sketch of the Course of Empire, above (view and download high resolution images here), she presents “the biblical Creation as the apex of a triangle that then flowed forward in time and space toward the viewer.”

The perspective is also a forced point of view about origins and history. But that was exactly the point: these are didactic tools meant for textbooks and classrooms. Willard, “America’s first professional female mapmaker,” writes Maria Popova, was also a “pioneering educator,” who founded “the first women’s higher education institution in the United States when she was still in her thirties…. In her early forties, she set about composing and publishing a series of history textbooks that raised the standards and sensibilities of scholarship.” Willard recognized that linear graphs of time did not accurately do justice to a three-dimensional experience of the world. Humans are “embodied creatures who yearn to locate themselves in space and time.” The illusion of space and time on the flat page was an essential feature of Willard’s underlying purpose: “laying out the ground-plan of the intellect, so far as the whole range of history is concerned.” A proper understanding of a Great Man (and at least one Great Woman, Hypatia) version of history—easily condensed, since there were only around 6,000 years from the creation of the universe—would lead to “enlightened and judicious supporters” of democracy. History is represented literally as a sacred space in Willard’s 1846 Temple of Time, its providential beginnings formally balanced in equal proportion to its every monumental stage. Willard’s intent was expressly patriotic, her trappings self-consciously classical. Her maps of time were ways of situating the nation as a natural successor to the empires of old, which flowed from the divine act of creation. They show a progressive widening of the world. “Half a century before W.E.B. Du Bois… created his modernist data visualizations for the 1900 World’s Fair,” Popova writes, The Temple of Time “won a medal at the 1851 World’s Fair in London.” Willard accompanied the infographic with a statement of intent, articulating a media theory, over a hundred years before McLuhan, that sounds strangely anticipatory of his famous dictum.

Learn more about Emma Willard’s infographic revolution at the Public Domain Review and The Marginalian. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2020. Related Content: The History of the World in One Beautiful, 5‑Foot-Long Chart (1931) 180,000 Years of Religion Charted on a “Histomap” in 1943 Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. |

| 9:00a | Watch Meshes of the Afternoon, the Experimental Short Voted the 16th Best Film of All Time It seems not to be documented whether the Santa Ana winds were blowing when Maya Deren and Alexander Hackenschmied shot Meshes of the Afternoon. But everything about the film itself suggests that they must have been, so vivid does its atmosphere of luxuriantly arid paranoia remain these 62 years later. Despite its runtime of less than fifteen minutes and the obviously modest means of its production, it’s long been canonized as not just a standard introduction to experimentalism in film studies classes, but also a critical favorite. In fact, it placed in the last Sight and Sound critics poll of the best films of all time at a respectable #16, above Abbas Kiarostami’s Close‑Up and below John Ford’s The Searchers. Meshes of the Afternoon ranks at #62 on the directors poll, a spot that sounds low until you consider that it’s shared with the likes of Late Spring, Some Like It Hot, Sátántangó, Blade Runner, and Lawrence of Arabia. Still, it’s a bit surprising that it didn’t come in higher, given the obvious influence both direct and indirect of its early Los Angeles-noir surrealism on so many subsequent major motion pictures. “Had Californian sunlight ever looked as suggestive or sinister before the sharply etched dream world of Meshes of the Afternoon?” asks Ian Christie in his short accompanying essay at the British Film Institute’s site. “Certainly, it soon would, in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity and many later films noirs” — not to mention the “many traditions over eight decades” it has inspired since. Those include the oeuvre of the late David Lynch, which constitutes a tradition unto itself, but even the most casual filmgoer could hardly watch Meshes of the Afternoon without feeling deep resonances between it and a great many of the non-experimental movies they’ve seen since. The story, such as one can decipher it, has to do with a woman alone at home, haunted by a glimpse of a hooded figure with a mirror for a face and unable to tell whether she’s on the inside or outside of a dream. By the end, she is dead, but on which plane of reality? There are, of course, no answers, just as there is no dialogue, explanatory or otherwise. But Deren and Hackenschmied knew they didn’t need it, being fully aware that they were working in a medium where everything important can be conveyed visually — and, ideally, experienced by viewers just as if they were dreaming it themselves. The film will be added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More. Related Content: A Page of Madness: The Lost, Avant Garde Masterpiece from Early Japanese Cinema (1926) The Experimental Abstract Films of Pioneering American Animator Mary Ellen Bute (1930s-1950s) Watch Dziga Vertov’s A Man with a Movie Camera: The 8th Best Film Ever Made Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/08/06 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |