[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Wednesday, August 13th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Behold the Very First Color Photograph (1861): Taken by Scottish Physicist & Poet James Clerk Maxwell

Since its ancient origins as the camera obscura, the photographic camera has always mimicked the human eye, allowing light to enter an aperture, then projecting an image upside down. Renaissance artists relied on the camera obscura to sharpen their own visual perspectives. But it wasn’t until photography—the ability to reproduce the obscura’s images—that the rudimentary artificial eye began evolving the same complex structures we rely on for our own visual acuity: lenses for sharpness, variable apertures, shutter speeds, focus controls…. Only when it began to seem that photography might vie with the other fine arts did the development of camera technology take off. And it moved quickly. Between the time of the first photograph in 1826 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce and 1861, photography had advanced sufficiently that physicist James Clerk Maxwell—known for his “Maxwell’s Demon” thought experiment—produced the first color photograph that did not immediately fade or require hand painting (above). The Scottish scientist chose to take a picture of a tartan ribbon, “created,” writes National Geographic, “by photographing it three times through red, blue, and yellow filters, then recombining the images into one color composite.” Maxwell’s three-color method was intended to mimic the way the eye processes color, based on theories he had elaborated in an 1855 paper.

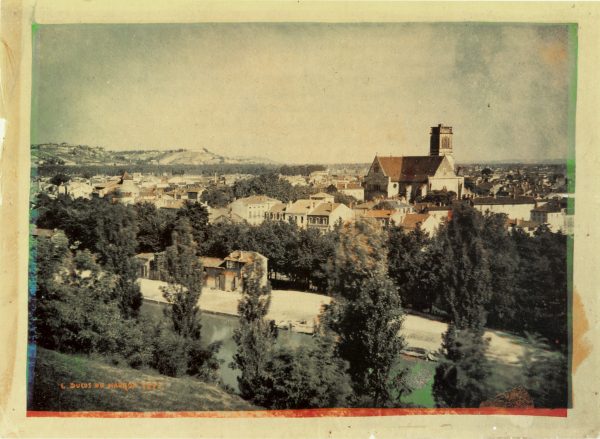

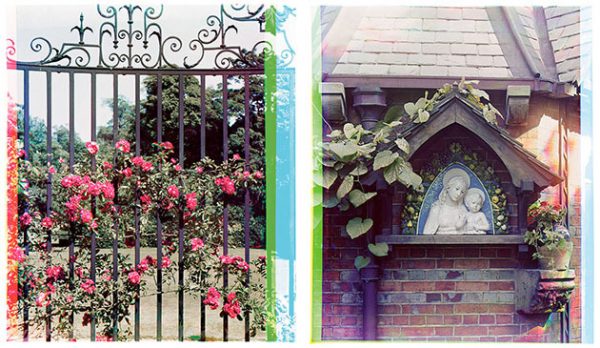

Maxwell created the image with the help of photographer Thomas Sutton, inventor of the single lens reflex camera, but his interest lay principally in its demonstration of his color theory, not its application to photography in general. Sixteen years later, the reproduction of color had not advanced significantly, though a subtractive method allowed more subtlety of light and shade, as you can see in the 1877 example above by Louis Ducos du Hauron. Even so, these nineteenth-century images still cannot compete for vibrancy and lifelikeness with hand-colored photos from the period. Despite appearing artificial, hand-tinted images like these of 1860s Samurai Japan brought a startling immediacy to their subjects in a way that early color photography did not.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2016. Related Content: The First Photograph Ever Taken (1826) Hand-Colored 1860s Photographs Reveal the Last Days of Samurai Japan The First Color Portrait of Leo Tolstoy, and Other Amazing Color Photos of Czarist Russia (1908) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| 9:00a | Tim Burton Visits a Paris Video Store & Talks About His Favorite Movies Tim Burton grew up watching Japanese monster movies in Burbank, which must explain a good deal about his artistic sensibility. It seems to be for that reason, in any case, that the new Konbini “Vidéo Club” episode above takes him first to the Asian cinema section of JM Vidéo, one of Paris’ last two DVD rental shops. Early and repeated exposure to such kaiju classics as Honda Ishirō’s Godzilla and The War of the Gargantuas may have instilled him with an affection for poor English dubbing, but it didn’t rob him of his ability to appreciate more refined (if equally visceral) examples of Japanese film like Shindō Kaneto’s Onibaba and Kuroneko. Burton describes those pictures as dreamlike, a quality he goes on to praise in other selections from a variety of different eras and cultures. Even cinephiles who don’t share his particular taste in viewing material — bound on one end, it seems, by The Passion of Joan of Arc and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, and on the other by I Was a Teenage Werewolf and The Brain That Wouldn’t Die, with the likes of Jason and the Argonauts and The Fly in between — have to admit that this indicates a deep understanding of cinema itself. It may be the art form whose experience is most similar to dreaming, but only occasionally throughout its history have particular films attained the status of the truly oneiric. One suspects that Burton knows them all. In fact, one of the twenty-first century’s most notable additions to the canon of the dreamlike won the Palme d’Or with Burton’s involvement. This video includes his brief reminiscences of being on the jury at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival, where Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives took the top prize. That same year saw the release of Burton’s own Alice in Wonderland, which he describes as “the most chaotic movie I’ve ever made.” In 2019, he directed his second live-action Disney adaptation Dumbo, which, though hardly a passion project, wasn’t without its autobiographical resonances: “At that point, I kind of felt like Dumbo,” he admits, “a weird creature trapped at Disney.” Perhaps that long on-and-off corporate association finally having come to an end, or so he suggests, means he’ll now be freer than ever to draw from the depths of his own cinematic subconsciousness. Related content: Tim Burton: A Look Inside His Visual Imagination Watch Vincent, Tim Burton’s Animated Tribute to Vincent Price & Edgar Allan Poe (1982) Tim Burton’s Hansel and Gretel Shot on 16mm Film with Amateur Japanese Actors (1983) David Cronenberg Visits a Video Store & Talks About His Favorite Movies Watch The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, the Influential German Expressionist Horror Film (1920) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/08/13 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |