[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, August 14th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | The Stunt That Ended Buster Keaton’s Brilliant Career https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yHoT_Qch Buster Keaton’s penchant and skill for comedic stunts made him one of the biggest stars of the silent-film era. Nobody at the time imagined that he would still be engaging in dangerous-looking pratfalls 40 years later in his seventies, especially since his career seemed to have come to an end in 1926. That was the year of his Civil War-set film The General, which, though now critically respected, left contemporary audiences cold. Flops are, perhaps, inevitable, but this one happened to incorporate into the picture the most expensive shot in cinema history to date. As a result, says the Ming video above, “Keaton was never given control over his films again.” Ironically, unlike the cinematic images that had made him famous, the $42,000 shot in The General did not put its director-star in apparent mortal peril, depicting only a railroad bridge collapsing while a train crosses it. Though undoubtedly impressive, it wouldn’t have been what people went to a Buster Keaton movie to see. Here was a man willing, after all, to fly from the back of a moving streetcar, dangle off the edge of a waterfall, risk being crushed by an entire wall of a house, and even break his neck — though he didn’t discover that he’d done so until eleven years later. Making these and all of Keaton’s other famous stunts involved considerable amounts of both calculated danger and movie magic. Some of that movie magic was conceived by Keaton himself, the first filmmaker, in Quentin Tarantino’s words, to “use cinema itself to be the joke.” Few performers could have adapted so well to the medium of silent film, with its realms of silent comedy just waiting to be opened. And after sound had been around for a few decades, longtime moviegoers started to feel like cinema had lost some of the visual exuberance that it once possessed. By that time, luckily, Keaton had emerged from his long post-General period of hard-drinking malaise, ready to appear not just in the movies again, but also on television, delighting the generations who remembered his earlier work and fascinating those too young to recognize him. Even today, when we find ourselves laughing at a scene of elaborately orchestrated physical danger, we are, in some sense, witnessing Keaton’s legacy. Related content: Watch the Only Time Charlie Chaplin & Buster Keaton Performed Together On-Screen (1952) A Supercut of Buster Keaton’s Most Amazing Stunts 101 Free Silent Films: The Great Classics The General, “Perhaps the Greatest Film Ever Made,” and 20 Other Buster Keaton Classics Free Online Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

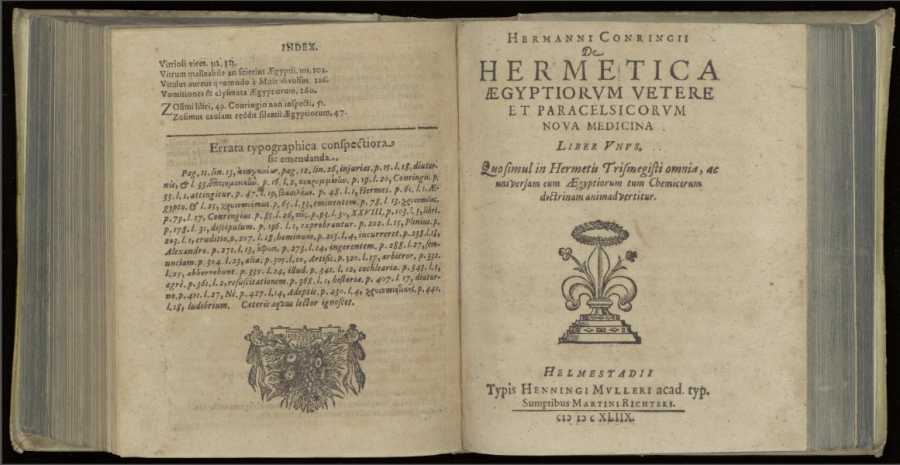

| 9:00a | 2,178 Occult Books Now Digitized & Put Online, Thanks to the Ritman Library and Da Vinci Code Author Dan Brown

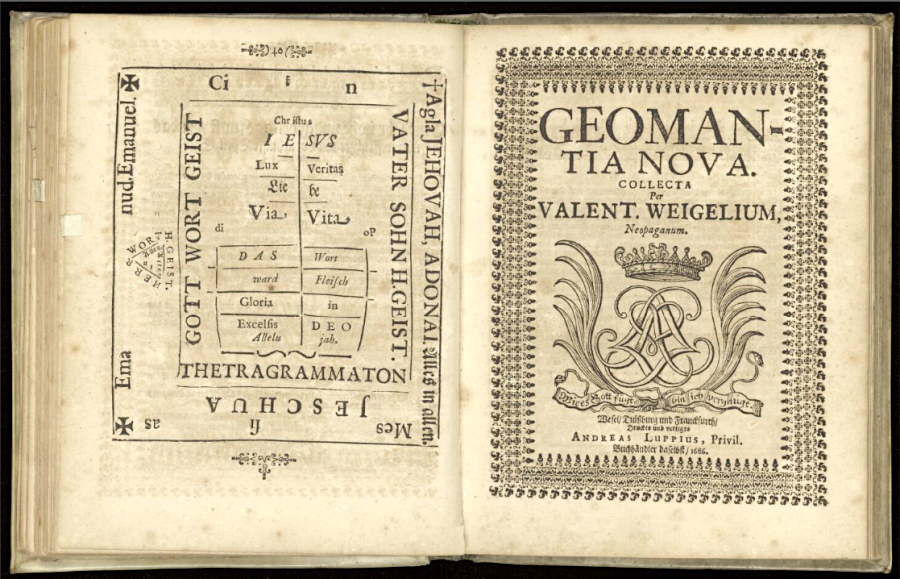

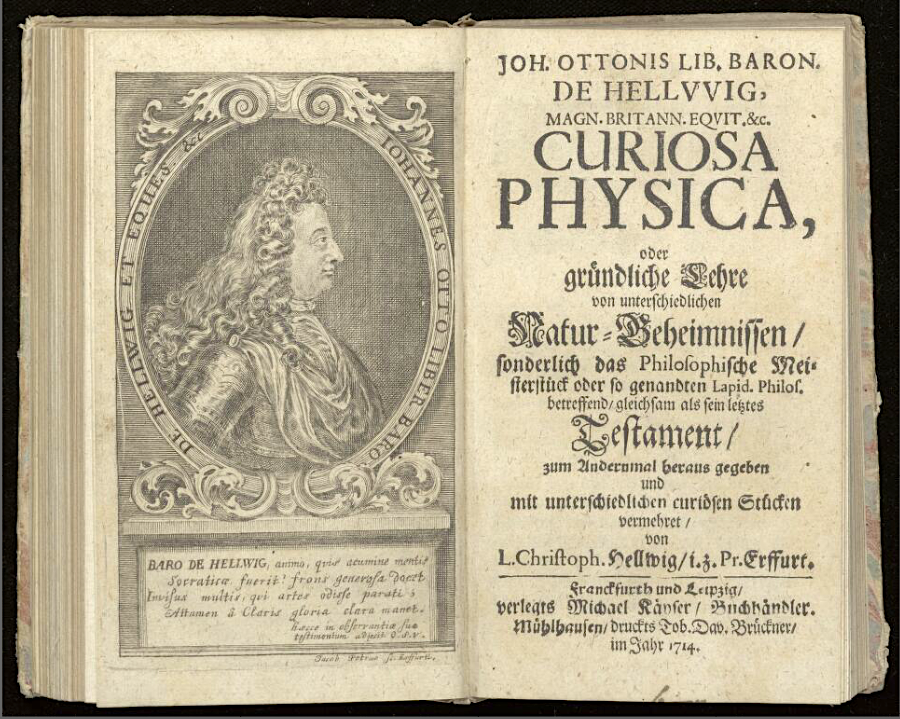

In 2018 we brought you some exciting news. Thanks to a generous donation from Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown, Amsterdam’s Ritman Library—a sizable collection of pre-1900 books on alchemy, astrology, magic, and other occult subjects—has been digitizing thousands of its rare texts under a digital education project cheekily called “Hermetically Open.” We are now pleased to report that the first 2,178 books from the Ritman project have come available in their online reading room.

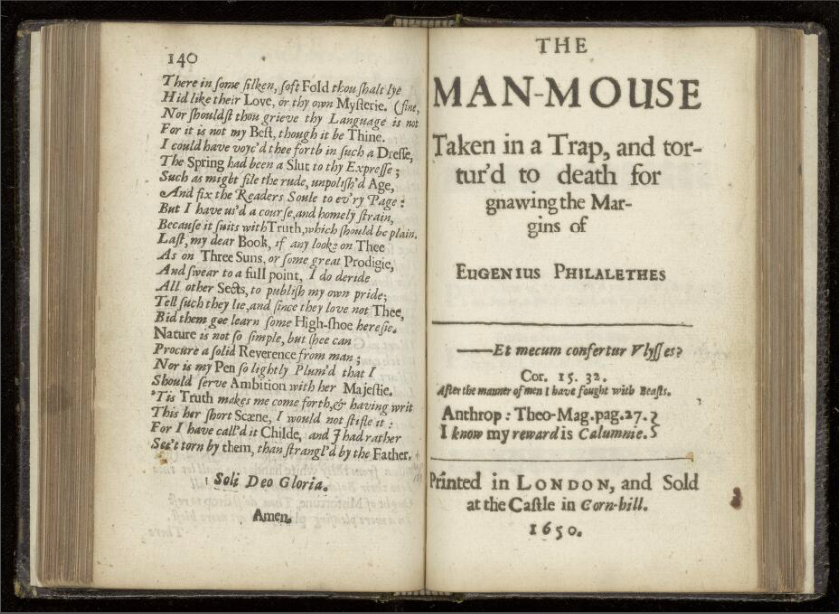

Visitors should be aware that these books are written in several different European languages. Latin, the scholarly language of Europe throughout the Medieval and Early Modern periods, predominates, and it’s a peculiar Latin at that, laden with jargon and alchemical terminology. Other books appear in German, Dutch, and French. Readers of some or all of these languages will of course have an easier time than monolingual English speakers, but there is still much to offer those visitors as well. In addition to the pleasure of paging through an old rare book, even virtually, English speakers can quickly find a collection of readable books by clicking on the “Place of Publication” search filter and selecting Cambridge or London, from which come such notable works as The Man-Mouse Takin in a Trap, and tortur’d to death for gnawing the Margins of Eugenius Philalethes, by Thomas Vaughan, published in 1650.

The language is archaic—full of quirky spellings and uses of the “long s”—and the content is bizarre. Those familiar with this type of writing, whether through historical study or the work of more recent interpreters like Aleister Crowley or Madame Blavatsky, will recognize the many formulas: The tracing of magical correspondences between flora, fauna, and astronomical phenomena; the careful parsing of names; astrology and lengthy linguistic etymologies; numerological discourses and philosophical poetry; early psychology and personality typing; cryptic, coded mythology and medical procedures. Although we’ve grown accustomed through popular media to thinking of magical books as cookbooks, full of recipes and incantations, the reality is far different.

Encountering the vast and strange treasures in the online library, one thinks of the type of the magician represented in Goethe’s Faust, holed up in his study,

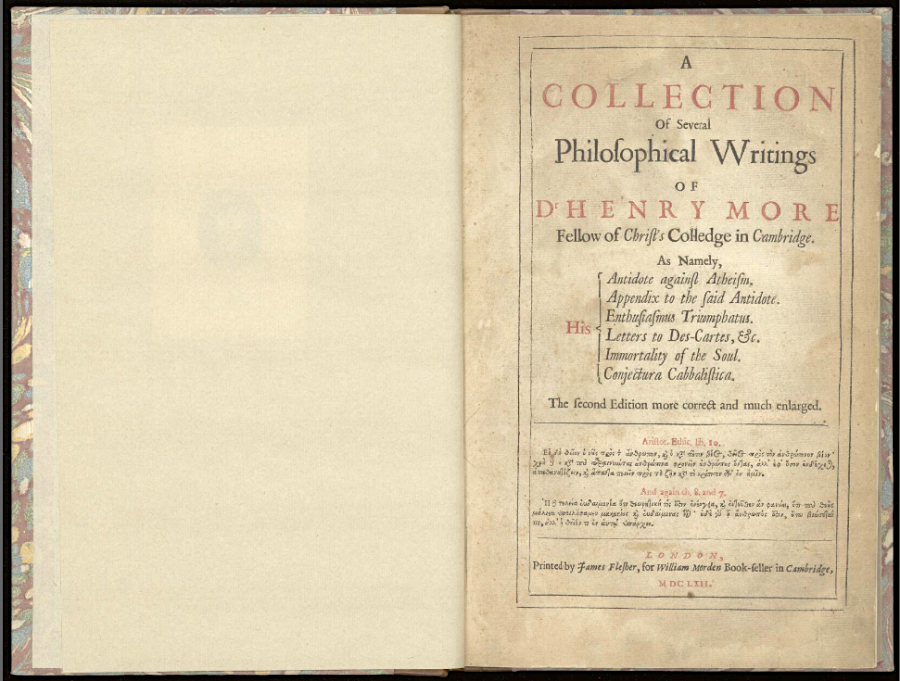

The library doesn’t only contain occult books. Like the weary scholar Faust, alchemists of old “studied now Philosophy / And Jurisprudence, Medicine,— / And even, alas! Theology.” Click on Cambridge as the place of publication and you’ll find the work above by Henry More, “one of the celebrated ‘Cambridge Platonists,’” the Linda Hall Library notes, “who flourished in mid-17th-century and did their best to reconcile Plato with Christianity and the mechanical philosophy that was beginning to make inroads into British natural philosophy.” Those who study European intellectual history know well that More’s presence in this collection is no anomaly. For a few hundred years, it was difficult, if not impossible, to separate the pursuits of theology, philosophy, medicine, and science (or “natural philosophy”) from those of alchemy and astrology. (Isaac Newton is a famous example of a mathematician/scientist/alchemist/believer in strange apocalyptic predictions.) Enter the Ritman’s new digital collection of occult texts here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2018. Related Content: Discover The Key of Hell, an Illustrated 18th-Century Guide to Black Magic (1775) Aleister Crowley Reads Occult Poetry in the Only Known Recordings of His Voice (1920) The Surreal Paintings of the Occult Magician, Writer & Mountaineer, Aleister Crowley Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/08/14 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |