[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Monday, August 18th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | Why Knights Fought Snails in Medieval Illuminated Manuscripts The snail may leave a trail of slime behind him, but a little slime will do a man no harm… whilst if you dance with dragons, you must expect to burn. - George R. R. Martin, The Mystery Knight As any Game of Thrones fan knows, being a knight has its downsides. It isn’t all power, glory, advantageous marriages and gifts ranging from castles to bags of gold. Sometimes you have to fight a truly formidable opponent. We’re not talking about bunnies here, though there’s plenty of documentation to suggest medieval rabbits were tough customers. As Vox Almanac’s Phil Edwards explains, above, the many snails littering the margins of 13th-century manuscripts were also fearsome foes. Boars, lions, and bears we can understand, but … snails? Why? Theories abound.

Detail from Brunetto Latini’s Li Livres dou Tresor Edwards favors the one in medievalist Lilian M. C. Randall’s 1962 essay “The Snail in Gothic Marginal Warfare.” Randall, who found some 70 instances of man-on-snail combat in 29 manuscripts dating from the late 1200s to early 1300s, believed that the tiny mollusks were stand ins for the Germanic Lombards who invaded Italy in the 8th century. After Charlemagne trounced the Lombards in 772, declaring himself King of Lombardy, the vanquished turned to usury and pawnbroking, earning the enmity of the rest of the populace, even those who required their services. Their profession conferred power of a sort, the kind that tends to get one labelled cowardly, greedy, malicious … and easy to put down. Which rather begs the question why the knights going toe-to- …uh, facing off against them in the margins of these illuminated manuscripts look so damn intimidated. (Conversely why was Rex Harrison’s Dr. Dolittle so unafraid of the Giant Pink Sea Snail?)

Detail from from MS. Royal 10 IV E (aka the Smithfield Decretals) Let us remember that the doodles in medieval marginalia are editorial cartoons wrapped in enigmas, much as today’s memes would seem, 800 years from now. Whatever point—or joke—the scribe was making, it’s been obscured by the mists of time. And these things have a way of evolving. The snail vs. knight motif disappeared in the 14th-century, only to resurface toward the end of the 15th, when any existing significance would very likely have been tailored to fit the times.

Detail from The Macclesfield Psalter Other theories that scholars, art historians, bloggers, and armchair medievalists have floated with regard to the symbolism of these rough and ready snails haunting the margins: The Resurrection The high clergy, shrinking from problems of the church The slowness of time The insulation of the ruling class The aristocracy’s oppression of the poor A critique of social climbers Female sexuality (isn’t everything?) Virtuous humility, as opposed to knightly pride The snail’s reign of terror in the garden (not so symbolic, perhaps…) A practical-minded Reddit commenter offers the following commentary: I like to imagine a monk drawing out his fantastical daydreams, the snail being his nemesis, leaving unsightly trails across the page and him building up in his head this great victory wherein he vanquishes them forever, never again to be plagued by the beastly buggers while creating his masterpieces. Readers, any other ideas?

Detail from The Gorleston Psalter Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019. Related Content: Killer Rabbits in Medieval Manuscripts: Why So Many Drawings in the Margins Depict Bunnies Going Bad Medieval Cats Behaving Badly: Kitties That Left Paw Prints … and Peed … on 15th Century Manuscripts A Rabbit Rides a Chariot Pulled by Geese in an Ancient Roman Mosaic (2nd century AD) Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker in New York City. |

| 9:00a | Discover the World’s Oldest Surviving Cookbook, De Re Coquinaria, from Ancient Rome

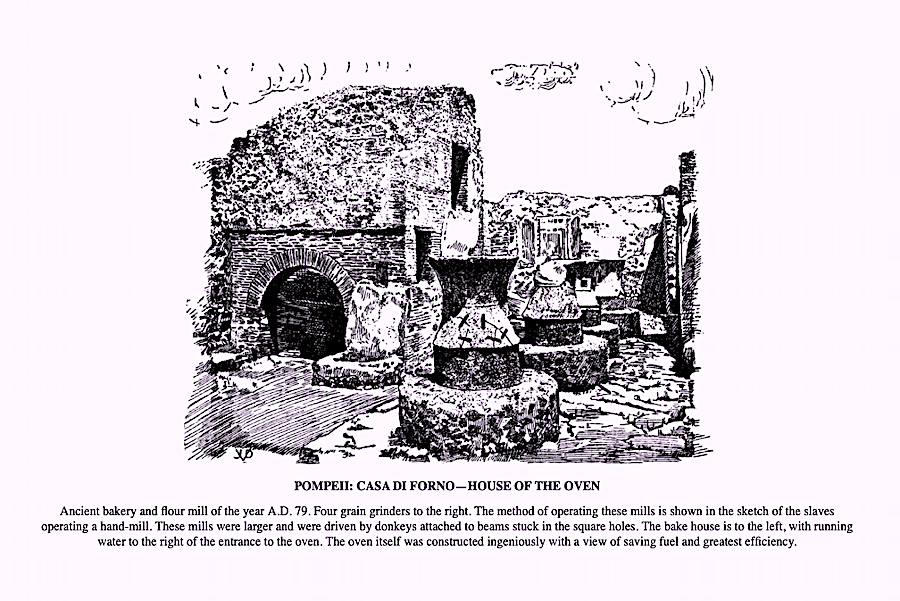

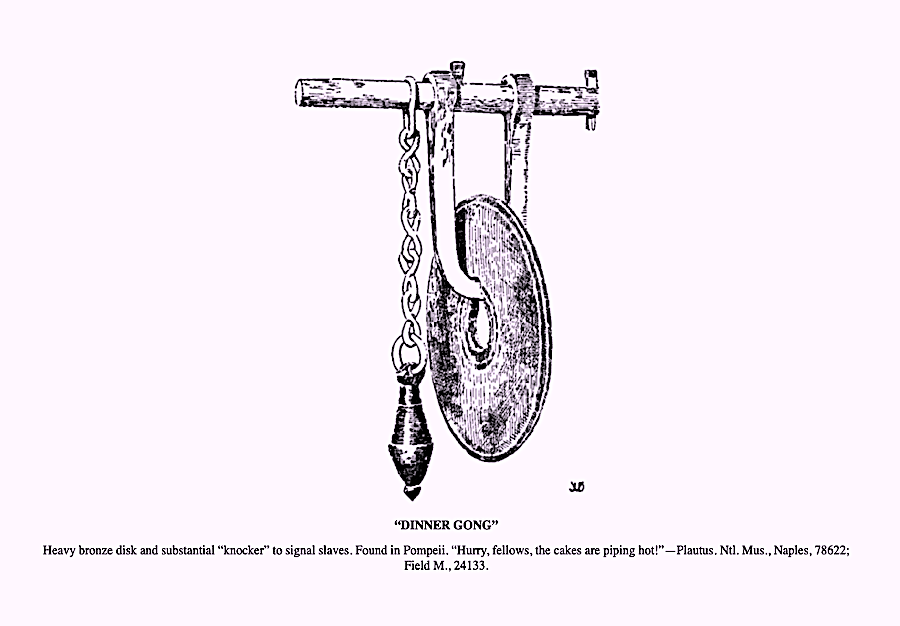

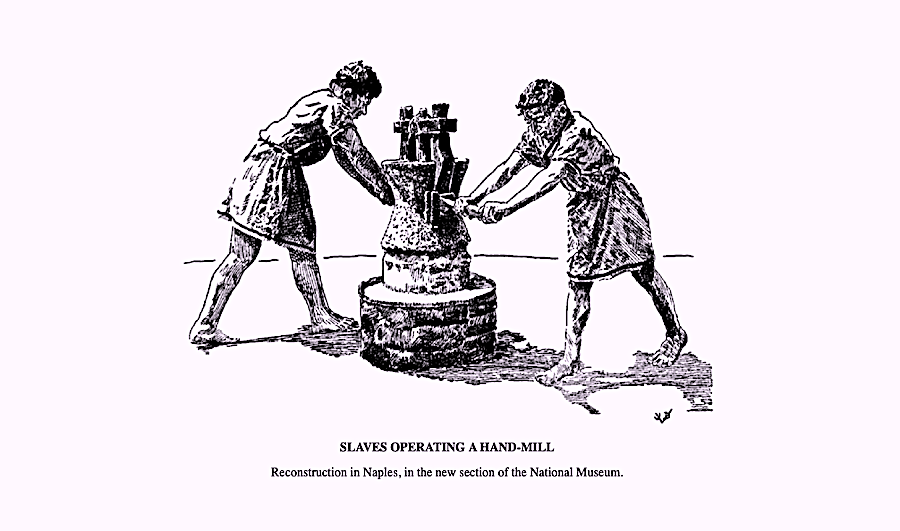

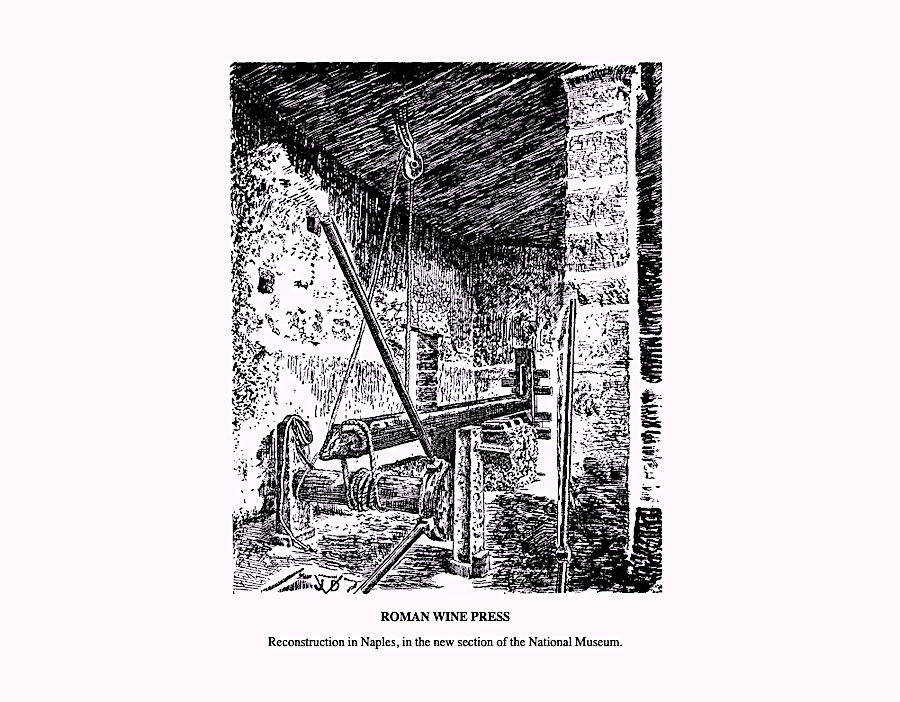

Western scholarship has had “a bias against studying sensual experience,” writes Reina Gattuso at Atlas Obscura, “the relic of an Enlightenment-era hierarchy that considered taste, touch, and flavor taboo topics for sober academic inquiry.” This does not mean, however, that cooking has been ignored by historians. Many a scholar has taken European cooking seriously, before recent food scholarship expanded the canon. For example, in a 1926 English translation of an ancient Roman cookbook, Joseph Dommers Vehling makes a strong case for the centrality of food scholarship. “Anyone who would know something worthwhile about the private and public lives of the ancients,” writes Vehling, “should be well acquainted with their table.” Published as Cookery and Dining in Imperial Rome (and available here at Project Gutenberg and at the Internet Archive), it is, he says, the oldest known cookbook in existence. The book, originally titled De Re Coquinaria, is attributed to Apicius and may date to the 1st century A.C.E., though the oldest surviving copy comes from the end of the Empire, sometime in the 5th century. As with most ancient texts, copied over centuries, redacted, amended, and edited, the original cookbook is shrouded in mystery.

The cookbook’s author, Apicius, could have been one of several “renowned gastronomers of old Rome” who bore the surname. But whichever “famous eater” was responsible, over 2000 years later the book has quite a lot to tell us about the Roman diet. (All of the illustrations here are by Vehling, who includes over two dozen examples of ancient practices and artifacts.) Meat played an important role, and “cruel methods of slaughter were common.” But the kind of meat available seems to have changed during Apicius’s time:

But vegetarians were also well-served. “Apicius certainly excels in the preparation of vegetable dishes (cf. his cabbage and asparagus) and in the utilization of parts of food materials that are today considered inferior.” This apparent need to use everything, and to sometimes heavily spice food to cover spoilage, may have led to an unusual Roman custom. As How Stuff Works puts it, “cooks then were revered if they could disguise a common food item so that diners had no idea what they were eating.”

As for the recipes themselves, well, any attempt to duplicate them will be at best a broad interpretation—a translation from ancient methods of cooking by smell, feel, and custom to the modern way of weights and measures. Consider the following recipe:

I foresee much frustrating trial and error (and many hopeful substitutions for things like lovage or rue or “satury”) for the cook who attempts this. Some foods that were plentifully available could cost hundreds now to prepare for a dinner party.

Vehling’s footnotes mostly deal with etymology and define unfamiliar terms (“laser root” is wild fennel), but they provide little practical insight for the cook. “Most of the Apician directions are vague, hastily jotted down, carelessly edited,” much of the terminology is obscure: “with the advent of the dark ages, it ceased to be a practical cookery book.” We learn, instead, about Roman ingredients and home economic practices, inseparable from Roman economics more generally, according to Vehling.

He makes a judgment of his own time even more relevant to ours: “Such atrocities as the willful destruction of huge quantities of food of every description on the one side and the starving multitudes on the other as seen today never occurred in antiquity.” Perhaps more current historians of antiquity would beg to differ, I wouldn’t know. But if you’re just looking for a Roman recipe that you can make at home, might I suggest the Rose Wine?

You could probably go with red or white, though I’d hazard Apicius went with a fine vinum rubrum. This concoction, Vehling tells us in a helpful footnote, doubles as a laxative. Clever, those Romans. Read the full English translation of the ancient Roman cookbook here. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 202o. Related Content: How to Make the Oldest Recipe in the World: A Recipe for Nettle Pudding Dating Back 6,000 BC The Oldest Unopened Bottle of Wine in the World (Circa 350 AD) Cook Real Recipes from Ancient Rome: Ostrich Ragoût, Roast Wild Boar, Nut Tarts & More How to Bake Ancient Roman Bread Dating Back to 79 AD: A Video Primer The World’s Oldest Cookbook: Discover 4,000-Year-Old Recipes from Ancient Babylon Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/08/18 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |