[Most Recent Entries] [Calendar View]

Tuesday, September 23rd, 2025

| Time | Event |

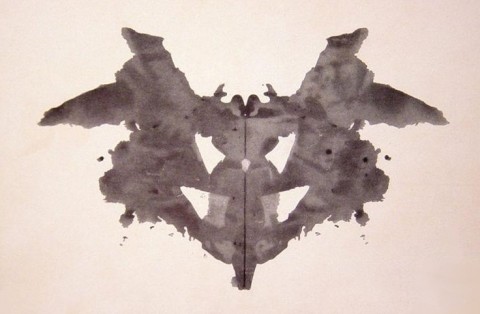

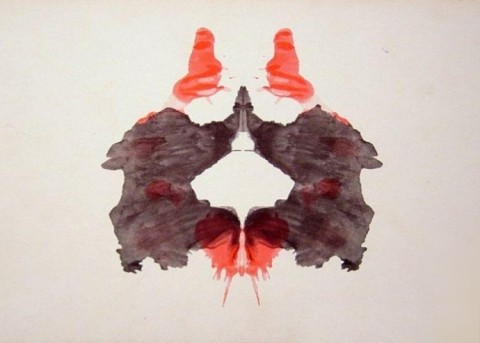

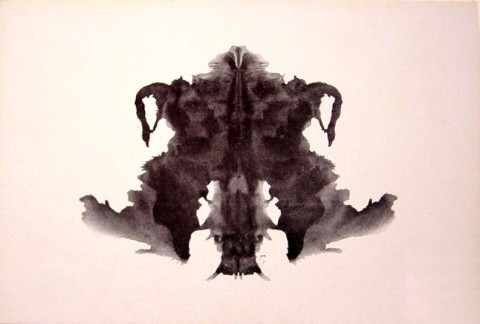

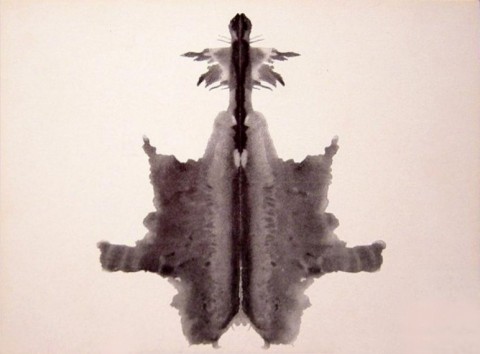

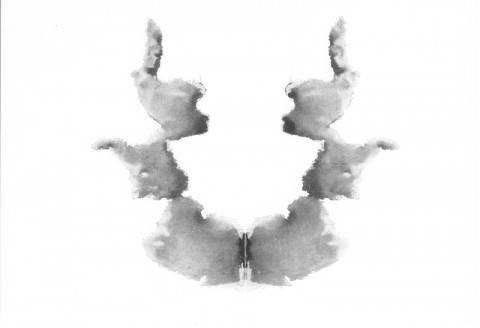

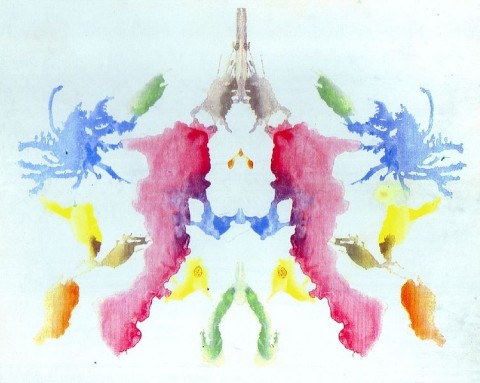

| 8:00a | Hermann Rorschach’s Original Rorschach Test: What Do You See? (1921) There is a well-known scene in Woody Allen’s Take The Money And Run (1969) when Virgil Starkwell (Allen) takes a psychological test to join the Navy, but is thwarted by his lascivious unconscious. The psychological measure that proves to be Starkwell’s undoing—rejected, he turns to a life of crime—is the Rorschach inkblot test, devised a century ago by Carl Jung’s compatriot and fellow psychologist, Hermann Rorschach. Although Rorschach would die young, at 37, his namesake remains embedded in our perception of psychology, alongside Freud’s couch and Pavlov’s dog. Hermann Rorschach’s father was an art teacher, and encouraged his son to express himself. Whether the young Rorschach had innate artistic leanings, or had begun to listen to his father more closely after the death of his mother at age 12, is uncertain. What is known, however, is that Hermann became so fascinated with making pictures out of inkblots—a Swiss game known under the delightful designation of Klecksography—that his schoolmates gave him the nickname of Klecks. Although he struggled to choose between art and science as a career, Rorschach, on the counsel of eminent German biologist and ardent Darwin supporter Ernst Haeckel, chose medicine, specializing in psychology. Still, he never abandoned art. Even before the young Rorschach began to study psychology, the medical profession had flirted with imagery association. In 1857, a German doctor named Justinus Kerner published a book of poetry, with each poem inspired by an accompanying inkblot. Alfred Binet, the father of intelligence testing, also tinkered with inkblots at the outset of the 20th century, seeing them as a potential measure of creativity. While the claim that Rorschach was familiar with these particular inkblots rests on conjecture, we know that he was familiar with the work of Szymon Hens, an early psychologist who explored his patients’ fantasies using inkblots, as well as Carl Jung’s practice of having his patients engage in word-association. After noticing that schizophrenic patients associated vastly different things with inkblots than other patients, Rorschach, following some experimentation, created the first version of the inkblot test as a measure of schizophrenia in 1921. The test, however, only came to be used as a form of personality assessment when Samuel Beck and Bruno Klopfer expanded its original scope in the late 1930s. Since then, psychologists have frequently used the various aspects of people’s responses (e.g., inkblot focus area) to make judgment calls about broad personality traits. Ironically, Rorschach himself had been skeptical about the inkblots’ value in assessing personality. In honor of Rorschach’s birthday (he was born on this day in 1884), we’ve highlighted his original images below, as well as some of the most popular responses. If you see something else in these images, feel free to let us know in the comments section below. The images, we should note, are in the public domain, and otherwise readily viewable on Wikipedia. And, according to Wikimedia Commons, the images are in the public domain. Image 1: Bat, butterfly, moth Image 2: Two humans Image 3: Two humans Image 4: Animal hide, skin, rug Image 5: Bat, butterfly, moth Image 6: Animal hide, skin, rug Image 7: Human heads or faces Image 8: Animal; not cat or dog Image 9: Human Image 10: Crab, lobster, spider, Happen to see an elephant and a men’s glee club engaged in unmentionable acts? Don’t fret—you’ve likely projected nothing intelligible. The test has long been out of date, and is deemed neither reliable nor valid in the vast majority of cases (although an updated version exists, it suffers from similar methodological flaws). Virgil Starkwell, it seems, would have made a fine Navy officer. Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture writer. Follow him at@iliablinderman |

| 9:00a | A Trip Around the World in 1900: See Restored Footage Showing Life in New York, London, India, Japan, China & Beyond From today’s vantage, the first decade of the twentieth century can look like an even more distant period of history than it is. In many corners of urban civilization, the cabarets, tearooms, and other near-paralytically mannered institutions of the Belle Époque were very much going concerns. To those who lived in that era, it must have been easy enough to believe that the ways of nineteenth-century-style aristocracy and empire could perpetuate themselves forever. Yet those were also the years of Georges Méliès Le Voyage dans la Lune, the Wright brothers’ first flight; the proliferation of automobiles and subway trains; Russia’s loss in war to Japan and first revolution; Einstein’s discovery of relativity, the photoelectric effect, and Brownian motion; and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. The world as it was, in other words, was giving way to the world as it would be. Such is the context of the documentary footage collected — and colorized, and upscaled — in the video at the top of the post. Beginning in a bustling working-class street in Hollinwood, England, this tour of the nineteen-hundreds continues on to places like Spain, India, China, New York, Japan, Brazil, Denmark, Austria, and Germany. One aspect of all this footage liable to catch the twenty-first-century eye is all the myriad forms of transportation on display, some running on solely animal or even human muscle, and others propelled by the kind of engines then at the heart of industrial revolutions the world over. (You can even catch a glimpse of Wuppertal’s suspended Schwebebahn, previously featured here on Open Culture.) All this gives us a clearer sense of why so many contemporary observers expressed feelings of civilizational whiplash, especially if, as was becoming more and more common, they’d emigrated from a less technologically advanced society to a more technologically advanced one. For those living at the edge of progress, the shape of things to come (a phrase later used as a book title by one such observer, the prolific H. G. Wells) was anyone’s guess, and it’s hardly surprising that so many forward-looking philosophies, ideologies, and art movements would arise from such a ferment. Still, it would have taken a prescient mind indeed to foresee the ascendance of communism, Nazism, the American empire, and mass broadcast media just ahead, to say nothing of two world wars. William Gibson had yet to be born, let alone to utter his now-famous quote, but as we can see, the future was already here in the nineteen-tens — and unevenly distributed. Related content: Footage of Cities Around the World in the 1890s: London, Tokyo, New York, Venice, Moscow & More Paris Had a Moving Sidewalk in 1900, and a Thomas Edison Film Captured It in Action Immaculately Restored Film Lets You Revisit Life in New York City in 1911 Berlin Street Scenes Beautifully Caught on Film (1900–1914) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| << Previous Day |

2025/09/23 [Calendar] |

Next Day >> |