[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Thursday, August 28th, 2025

| Time | Event |

| 8:00a | The 1830s Device That Created the First Animations: The Phenakistiscope

The image just above is an animated GIF, a format by now older than most people on the internet. Those of us who were surfing the World Wide Web in its earliest years will remember all those little digging, jackhammering roadworkers who flanked the permanent announcements that various sites — including, quite possibly, our own — were “under construction.” Charming though they could be at the time, they now look impossibly primitive compared to what we can see on today’s internet, where high-resolution feature films stream instantaneously. But technologically speaking, we can trace it all back to what this particular animated GIF depicts: the phenakistiscope. Invented simultaneously and independently in late 1832 by Belgian physicist Joseph Plateau and Austrian geometry professor Simon Stampfer, the phenakistiscope was a simple wheel-shaped device that could, for the first time in the history of technology, create the illusion of a smoothly moving picture when spun and viewed in a mirror: hence the derivation of its name from the Greek phenakisticos, “to deceive,” and ops, “eye.” When it caught on as a commercial novelty, it was also marketed under names like Phantasmascope and Fantascope, which promised buyers a glimpse of horse-riders, twirling dancers, bowing aristocrats, hopping frogs, flying ghouls, and even proto-psychedelic abstract patterns, many of which you can see re-animated as GIFs in this Wikipedia gallery. Eventually, according to the Public Domain Review, the phenakistiscope was “supplanted in the popular imagination: firstly by the similar Zoetrope, and then — via Eadweard Muybridge’s Zoopraxiscope (which projected the animation) — by film itself.” Muybridge, previously featured here on Open Culture, did pioneering motion-photography work in the eighteen-seventies that’s now considered a precursor to cinema. Understanding what he was up to is an important part of understanding the emergence of movies as we know them. But the most instructive experience to start with is making a phenakistiscope of your own, instructions for which are available from the George Eastman Museum and artist Megan Scott on YouTube. The finished product may not hold anyone’s attention long here in the age of Netflix, but then, the age of Netflix would never have arrived had the phenakistiscope not come first. Related content: Eadweard Muybridge’s Motion Photography Experiments from the 1870s Presented in 93 Animated Gifs How Animated Cartoons Are Made: A Vintage Primer Filmed Way Back in 1919 The Trick That Made Animation Realistic: Watch a Short History of Rotoscoping Was a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema? Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

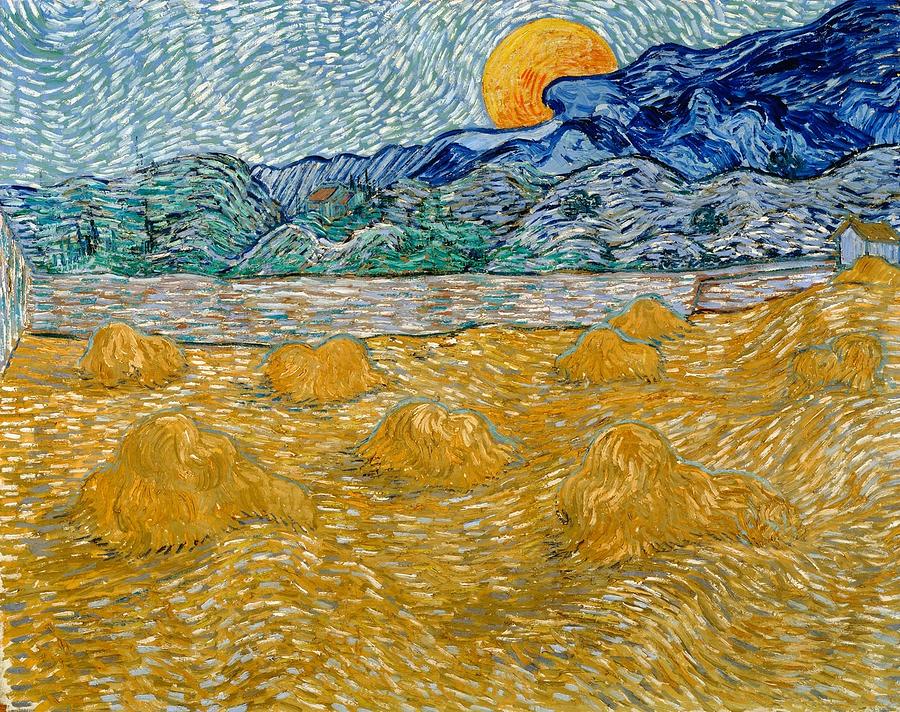

| 9:00a | 1,000+ Artworks by Vincent Van Gogh Digitized & Put Online by Dutch Museums

It gets dark before dinner now in my part of the world, a recipe for seasonal depression. Vincent van Gogh wrote about such low feelings with deep insight. “One feels as if one were lying bound hand and foot at the bottom of a deep dark well, utterly helpless.” Yet, when he looked up at the night sky he saw not darkness but blazing light: a full moon shines yellow from White House at Night like the sun, and peeks like a gold coin from behind blue mountains in Landscape with Wheat Sheaves and Rising Moon. The stars in Starry Night Over the Rhône appear like fireworks. We are all familiar with the blazing night sky of its sequel, The Starry Night.

It’s been suggested that Van Gogh saw halos of light because of lead poisoning from his paint, and that the Digitalis Dr. Gachet prescribed for his temporal lobe epilepsy caused him to “see in yellow,” the Van Gogh Gallery Blog writes, “or see yellow spots which could explain van Gogh’s consistent use of the color yellow in his later works.” His most brilliant works date from this later period, during his time at the hospital at Arles, where he painted his famous bedroom. All of these paintings, and hundreds more, can be found in high-resolution scans at the new van Gogh resource, Van Gogh Worldwide, “a consortium of museums,” notes Madeleine Muzdakis at My Modern Met, “doing their part to bring the work of one of the world’s most famous artists to the global masses.”

The museums represented here are all in the Netherlands and include the Van Gogh Museum, Kröller-Müller Museum, the Rijksmuseum, the Netherlands Institute for Art History, and the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen. Van Gogh was not only a prolific painter, of shining night scenes and otherwise, but he was “also a prolific sketch artist. His pencil and paper drawings are worth exploration; they depict landscapes as well as emotive figures from Van Gogh’s everyday life. Van Gogh Worldwide provides insight into these works of art and the artist behind them. One can also find behind-the-scenes museum information, such as details of restorations, verso (back) images, and other curatorial notes.”

Van Gogh Worldwide expands other digital collections like the Van Gogh Museum’s almost 1,000 online works. Where that resource includes short informational articles and links to literature about the artworks, Van Gogh Worldwide does not, as yet, feature such additional materials, but it does include links to Van Gogh’s letters. In one of them, he writes to his brother, Theo, about their parents: “They’ll find it difficult to understand my state of mind, and not know what drives me when they see me do things that seem strange and peculiar to them—will blame them on dissatisfaction, indifference or nonchalance, while the cause lies elsewhere, namely the desire, at all costs, to pursue what I must have for my work.” Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2020. Related Content: Vincent Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night”: Why It’s a Great Painting in 15 Minutes Download Hundreds of Van Gogh Paintings, Sketches & Letters in High Resolution Discover the Only Painting Van Gogh Ever Sold During His Lifetime Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/08/28 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |