Add this feed to your friends list for news aggregation, or view this feed's syndication information.

LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose.

| Wednesday, September 17th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | How a 19th Century Scientist Created Incredibly Realistic 3D Models of the Moon (1874)

At the moment, there’s no better way to see anything in space than through the lens of the James Webb Space Telescope. Previously featured here on Open Culture, that ten-billion-dollar successor to the Hubble Space Telescope can see unprecedentedly far out into space, which, in effect, means it can see unprecedentedly far back in time: some 13.5 billion years, in fact, to the state of the early universe. We posted the first photos taken by the James Webb Space Telescope in 2022, which showed us distant galaxies and nebulae at a level of detail in which they’d never been seen before.

Such images would scarcely have been imaginable to James Nasmyth, though he might have foreseen that they would one day be a reality. A man of many interests, he seems to have pursued them all during the nineteenth century through which he lived in its near-entirety. His invention of the steam hammer, which turned out to be a great boon to the shipbuilding industry, did its part to make possible his early retirement. At that point, he was freed to pursue such passions as astronomy and photography, and in 1874, he published with co-author James Carpenter a book that occupied the intersection of those fields.

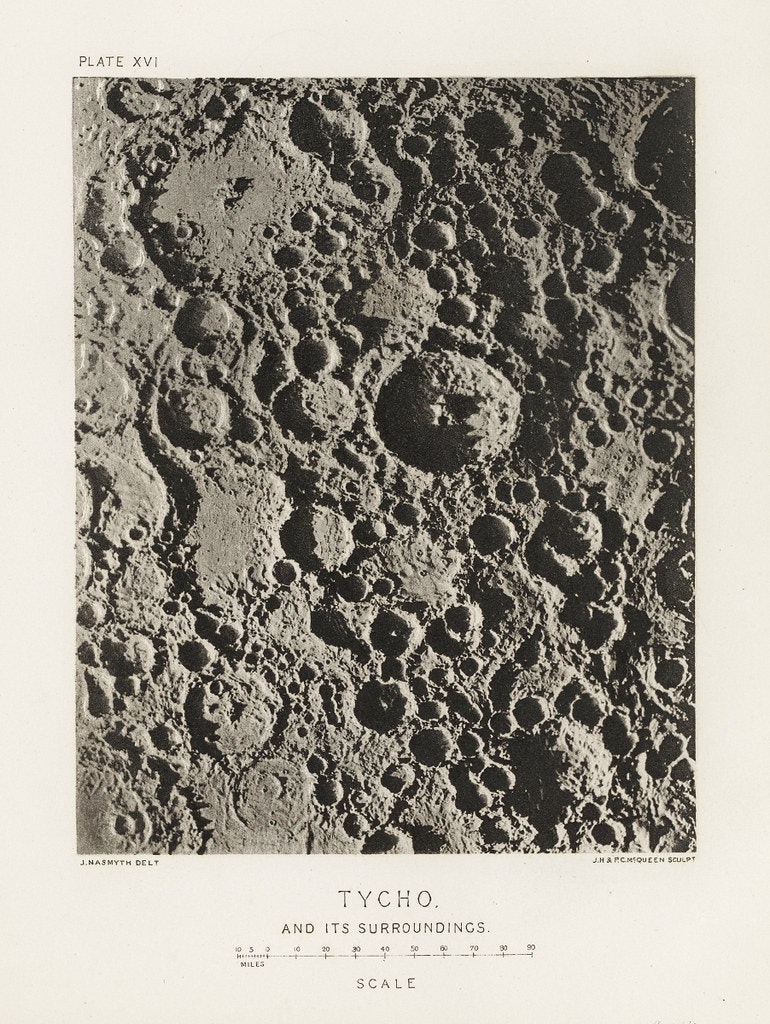

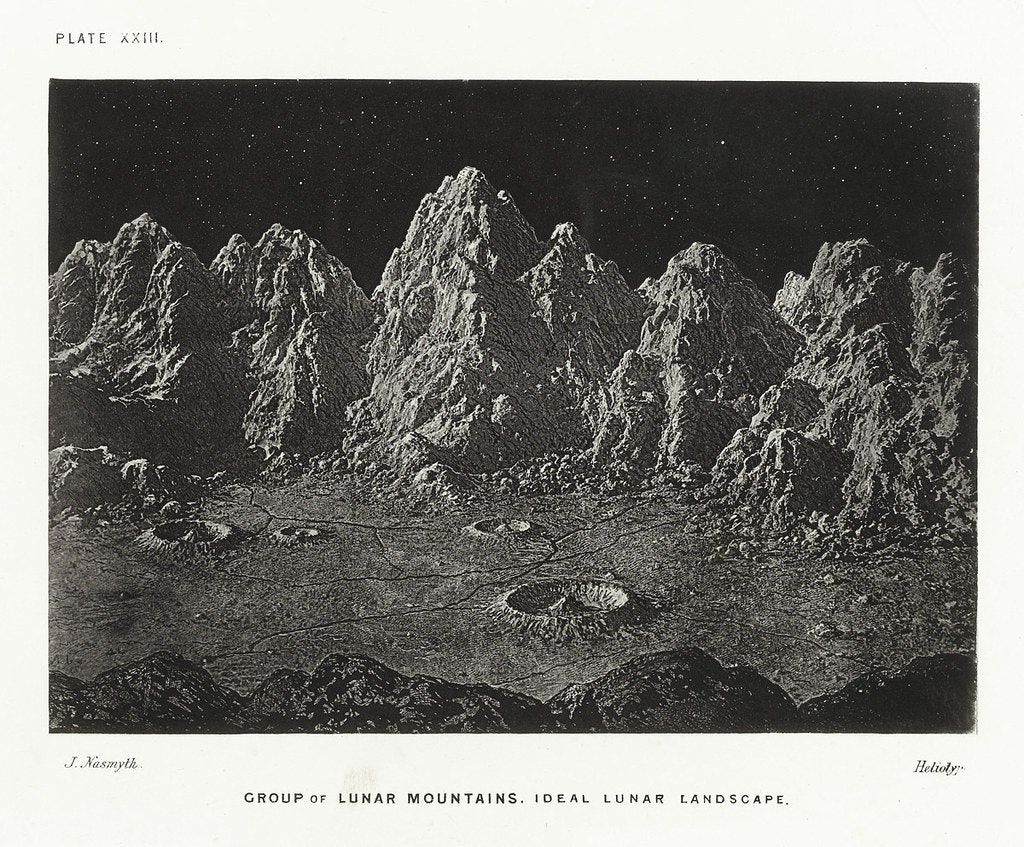

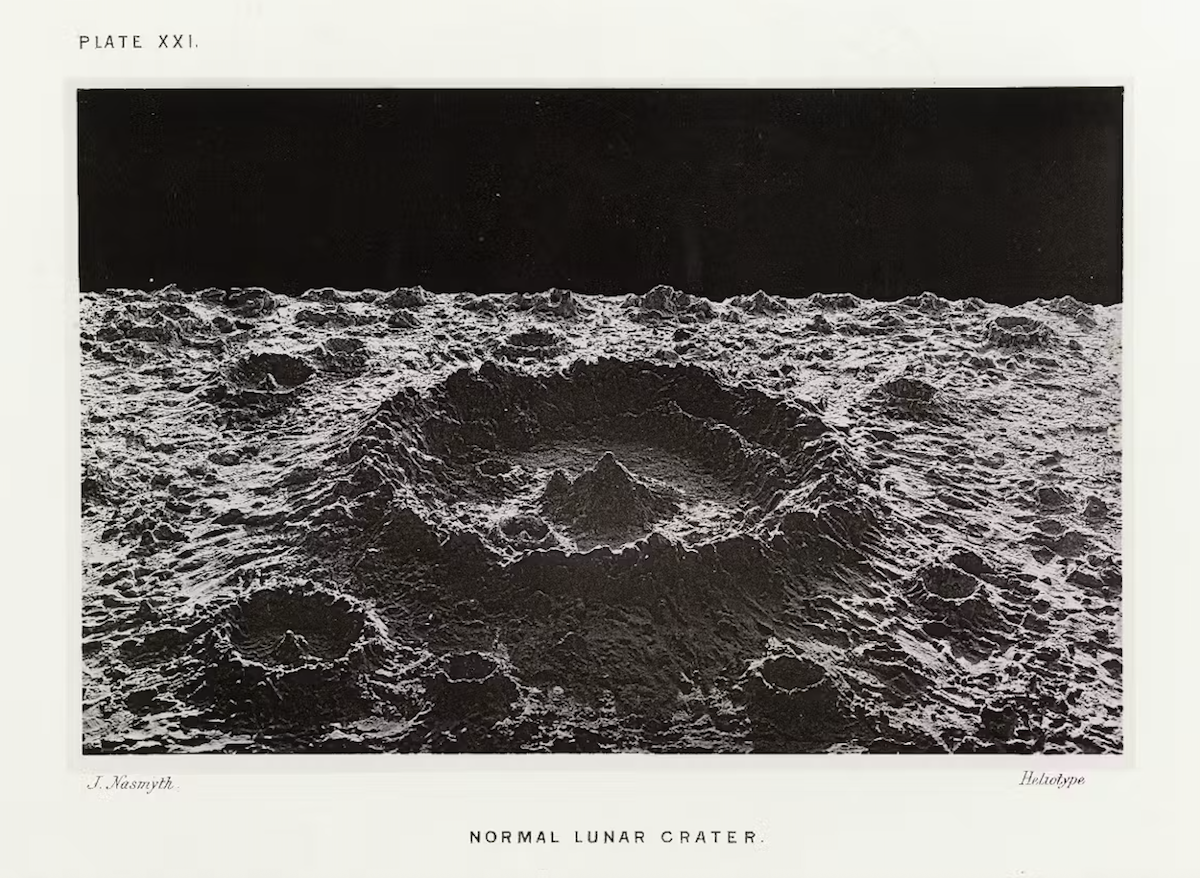

The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite contains what still look like strikingly detailed photos of the surface of that familiar but then-still-mysterious heavenly body: quite a coup at the time, considering that the technology for taking pictures through a telescope had yet to be invented. Nasmyth did use a telescope — one he made himself — but only as a reference in order to sketch “the moon’s scarred, cratered and mountainous surface,” writes Ned Pennant-Rea at the Public Domain Review. “He then built plaster models based on the drawings, and photographed these against black backgrounds in the full glare of the sun.”

In the book’s text, Nasmyth and Carpenter showed a certain scientific prescience with their observations on such phenomena as the “stupendous reservoir of power that the tidal waters constitute.” You can read the first edition at the Internet Archive, and you can see more of its photographs at the Public Domain Review. Compare them to pictures of the actual moon, and you’ll notice that he got a good deal right about the look of its surface, especially given the tools he had to work with at the time. There’s even a sense in which Nasmyth’s photos look more real than the 100 percent faithful images we have now, that they vividly represent something of the moon’s essence. As millions of disappointed viewers of CGI-saturated modern sci-fi movies understand, sometimes only models feel right. Related content: The First Surviving Photograph of the Moon (1840) The Very First Picture of the Far Side of the Moon, Taken 60 Years Ago The Full Rotation of the Moon: A Beautiful, High Resolution Time Lapse Film The Evolution of the Moon: 4.5 Billions Years in 2.6 Minutes A Trip to the Moon (1902): The First Great Sci-Fi Film Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Tuesday, September 16th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | When Michelangelo Created Artistic Designs for Military Fortifications to Protect Florence (1529–1530)

Michelangelo was born in the Republic of Florence, with the talent of… well, Michelangelo. Given those beginnings, it would have been practically impossible for him to avoid entanglement with the House of Medici, the banking family and political dynasty that ruled over Florence for the better part of three centuries. By the time of Michelangelo’s birth, in 1475, the Medici had been in power for four decades. At the age of fourteen, he was taken in by Lorenzo de’ Medici, known as “il Magnifico,” in whose household he received artistic training as well as philosophical knowledge and political connections.

It was with Lorenzo’s death in 1492 that this first streak of Medici dominance ran into choppy waters. When the family was expelled from Florence two years later, Michelangelo took his leave as well, beginning the period of his career in which he would sculpt both the Pietà and the David. Only in 1512 (after various troubles in Florence that included the four-year theocracy of Savonarola) were the Medici restored to power, but they also had the papacy: the Medici popes Leo X and Clement VII commissioned a great deal of work from Michelangelo, though he seldom saw eye-to-eye with those particular patrons.

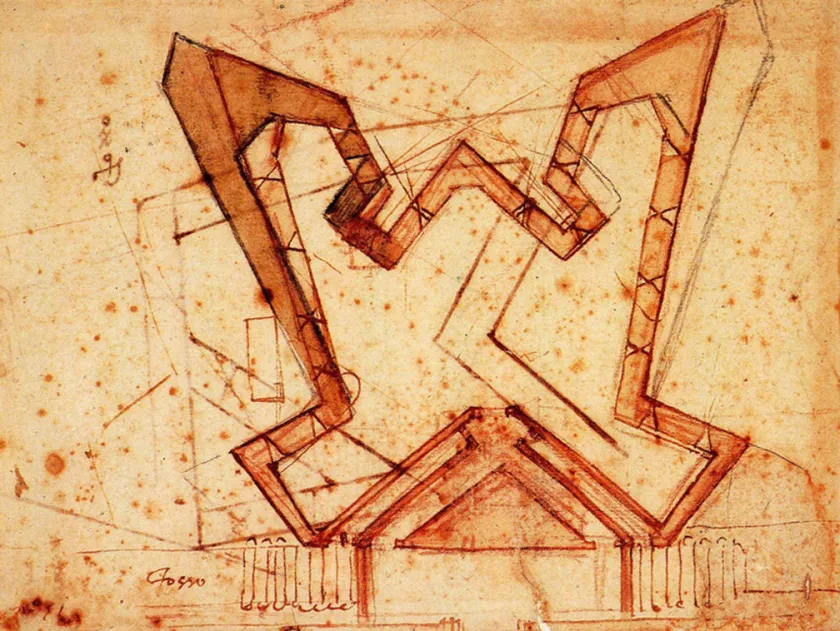

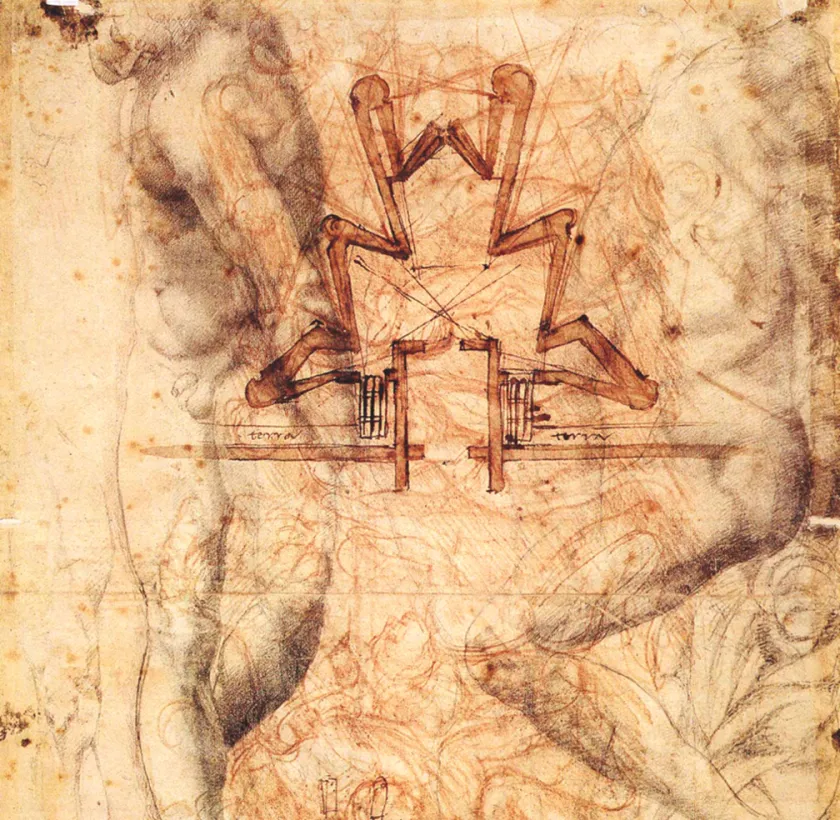

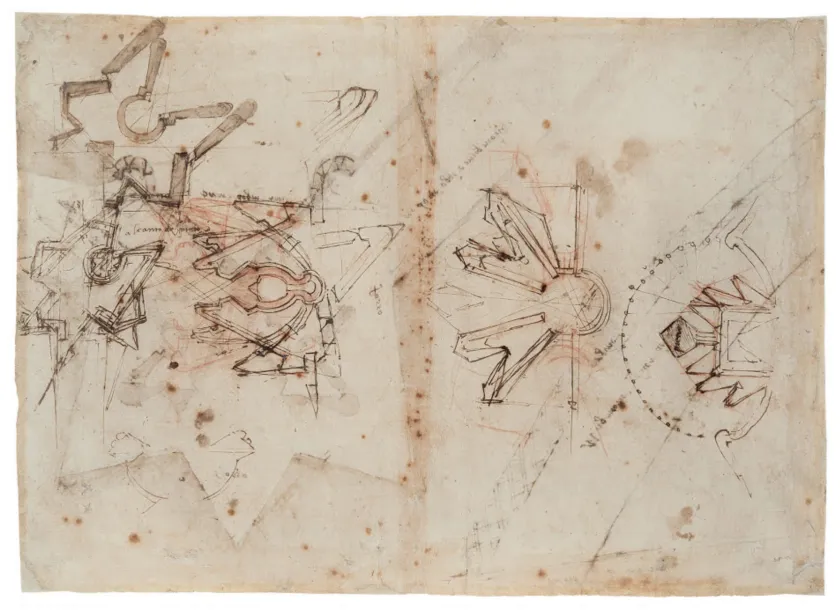

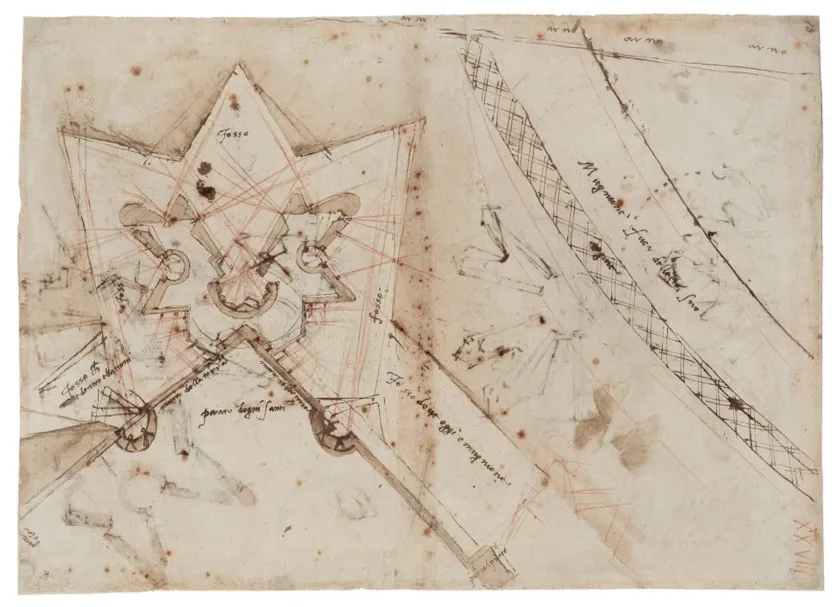

When Florence rebelled against the Medici in the late fifteen-twenties, Michelangelo took the side of the republicans. Their government selected him as one of the “Nine of the Militias” meant to design fortifications for the threatened city (a resumption of earlier, abandoned Medici plans) in 1526, and before long appointed him governatore generale. It was in that capacity that he drew the sketches seen here, which constitute his plans for a set of fortifications against the Medici-backed siege that spanned 1529 and 1530. However artistically striking, their designs were never actually built, at least not in anything like their entirety.

As it happened, Michelangelo had backed the wrong horse: the siege was ultimately successful, and the Medici retook power under the aegis of Holy Roman emperor Charles V. This put the artist in a difficult position, and for a period of months he was forced to go into hiding. With his death sentence in effect, he lay low in a small chamber beneath the Basilica of San Lorenzo, now part of the Medici Chapels Museum, whose walls are covered in drawings, previously featured here on Open Culture, in his unmistakable hand. The artistic skills he’d kept sharp during that period of internal exile would probably have kept serving him well enough in Florence after Clement VII guaranteed his safety there. But it seems he’d had enough Florentine intrigue for one lifetime, the rest of which he wisely opted to spend in Rome. Related content: A Secret Room with Drawings Attributed to Michelangelo Opens to Visitors in Florence How Michelangelo’s David Still Draws Admiration and Controversy Today New Video Shows What May Be Michelangelo’s Lost & Now Found Bronze Sculptures Watch the Painstaking and Nerve-Racking Process of Restoring a Drawing by Michelangelo Michelangelo’s Illustrated Grocery List Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Monday, September 15th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | Everything That Went Wrong During The Wizard of Oz’s Seriously Troubled Production The Wizard of Oz is now showing at Las Vegas’ Sphere. Or a version of it is, at any rate, and not one that meets with the approval of all the picture’s countless fans. “The beloved 1939 film starring Judy Garland, widely considered one of the greatest Hollywood classics, has been stretched and morphed and adapted to fit the enormous dome-shaped venue,” writes the New York Times’ Alissa Wilkinson. This entailed an extension “upward and outward with the help of A.I. as well as visual effects artists. The cool tornado created by Arnold Gillespie for the original has been traded for something digital, and eventually you can’t see it at all, because you’re inside the funnel. New performances and vistas have also been generated,” which is “at best questionable” ethically, to say nothing of the aesthetics. Yet even given the considerable modifications to — and excisions from — the original film, “most audiences will gladly overlook all of this, wowed by the sheer scale of the spectacle.” The Wizard of Oz has, as has often been said, the kind of “magic” that endures through even great deficiencies in presentation. That quality first became apparent in 1956, seventeen years after the movie’s release in cinemas, when it first aired on television. Though the dramatic transition from black-and-white to color would have been lost on most home viewers at the time, “45 million people tuned in, far more than those who had seen it in theaters,” says the narrator of the It Was A Sh*t Show video above. Another broadcast, in 1959, did even better, and thereafter The Wizard of Oz became an “annual must-see event” on TV, which eventually made it “the most-watched film in history.” That status justifies the movie’s infamously troubled production, which is the video’s central subject. From its numerous rewrites all the way through to its feeble box office performance, The Wizard of Oz encountered severe difficulties every step of the way, which gave rise to rumors that continue to haunt it: that an actor died from poison makeup, for example, or that one of the munchkins committed suicide in view of the camera. While the production caused no fatalities — at least not directly — it did come close more than once, to say nothing of the psychological toll the combination of high ambition and persistent dysfunction must have taken on many, if not most, of its participants. Even hearing enumerated only its clearly documented problems is enough to make one wonder how the picture was ever completed in the first place. Yet now, 86 years later, its Sphere reinterpretation is raking in $2 million in ticket sales per day: an act of wizardry if ever there was one. Related content: Watch the Earliest Surviving Filmed Version of The Wizard of Oz (1910) The Wizard of Oz Broken Apart and Put Back Together in Alphabetical Order The Complete Wizard of Oz Series, Available as Free eBooks and Free Audio Books Hear Waiting for Godot, the Acclaimed 1956 Production Starring The Wizard of Oz’s Bert Lahr Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Tuesday, September 16th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

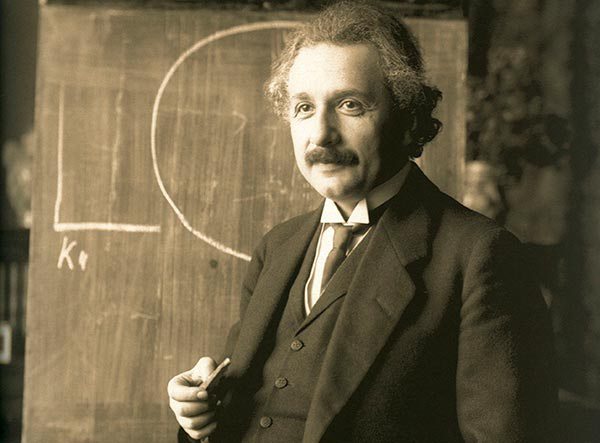

| 8:00 am | Albert Einstein Gives a Speech Praising Immigrants’ Contributions to America (1939)

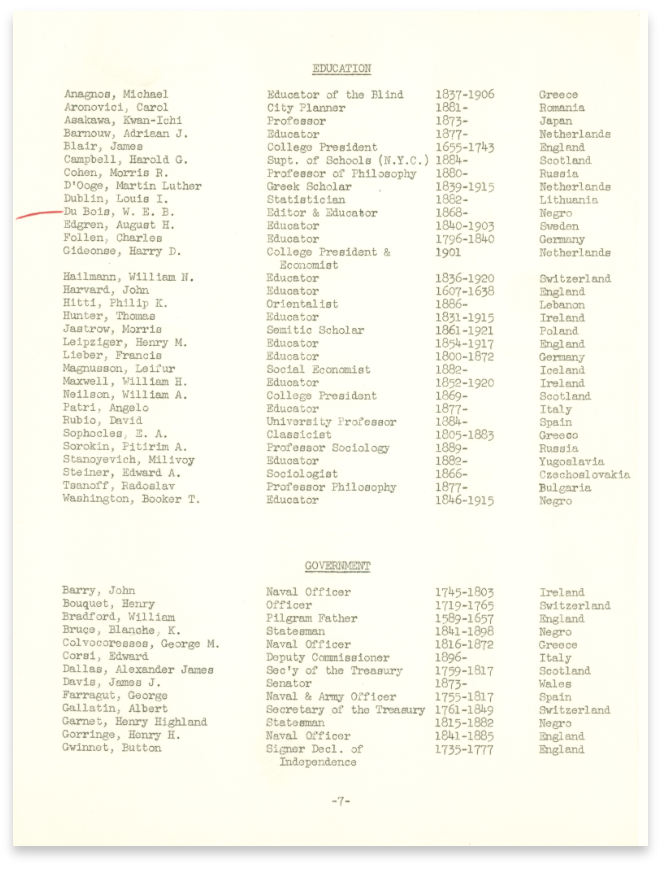

There have been many times in American history when celebrations of the country’s multi-ethnic, ever-changing demography served as powerful counterweights to narrow, exclusionary, nationalisms. In 1855, for example, the publication of Brooklyn native Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself offered a “passionate embrace of equality,” writes Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, “the soul of democracy.” We can contrast the vibrancy and dynamism of Whitman’s vision with the violent nativism of the anti-immigrant Know-Nothings, who reached their peak in the 1850s. The movement was founded by two other New Yorkers, gang leader William “Bill the Butcher” Poole and writer Thomas R. Whitney, who asked in one of his political tracts, “What is equality but stagnation?” Almost 100 years later, we see another nationalist movement taking hold, not only in Europe, but in the States. Before the U.S. entered World War II, its views on National Socialist Germany were decidedly ambivalent, with glowing portraits of its leader published throughout the 30s, and a sizable Nazi presence in the U.S. From 1934 to 1939, for example, German groups in the U.S. organized massive rallies in Madison Square Garden. Additionally, the German-American Bund promoted the Nazi Party throughout the U.S. with 70 different local chapters. These organizations held Nazi family and summer camps in New Jersey, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania…. “There were forced marches in the middle of the night to bonfires,” says historian Arnie Bernstein, “where the kids would sing the Nazi national anthem and shout ‘Sieg Heil.’”  Needless to say, these scenes made a number of minority groups and immigrants particularly nervous, especially Jews who had just escaped from Europe. One such immigrant, physicist Albert Einstein, had made the U.S. his permanent home in 1933 when he accepted a position at Princeton after living as a refugee in England. He would go on to become a forceful advocate for equality in the U.S., speaking out against the racial caste system of segregation. In 1940, Einstein gave a little-known speech at the New York World’s Fair to inaugurate an exhibit that paid “homage to the diversity of the U.S. population.” On the display, called the “Wall of Fame,” were inscribed “the names and professions of hundreds of the nation’s most notable ‘immigrants, Negroes and American Indians.’” (See the first page of the typed list above, and the full list here.) Einstein’s speech comes to us via Speeches of Note, a sibling of two favorite sites of ours, Letters of Note and Lists of Note. Below, you can read the full transcript of the speech, in which Einstein—having adopted the country as it had adopted him—-declaims, “these, too, belong to us, and we are glad and grateful to acknowledge the debt that the community owes them.”

The speech is remarkable for its egalitarianism. The exhibit works more or less as a “who’s who” of notable personalities—all of them men. Of course, Einstein himself was one of the most notable immigrants of the age. And yet, his ethos is Whitmanian, celebrating the multitudes of laborers and artists “blossoming namelessly” and those who have “remained unknown.” The country, Einstein suggests, could not possibly be itself without its diversity of people and cultures. That same year, Einstein would pass his citizenship test, and explain in a radio broadcast, “Why I am an American.” Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017. Related Content: Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio Rare Audio: Albert Einstein Explains “Why I Am an American” on Day He Passes Citizenship Test (1940) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. |

| Monday, September 15th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

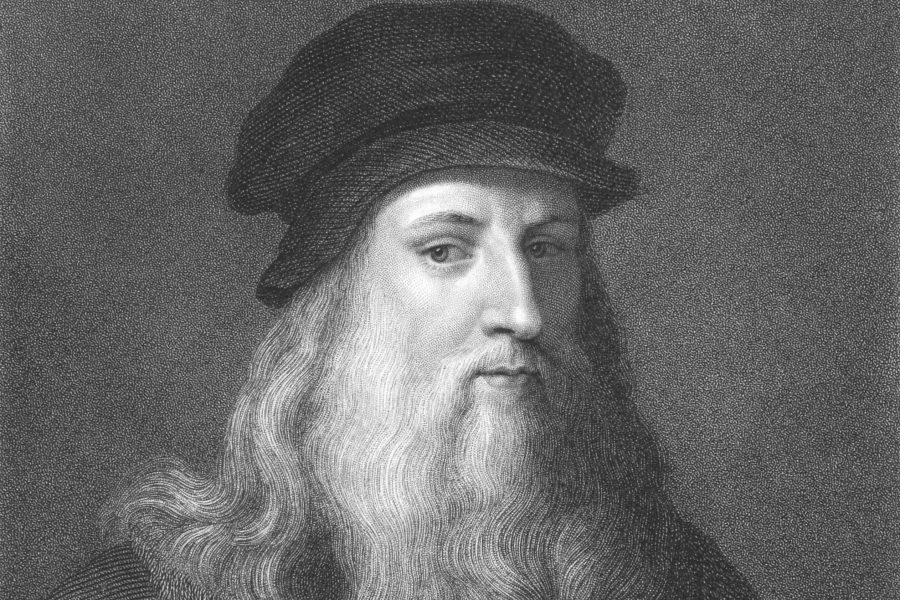

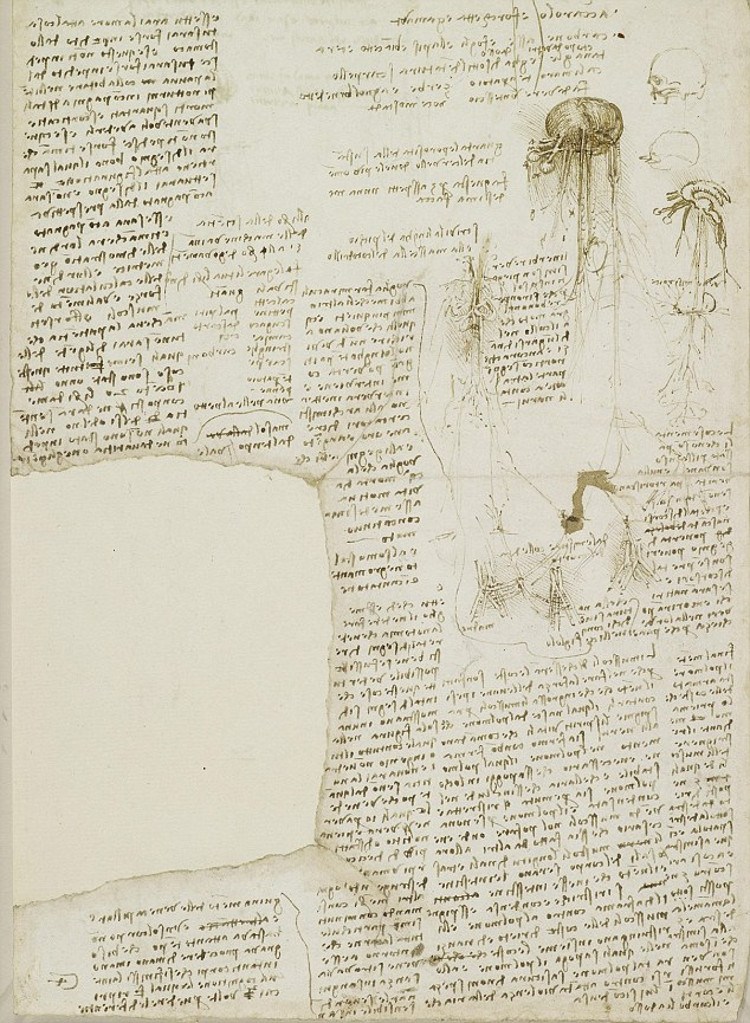

| 8:00 am | Leonardo Da Vinci’s To-Do List from 1490: The Plan of a Renaissance Man

Most people’s to-do lists are, almost by definition, pretty dull, filled with those quotidian little tasks that tend to slip out of our minds. Pick up the laundry. Get that thing for the kid. Buy milk, canned yams and kumquats at the local market. Leonardo Da Vinci was, however, no ordinary person. And his to-do lists were anything but dull. Da Vinci would carry around a notebook, where he would write and draw anything that moved him. “It is useful,” Leonardo once wrote, to “constantly observe, note, and consider.” Buried in one of these books, dating back to around the 1490s, is a to-do list. And what a to-do list. NPR’s Robert Krulwich had it directly translated. And while all of the list might not be immediately clear, remember that Da Vinci never intended for it to be read by web surfers 500 years in the future.

You can just feel Da Vinci’s voracious curiosity and intellectual restlessness. Note how many of the entries are about getting an expert to teach him something, be it mathematics, physics or astronomy. Also who casually lists “draw Milan” as an ambition?

Later to-do lists, dating around 1510, seemed to focus on Da Vinci’s growing fascination with anatomy. In a notebook filled with beautifully rendered drawings of bones and viscera, he rattles off more tasks that need to get done. Things like get a skull, describe the jaw of a crocodile and tongue of a woodpecker, assess a corpse using his finger as a unit of measurement. On that same page, he lists what he considers to be important qualities of an anatomical draughtsman. A firm command of perspective and a knowledge of the inner workings of the body are key. So is having a strong stomach. You can see a page of Da Vinci’s notebook above but be warned. Even if you are conversant in 16th century Italian, Da Vinci wrote everything in mirror script. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in December, 2014. If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day. If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks! Related Content: Leonardo da Vinci’s Handwritten Resume (Circa 1482) Thomas Edison’s Hugely Ambitious “To-Do” List from 1888 Umberto Eco Explains Why We Make Lists Johnny Cash’s Short and Personal To-Do List Jonathan Crow is a writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. |

| Friday, September 12th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | The Horrifying Paintings of Francis Bacon Mention Francis Bacon, and you sometimes have to clarify which one you mean: the twentieth-century painter, or the seventeenth-century philosopher? Despite how much time separated their lives, the two men aren’t without their connections. One may actually have been a descendant of the other, if you credit the artist’s father’s claim of relation to the Elizabethan intellectual’s half-brother. Better documented is how the more recent Francis Bacon made a connection to the time of the more distant one, by painting his own versions of Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X. We refer, of course, to his “screaming popes,” the subject of the new Hochelaga video above. As Hochelaga creator Tommie Trelawny puts it, “no image captured his imagination more” than Velázquez’s depiction of Pope Innocent X, which is “considered to be one of the finest works in Western art.” Bacon’s version from 1953, after he’d more than established himself in the English art scene, is “a terrible and frightening inversion of the original. The Pope screams as if electrocuted in his golden throne. Violent brushstrokes sweep across the canvas like bars of a cage, stripping away all sense of grandeur and leaving only brutality and pain.” In many ways, this harrowing image came as the natural meeting of existing currents in Bacon’s work, which had already drawn from the history of Christian art and employed a variety of anguished, isolated figures. Unsurprisingly, Bacon’s Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X inspired all manner of controversy. The artist himself denied all interpretations of its supposed implications, insisting that “recreating this papal portrait was simply an aesthetic choice: art for the sake of art.” In any case, he followed it up with about 50 more screaming popes, each of which “embodies a different facet of human darkness.” These and the many other works of art Bacon created prolifically until his death in 1992 reflect what seems to have been his own troubled soul and perpetually disordered life. His style changed over the decades, becoming somewhat softer and less aggressively disturbing, suggesting that his demons may have gone into at least partial retreat. But could anyone capable of painting the screaming popes ever truly have lost touch with the abyss? Related content: The Brilliantly Nightmarish Art & Troubled Life of Painter Francis Bacon Francis Bacon on The South Bank Show: A Singular Profile of the Singular Painter William Burroughs Meets Francis Bacon: See Never-Broadcast Footage (1982) The “Dark Relics” of Christianity: Preserved Skulls, Blood & Other Grim Artifacts The Scream Explained: What’s Really Happening in Edvard Munch’s World-Famous Painting Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Thursday, September 11th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

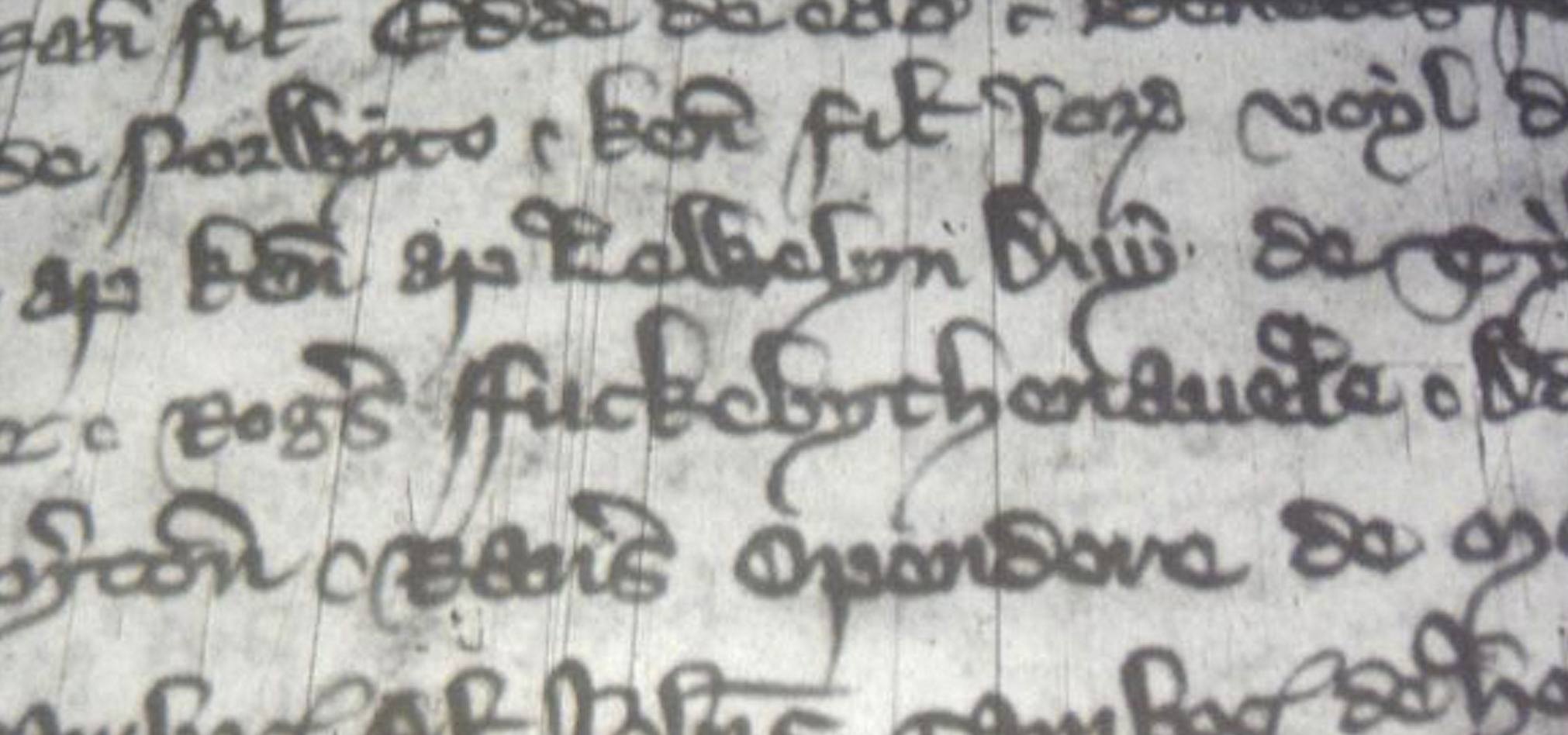

| 9:00 am | The Earliest Known Appearance of the F‑Word (1310)

Photo by Paul Booth You value decorum, propriety, eloquence, you treasure le mot juste and agonize over diction as you compose polite but strongly-worded letters to the editor. But alas, my literate friend, you have the misfortune of living in the age of Twitter, Tumblr, et al., where the favored means of communication consists of readymade mimetic words and phrases, photos, videos, and animated gifs. World leaders trade insults like 5th graders—some of them do not know how to spell. Respected scientists and journalists debate anonymous strangers with cartoon avatars and work-unsafe pseudonyms. Some of them are robots. What to do? Embrace it. Insert well-placed profanities into your communiqués. Indulge in bawdiness and ribaldry. You may notice that you are doing no more than writers have done for centuries, from Rabelais to Shakespeare to Voltaire. Profanity has evolved right alongside, not apart from, literary history. T.S. Eliot, for example, knew how to go lowbrow with the best of them, and gets credit for the first recorded use of the word “bullshit.” As for another, even more frequently used epithet in 24-hour online commentary?—well, the word “F*ck” has a far longer history. Not long ago we alerted you to the first known use of the versatile obscenity in a 1528 marginal note scribbled in Cicero’s De Officiis by a monk cursing his abbot. Not long after this discovery, notes Medievalists.net, another scholar found the word in a 1475 poem called Flen flyys. This was thought to be the earliest appearance of “f*ck” as a purely sexual reference until medieval historian Paul Booth of Keele University discovered an instance dating over a hundred years earlier. Rather than within, or next to, a work of literature, however, the word appears in a set of 1310 English court records. And no, it is decidedly not a legal term. The documents concern the case of “a man named Roger Fuckebythenavele.” Used three times in the record, the name, says Booth, is probably not a joke made by the scribe but some kind of bizarre nickname, though one hopes not a description of the crime. “Either it refers to an inexperienced copulator, referring to someone trying to have sex with a navel,” says Booth, stating the obvious, “or it’s a rather extravagant explanation for a dimwit, someone so stupid they think that this is the way to have sex.” Our medieval gent had other problems as well. He was called to court three times within a year before being pronounced “outlawed,” which The Independent’s Loulla-Mae Eleftheriou-Smith suggests execution but probably refers to banishment. For the word to have such casually hilarious or insulting currency in the early 14th century, it must have come from an even earlier time. Indeed, “f*ck is a word of German origin,” notes Jesse Sheidlower, author of an etymological history called The F Word, “related to words in several other Germanic languages, such as Dutch, German, and Swedish, that have sexual meanings as well as meaning such as ‘to strike’ or ‘to move back and forth’” (naturally). So, in other words, it’s just a word. But in this case it might have also been a weapon, Booth speculates, wielded “by a revengeful former girlfriend. Fourteenth-century revenge porn perhaps…” If that’s not evidence for you that the present may not be unlike the past, then maybe take note of the appearance of the word “twerk” in 1820. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017. Related Content: People Who Swear Are More Honest Than Those Who Don’t, Finds a New University Study Steven Pinker Explains the Neuroscience of Swearing (NSFW) Stephen Fry, Language Enthusiast, Defends The “Unnecessary” Art Of Swearing Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | The Technology That Brought Down Medieval Castles and Changed the Middle Ages Civilization moved past the use of castles long ago, but their imagery endures in popular culture. Even young children here in the twenty-twenties have an idea of what castles look like. But why do they look like that? Admittedly, that’s a bit of a trick question: the popular concept of castles tends to be inspired by medieval examples, but in historical fact, the design of castles changed substantially over time, albeit slowly at first. You can hear that process explained in the Get to the Point video above, which tells the story of “star forts,” the built response to the “technology that ended the Middle Ages.” You may be familiar with the concept of “motte and bailey,” now most widely understood as a metaphor for a certain debate tactic irritatingly prevalent on the internet. But it actually refers to a style of castle constructed in Europe between the tenth and the thirteenth centuries, consisting of a fortified hilltop keep, or “motte,” with a less defensible walled courtyard, or “bailey,” below. In case of an attack, the battle could primarily take place down in the bailey, with retreats to the motte occurring when strategically necessary. The motte-and-bailey castle is a “great idea,” says the video’s narrator, provided “you don’t have cannons shooting at you.” Castles, he explains, “were a reflection of armies at the time: build a big wall, keep the barbarians out.” But once the cannon came on the scene, those once-practically impervious stone walls became a serious liability. That was definitively proven in 1453, when “the Ottomans famously battered down the great walls of Constantinople with their cannons. That brought an end not only to the 1500-year-old Roman Empire, but also to the Middle Ages as an era entirely.” In response, castle architects added dirt slopes, or glacis, at the edges, as well as circular bastions to deflect cannon fire at the corners — which, inconveniently, created “dead zones” in which enemy soldiers could hide, protected from any defenses launched from within the castle. The solution was to make the bastions triangular instead, and then to add further triangular structures between them. Seen from the side, castles became much lower and wider; from above, they grew ever pointier and more complex in shape. Sébastien Le Prestre, Marquis of Vauban, an army officer under Louis XIV, became the acknowledged master of this form, the trace italienne. You may not know his name, but his designs made France “literally impossible to invade.” For sheer beauty, however, it would be hard to top the plans for star forts to defend Florence in the fifteen-twenties by a multi-talented artist named Michelangelo. Perhaps you’ve heard of him? Related Content: Leonardo da Vinci Draws Designs of Future War Machines: Tanks, Machine Guns & More How to Build a 13th-Century Castle, Using Only Authentic Medieval Tools & Techniques A Forgotten 16th-Century Manuscript Reveals the First Designs for Modern Rockets Behold a 21st-Century Medieval Castle Being Built with Only Tools & Materials from the Middle Ages Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Wednesday, September 10th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | How Erik Satie Invented Modern Music: A Visual Explanation Once you hear Erik Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, you never forget it. Not that popular culture would let you forget it: the piece has been, and continues to be, reinterpreted and sampled by musicians working in a variety of genres from pop to electronic to metal. In versions that sound close to what Satie would have intended when he composed it in 1888, it’s also been featured in countless films and television shows. It’s even heard with some frequency in YouTube videos, though in the case of the one from The Music Professor above, it’s not just the soundtrack, but also the subject. Using an annotated score, it explains just what makes the piece so enduring and influential. Upon “a simple iambic rhythm with two ambiguous major 7th chords,” Gymnopédie No. 1 introduces a melody that “floats above an austere procession of notes,” then “moves down the octave from F# to F#.” With its lack of a clear key, as well as its lack of development and drama that the orchestral music of the day would have trained listeners to expect, the piece was “as shocking as the dance of naked Spartans it was meant to evoke.” The melody makes its turns, but never quite arrives at its seeming destinations, going around in circles instead — before, all of a sudden, swerving into the “minor and dissonant” before ending in “profound melancholy.” Despite music in general having long since assimilated the daring qualities of Gymnopédie No. 1, the original piece still catches our ears — in its subtle way — whenever it comes on. So, in another way, do the less recognizable and more experimental Gnossiennes with which Satie followed them up. In the video above, the Music Professor provides a visual explanation of Gnossienne No. 1, during whose performance “soft dissonance hangs in the air” while “a curious melody floats over gentle syncopations in the left hand” over just two chords. The score comes with “surreal comments”: “Très luisant,” “Du bout de la pensée,” “Postulez en vous-même,” “Questionez.” Satie is often credited with pioneering what would become ambient music; could these be proto-Oblique Strategies? Related Content: Watch Animated Scores of Eric Satie’s Most Famous Pieces: “Gymnopedie No. 1” and “Gnossienne No. 1” Listen to Never-Before-Heard Works by Erik Satie, Performed 100 Years After His Death The Velvet Underground’s John Cale Plays Erik Satie’s Vexations on I’ve Got a Secret (1963) How Erik Satie’s “Furniture Music” Was Designed to Be Ignored and Paved the Way for Ambient Music Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

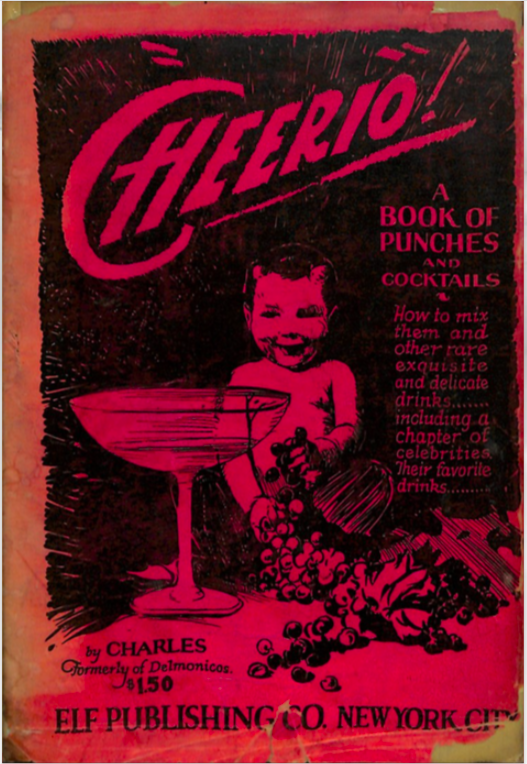

| 8:00 am | Browse Thousands of Free Vintage Cocktail Recipes Online (1705–1951)

Where do the hipster mixologists of Tokyo, Mexico City and Brooklyn take their inspiration? If not from the Exposition Universelle des Vins et Spiritueux’ free collection of digitized vintage cocktail recipe books, perhaps they should start. An initiative of the Museum of Wine and Spirits on the Ile de Bendor in Southeastern France, the collection is a boon to anyone with an interest in cocktail culture …ditto design, illustration, evolving social mores… 1928’s Cheerio, a Book of Punches and Cocktails was written by Charles, formerly of Delmonico’s, touted in the introductory note as “one who has served drinks to Princes, Magnates and Senators of many nations”. No doubt discretion prevented him from publishing his surname. Charles apparently abided by the theory that it’s five o’clock somewhere, with drinks geared to various times of day, from the moment you “stagger out of bed, groggy, grouchy and cross-tempered” (try a Charleston Bracer or a Brandy Port Nog) to the midnight hour when “insomnia, bad dreams, disillusionment and despair” call for such remedies as a Cholera Cocktail or an Egg Whiskey Fizz. As noted on the cover, there’s a section devoted to favorite recipes of celebrities. These bigwigs’ names will likely mean nothing to you nearly one hundred years later, but their first person reminiscences bring them roaring back to theatrical, boozy life. Here’s celebrated vaudevillian Trixie Friganza:

Indeed. Presumably any cocktail recipe in the EUVS’s vast collection could be adapted as a mocktail, but Charles gives a deliberate nod to Prohibition with a section on alcohol-free (and extremely easy to prepare) Temperance Drinks. Don’t expect a Shirley Temple — the triple threat child star was but an infant when Cheerio was published. Expand your options with a Saratoga Cooler or an Oggle Noggle instead.

Before attempting to recite the poem that opens 1949’s Bottoms Up: A Guide to Pleasant Drinking, you may want to slam a couple of Depth Bombs Cocktails or a Merry Widow Cocktail No. 1. In an abstemious condition, there’s no way this ditty can be made to scan…or rhyme:

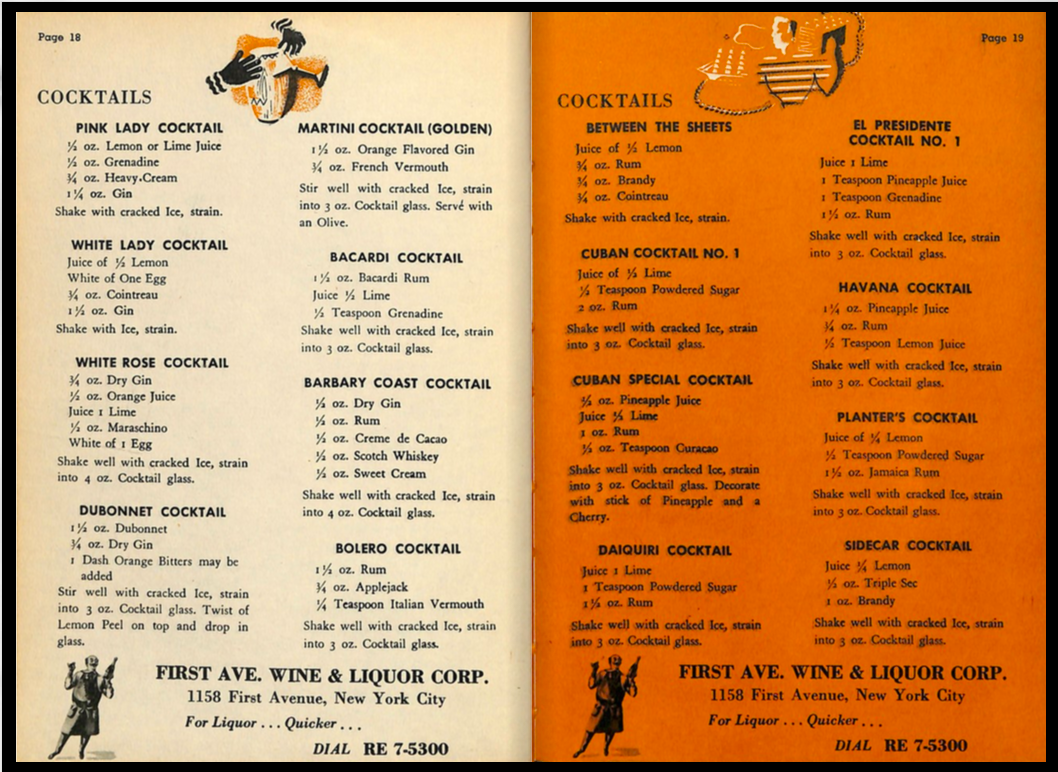

The cocktail recipes are solid, throughout, however, as one might expect from a book that doubled as an ad for sponsor First Avenue Wine and Liquor Corporation — “for Liquor…Quicker.” We’ve yet to try anything from the “wines in cookery” section — but suspect that sturdy fare like Potato Soup and Baked Beans could help sop up some of the alcohol, even if contains some hair of the dog…

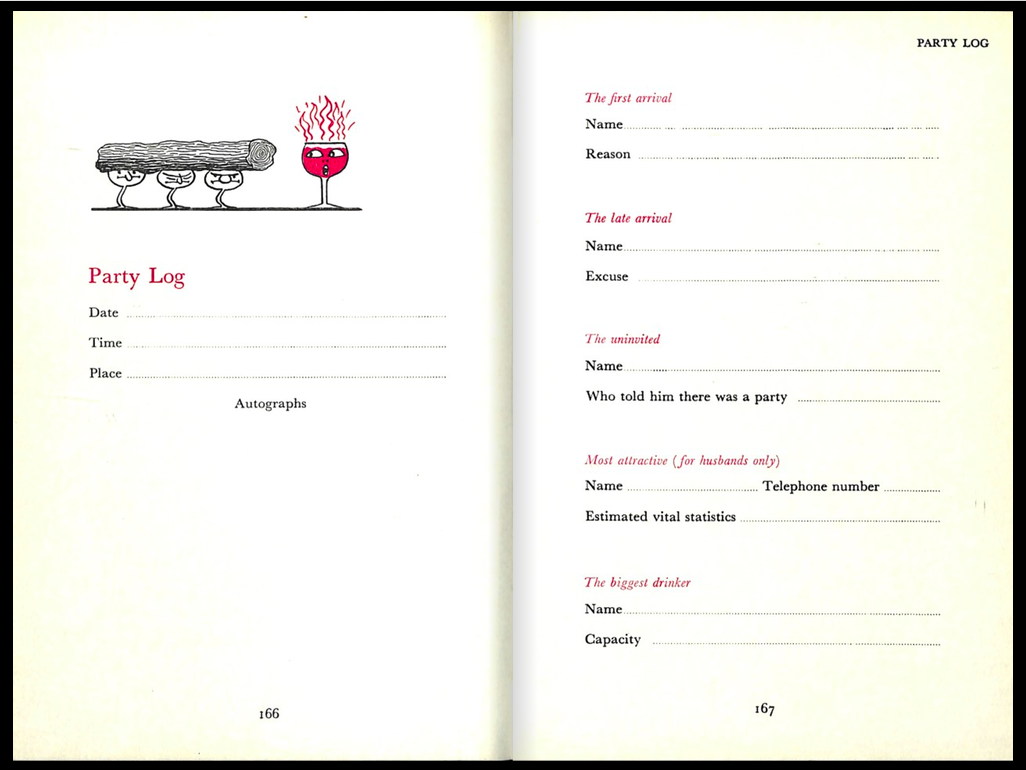

Shaking in the 60’s author Eddie Clark’s previous titles include Shaking with Eddie, Shake Again with Eddie and 1954’s Practical Bar Management. Clark, who served as head bartender at London’s Savoy Hotel, Berkeley Hotel and Albany Club, gets in the swinging 60s spirit, by dedicating this work to “all imbibing lovers.” William S. McCall’s decidedly boozy illustrations of elephants, anthropomorphized cocktail glasses and scantily clad ladies contribute to the festive atmosphere, though you probably won’t be surprised to learn that some of them have not aged well. Shaking in the 60’s boasts dozens of straightforward cocktail recipes (the Beatnik the Bunny Hug and the Monkey Hugall feature Pernod), a surprisingly serious-minded section on wine, and a couple of pages devoted to non-alcoholic drinks. If your child turns up their nose at Clark’s Remain Sober, serve ‘em an Albermarle Pussycat. Clark also draws on his professional expertise to help home bartenders get a grip on measurement conversions, supply lists, and toasts. So confident is he in his ability to help readers throw a truly memorable party, he includes a dishy party log, that probably should be kept under lock and key after it’s been filled out. We imagine it would pair well with the Morning Mashie, another Pernod-based concoction dedicated to “all those entering the hangover class.”

Delve into the Exposition Universelle des Vins et Spiritueux’ free collection of digitized vintage cocktail recipe books from the 1820s through the 1960s here. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2021. Related Content: A Digital Library for Bartenders: Vintage Cocktail Books with Recipes Dating Back to 1753 Explore an Online Archive of 12,700 Vintage Cookbooks Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker. |

| Tuesday, September 9th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | The Advanced Technology of Ancient Rome: Automatic Doors, Water Clocks, Vending Machines & More Ancient Rome never had an industrial revolution. Granted, certain historians have objected now and again to that once-settled claim, gesturing toward large heaps of pottery discovered in garbage dumps and other such artifacts clearly produced in large numbers. Still, the fact remains that Ancient Rome never had an industrial revolution of the kind that fired up toward the end of the eighteenth century, but not due to a complete absence of the relevant technology. As explained in the new Lost in Time video above, Romans had witnessed the power of steam harnessed back in the first century — but they dismissed it as a novelty, evidently unable to see its power to transform civilization. That’s just one of a variety of examples of genuine high Roman technology featured in the video, many or all of which would seem implausible to the average viewer if inserted into a story set in ancient Rome. Take the set of automatic doors installed in a temple, triggered by a fire that heats an underground water tank, which in turn fills up a pot attached to a cable that — through a system of pulleys — throws them open. (When the fire cools down, the doors then shut again.) This was the work of the Greek-born inventor Hero of Alexandria, who would bear comparison in one sense or another with everyone from Rube Goldberg to Leonardo da Vinci. It was also Hero who came up with that early steam turbine, called the aeolipile. He came along too late, however, to take credit for the “self-healing” Roman concrete previously much-featured here on Open Culture, the material of buildings like the Pantheon, “still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world.” Another invention highlighted in the video comes from Alexandria, but well before Hero’s time, and even before that of the Roman Empire itself: the accurate water clock engineered by Ctesibius, whose underlying design remained influential in the Roman era. Hydraulic power was also used in Roman mills, which made possible complex factory systems, even in a civilization that never reached an industrial revolution proper. And if a Roman factory worker got thirsty at break time, maybe he could drop a coin into one of Hero’s wine vending machines. Related content: How the Ancient Romans Built Their Roads, the Lifelines of Their Vast Empire The Amazing Engineering of Roman Baths The Ancient Roman Dodecahedron: The Mysterious Object That Has Baffled Archaeologists for Centuries Archaeologists Discover an Ancient Roman Snack Bar in the Ruins of Pompeii Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | Discover the 100-Year-Old Self-Playing Violin, One of the Most Complex Music Players Ever Made At the 1910 World’s Exhibition in Brussels, Ludwig Hupfeld unveiled the Phonoliszt-Violina, an instrument once dubbed “the eighth wonder of the world.” A leading maker of automated instruments in Germany, Hupfeld built a company that produced everything from phonola push-up players to player pianos. In 1907 he created his most famous invention, the Phonoliszt-Violina. It featured three vertically mounted violins, each with a single active string, played by a rotating bow of 1,300 horsehairs. Meanwhile, pneumatic bellows pressed the strings according to perforated rolls. And a player piano could accompany the violins. Sold in upright home and commercial models, the Phonoliszt-Violina entertained patrons of upscale hotels, restaurants, and cafes, before gradually fading into obsolescence. The Wintergatan video above, along with the WelteMax video below, will give you a nice introduction to one of the most complex music players ever made. If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day. If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks! Related Content |

| Monday, September 8th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | What an 85-Year-Long Harvard Study Says Is the Real Key to Happiness We’ve long used the French word milieu in English, but not with quite the same range of meanings it has back in France. For example, French society (and especially the members of its older generations) explicitly recognizes the value of a milieu in the sense of the collected friends, acquaintances, and relations with whom one has regular and frequent contact. Keeping a good milieu is a key task for living a good life. Robert Waldinger doesn’t use the word in the new hour-long Big Think video above, but then, he comes from a different cultural background: he’s American, for one, a Harvard psychiatrist, and he also happens to be a Zen Buddhist priest. But he would surely agree wholeheartedly about the importance of the milieu to human happiness. As the fourth director of the long-term Harvard Study of Adult Development, which has been keeping an eye on the well-being of its subjects for more than 85 years now, Waldinger knows something about happiness. Early in the video, he cites findings that half of it is “a kind of biological set point,” 10 percent is “based on our current life circumstances,” and the remaining 40 percent is under our control. The single most important factor in the variability of our happiness, he explains, is our relationships. To take the measure of that aspect of our own lives, we should ask ourselves these questions: “Do I have enough connection in my life?” “Do I have relationships that are warm and supportive?” “What am I getting from relationships?” There are, of course, good relationships and bad relationships, those that fill you with energy and those that drain you of energy. To a great extent, Waldinger says, good relationships can be cultivated, and even bad relationships can be modified or approached in an advantageous way. What makes learning to do so important is that a lack of relationships — that is, loneliness — can take as much of a physical toll as obesity or heavy smoking. Alas, since television made its way into the home after the Second World War, we’ve lived with a rapidly and ceaselessly multiplying array of forces that make it difficult to form and maintain relationships; at this point, we’re so “constantly distracted by our wonderful screens” that we have trouble paying attention to even the people we think we love. This is where Zen comes in. Attention, as one of Waldinger’s own teachers in that tradition put it, is “the most basic form of love,” and meditation has always been a reliable way to cultivate it. Such a practice reveals our own minds to be “messy and chaotic,” and from that realization, it’s not far to the understanding that “everybody’s minds are messy and chaotic.” Attaining a clear view of our own questionable impulses and irritating deficiencies helps us to accept those same qualities in others. “We can sometimes imagine that other people have it all figured out, and we’re the only one who has ups and downs in our life,” says Waldinger, but the truth is that “everybody has ups and downs. We never figure it out, ultimately.” The fleeting nature of satisfaction constitutes just one facet of the impermanence Zen requires us to accept. Nothing lasts forever: certainly not our lives, nor those of the members of our milieu, so if we want to enjoy them, we’d better start paying attention to them while we still can. Related content: What Are the Keys to Happiness? Lessons from a 75-Year-Long Harvard Study How to Be Happier in 5 Research-Proven Steps, According to Popular Yale Professor Laurie Santos A 6‑Step Guide to Zen Buddhism, Presented by Psychiatrist-Zen Master Robert Waldinger All You Need is Love: The Keys to Happiness Revealed by a 75-Year Harvard Study How Much Money Do You Need to Be Happy? A New Study Gives Us Some Exact Figures How Loneliness Is Killing Us: A Primer from Harvard Psychiatrist & Zen Priest Robert Waldinger Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | Why You Should Only Work 3–4 Hours a Day, Like Charles Darwin, Virginia Woolf & Adam Smith These days, we hear much said on social media — surely too much — in favor of the “hustle culture” and the “grind mindset” (or, abbreviated for maximum efficiency, the “grindset”). Dedication to your work is to be admired, provided that the work itself is of value, but the more of a day’s hours you devote to it, the likelier returns are to diminish. Oliver Burkeman, a popular writer on productivity and time management, has made this point in a variety of ways, usually returning to the same finding: look at the work habits of a range of luminaries including Charles Darwin, Henri Poincaré, Thomas Jefferson, Charles Dickens, Virginia Woolf, J.G. Ballard, Ingmar Bergman, Alice Munro, John le Carré, and Adam Smith, and you’ll find that they all put in about three or four hours of concentrated effort per day. “You almost certainly can’t consistently do the kind of work that demands serious mental focus for more than about three or four hours a day,” Burkeman writes on his site. If you do work of that kind, it would behoove you to “just focus on protecting four hours — and don’t worry if the rest of the day is characterized by the usual scattered chaos.” Doing so entails making an “internal psychological move: to give up demanding more of yourself than three or four hours of daily high-quality mental work.” You’ll also finally have to “abandon the delusion that if you just managed to squeeze in a bit more work, you’d finally reach the commanding status of feeling ‘in control’ and ‘on top of everything’ at last.” The “the truly valuable skill here,” Burkeman continues, “isn’t the capacity to push yourself harder, but to stop and recuperate despite the discomfort of knowing that work remains unfinished, emails unanswered, other people’s demands unfulfilled.” This is easier said than done, of course, but any attempt to implement what Burkeman calls the “three-to-four-hour rule” must begin with a bit of trial and error: about when best in the day to schedule those hours, but also about how best to eliminate distractions during those hours. Underneath all this lies the need to accept life’s finitude, as Burkeman explains in the interview at the top of the post, with its implication that we can only get so much done in what he often describes as our allotted 4,000 weeks — minus however many thousand we’ve already lived so far. To think more about managing your time effectively, see Burkerman’s books: Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals and also Meditations for Mortals: Four Weeks to Embrace Your Limitations and Make Time for What Counts. Related Content: The Daily Routines of Famous Creative People, Presented in an Interactive Infographic Write Only 500 Words Per Day and Publish 50+ Books: Graham Greene’s Writing Method David Lynch Explains How Simple Daily Habits Enhance His Creativity Haruki Murakami’s Daily Routine: Up at 4:00 a.m., 5–6 Hours of Writing, Then a 10K Run Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Friday, September 5th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 5:43 am | Explore an Online Archive of 12,700 Vintage Cookbooks

“Early cookbooks were fit for kings,” writes Henry Notaker at The Atlantic. “The oldest published recipe collections” in the 15th and 16th centuries in Western Europe “emanated from the palaces of monarchs, princes, and grand señores.” Cookbooks were more than recipe collections—they were guides to court etiquette and sumptuous records of luxurious living. In ancient Rome, cookbooks functioned similarly, as the extravagant fourth century Cooking and Dining in Imperial Rome demonstrates. Written by Apicius, “Europe’s oldest [cookbook] and Rome’s only one in existence today”—as its first English translator described it—offers “a better way of knowing old Rome and antique private life.” It also offers keen insight into the development of heavily flavored dishes before the age of refrigeration. Apicius recommends that “cooks who needed to prepare birds with a ‘goatish smell’ should bathe them in a mixture of pepper, lovage, thyme, dry mint, sage, dates, honey, vinegar, broth, oil and mustard,” Melanie Radzicki McManus notes at How Stuff Works. Early cookbooks communicated in “a folksy, imprecise manner until the Industrial Revolution of the 1800s,” when standard (or metric) measurement became de rigueur. The first cookbook by an American, Amelia Simmons’ 1796 American Cookery, placed British fine dining and lavish “Queen’s Cake” next to “johnny cake, federal pan cake, buckwheat cake, and Indian slapjack,” Keith Stavely and Kathleen Fitzgerald write at Smithsonian, all recipes symbolizing “the plain, but well-run and bountiful American home.” With this book, “a dialogue on how to balance the sumptuous with the simple in American life had begun.” Cookbooks are windows into history—markers of class and caste, documents of daily life, and snapshots of regional and cultural identity at particular moments in time. In 1950, the first cookbook written by a fictional lifestyle celebrity, Betty Crocker, debuted. It became “a national best-seller,” McManus writes. “It even sold more copies that year than the Bible.” The image of the perfect Stepford housewife may have been bigger than Jesus in the 50s, but Crocker’s career was decades in the making. She debuted in 1921, the year of publication for another, more humble recipe book: the Pilgrim Evangelical Lutheran Church Ladies’ Aid Society of Chicago’s Pilgrim Cook Book. As Ayun Halliday noted in an earlier post, this charming collection features recipes for “Blitz Torte, Cough Syrup, and Sauerkraut Candy,” and it’s only one of thousands of such examples at the Internet Archive’s Cookbook and Home Economics Collection, drawn from digitized special collections at UCLA, Berkeley, and the Prelinger Library. When we last checked in, the collection featured 3,000 cookbooks. It has grown since 2016 to a library of 12,700 vintage examples of homespun Americana, fine dining, and mass marketing. Laugh at gag-inducing recipes of old; cringe at the pious advice given to women ostensibly anxious to please their husbands; and marvel at how various international and regional cuisines have been represented to unsuspecting American home cooks. (It’s hard to say whether the cover or the contents of a Chinese Cook Book in Plain English from 1917 seem more offensive.) Cookbooks of recipes from the American South are popular, as are covers featuring stereotypical “mammy” characters. A more respectful international example, 1952’s Luchow’s German Cookbook gives us “the story and the favorite dishes of America’s most famous German restaurant.” There are guides to mushrooms and “commoner fungi, with special emphasis on the edible varieties”; collections of “things mother used to make” and, most practically, a cookbook for leftovers. And there is every other sort of cookbook and home ec manual you could imagine. The archive is stuffed with helpful hints, rare ingredients, unexpected regional cookeries, and millions of minute details about the habits of these books’ first hungry readers. If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day. If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks! Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2020. Related Content: A Database of 5,000 Historical Cookbooks–Covering 1,000 Years of Food History–Is Now Online Discover the World’s Oldest Surviving Cookbook, De Re Coquinaria, from Ancient Rome The World’s Oldest Cookbook: Discover 4,000-Year-Old Recipes from Ancient Babylon Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. |

| Thursday, September 4th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | How Egon Schiele Made Enduring Art from His Troubled Life and Times “May you live in interesting times,” goes the apocryphal but nevertheless much-invoked “Chinese curse.” Egon Schiele, born in the Austria-Hungary of 1890, certainly did live in interesting times, and his work, as featured in the new Great Art Explained video above, can look like the creations of a cursed man. That’s especially true of those of his many self-portraits that, as host James Payne puts it, render his own body “more emaciated than it actually was, radically distorted and twisted, sometimes faceless or limbless, sometimes in abject terror.” Here Schiele worked at “an intersection of suffering and sex, as if he is disgusted by his own body.” Such a preoccupation, as Payne suggests, may not seem completely unreasonable in a man who witnessed his own father’s death from syphilis — caught from a prostitute, on the night of his wedding to Schiele’s mother — when he was still in adolescence. But what tends to occupy most discussions of Schiele’s art is less his familial or psychological background than his line: the “thin line between beauty and suffering” that clearly obsessed him, yes, but also the line created by the hand with which he drew and painted. His art remains immediately recognizable today because “his line has a particular rhythm: angular, tense, and economically placed. It’s not just a means of describing form; it’s a voice.” In this voice, Schiele composed not likenesses but “psychological portraits, a search for the self or the ego, a preoccupation of the time.” The figure of Sigmund Freud loomed large over fin-de-siècle Vienna, of course, and into the twentieth century, the city and its civilization were “caught between the old imperial order and modern democratic movements.” A “laboratory for psychoanalysis, radical art, music, and taboo-breaking literature,” Vienna had also given rise to the career of Schiele’s mentor Gustav Klimt. By the time Schiele hit his stride, he could express in his work “not just personal discomfort, but the sickness and fragility of an entire society” — before he fell victim to the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 at just 28 years old, along with his wife and unborn child. In a sense, he was unlucky to live when and where he did. But as his art also reminds us, we don’t merely inhabit our time and place; we’re created by them. Related Content: Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

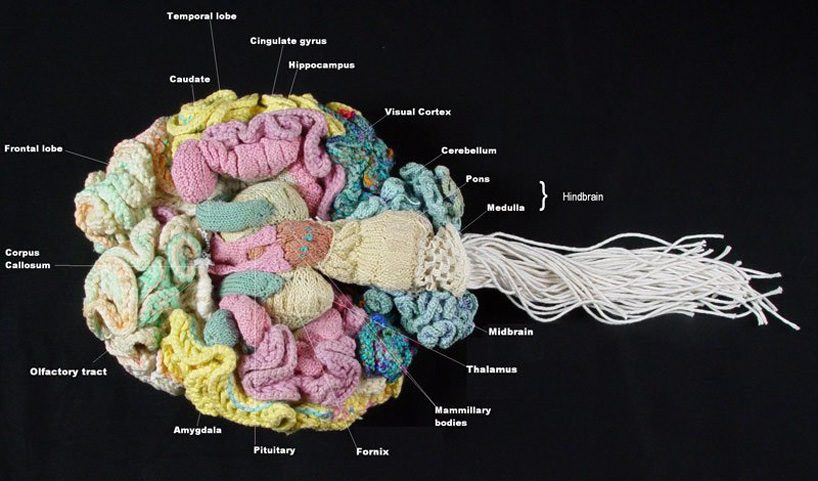

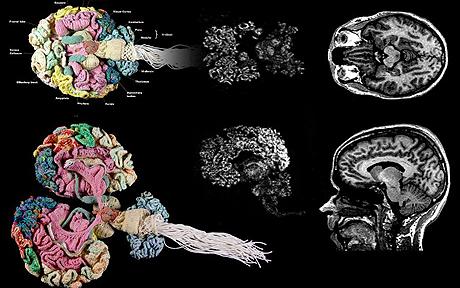

| 8:00 am | Behold an Anatomically Correct Replica of the Human Brain, Knitted by a Psychiatrist

Our brains dictate our every move. They’re the ones who spur us to study hard, so we can make something of ourselves, in order to better our communities. They name our babies, choose our clothes, decide what we’re hungry for. They make and break laws, organize protests, fritter away hours on social media, and give us the green light to binge watch a bunch of dumb shows when we could be reading War and Peace. They also plant the seeds for Fitzcarraldo-like creative endeavors that take over our lives and generate little to no income. We may describe such endeavors as a labor of love, into which we’ve poured our entire heart and soul, but think for a second. Who’s really responsible here? The heart, that muscular fist-sized Valentine, content to just pump-pump-pump its way through life, lub-dub, lub-dub, from cradle to grave? Or the brain, a crafty Iago of an organ, possessor of billions of neurons, complex, contradictory, a mystery we’re far from unraveling? Psychiatrist Dr. Karen Norberg’s brain has steered her to study such heavy duty subjects as the daycare effect, the rise in youth suicide, and the risk of prescribing selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors as a treatment for depression.

On a lighter note, it also told her to devote nine months to knitting an anatomically correct replica of the human brain. (Twelve, if you count three months of research before casting on.) How did her brain convince her to embark on this madcap assignment? Easy. It arranged for her to be in the middle of a more prosaic knitting project, then goosed her into noticing how the ruffles of that project resembled the wrinkles of the cerebral cortex. Coincidence? Not likely. Especially when one of the cerebral cortex’s most important duties is decision making. As she explained in an interview with The Telegraph, brain development is not unlike the growth of a knitted piece:

Dr. Norberg—who, yes, has on occasion referred to her project as a labor of love—told Scientific American that such a massive crafty undertaking appealed to her sense of humor because “it seemed so ridiculous and would be an enormously complicated, absurdly ambitious thing to do.” That’s the point at which many people’s brains would give them permission to stop, but Dr. Norberg and her brain persisted, pushing past the hypothetical, creating colorful individual structures that were eventually sewn into two cuddly hemispheres that can be joined with a zipper. (She also let slip that her brain—by which she means the knitted one, though the observation certainly holds true for the one in her head—is female, due to its robust corpus callosum, the “tough body” whose millions of fibers promote communication and connection.) Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019. Related Content: The Human Brain: A Free Online Course from MIT Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker. |

| Wednesday, September 3rd, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | The World’s Most Famous Organ Piece Played on the World’s Largest Fully Operational Pipe Organ The world’s most famous organ piece, played on the world’s largest fully functioning pipe organ. That’s what you have above. Here, organist Dylan David Shaw performs Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D minor on the famous Wanamaker organ. Originally built for the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, the organ ended up in Philadelphia’s Wanamaker’s department store in 1911. More than a century later, the organ still resides in the same store. But Macy’s eventually took over Wanamaker’s, and Macy’s now plans to close the store, leaving the fate of the organ unknown. Where will the 28,000-pipe organ find a new home? That’s still TBD, something that’s likely to get resolved in the months to come. Related Content Download the Complete Organ Works of J.S. Bach for Free |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | Hear the First Masterpiece of Electronic Music, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Gesang der Jünglinge Karlheinz Stockhausen appears, among many other cultural figures, on the cover of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. His inclusion was more than a trendy gesture toward the European avant-garde; anyone who knows that pathbreaking electronic composer’s work will notice its influence on the album at first listen. Paul McCartney himself went on record with his notion that assuming the alter egos of the title would allow him and his fellow Beatles to branch out both culturally and intellectually in their music, incorporating pastiches of Ravi Shankar, B. B. King, Albert Ayler, the Doors, the Beach Boys, and indeed Stockhausen, whose Gesang der Jünglinge had already inspired “Tomorrow Never Knows” on Revolver. Literally “Song of the Youths,” Gesang der Jünglinge was an early work for Stockhausen, who composed it in 1954, when he was still a PhD student in communications at the University of Bonn. Inspired by not just his technological interests but also his devout Catholicism, he decided to create a mass for electronic sounds and voices, with the intent to debut it at Cologne Cathedral. (Legend has it that he was rebuffed by religious authorities, who insisted that loudspeakers had no place in a house of worship, but sources disagreed on whether he actually sought their permission in the first place.) He drew its words from a passage of the Old Testament story of three boys cast into the fire by King Nebuchadnezzar for their refusal to worship a golden idol and kept unharmed by the praise to God they sang amid the flames. In Stockhausen’s high-tech rendering, the boys are represented by the voice of twelve-year-old Josef Protschka (who would grow up to become an acclaimed vocalist in his own right), and the fire by a collage of electronic sounds. Though the composer’s manipulations, part design and part chance, the human and mechanical halves of the piece become one: Protschka’s vocals break apart and reform into fragments of language never before heard, and the artificially generated tones bend uncannily toward the sound of sung vowels. All this, to say nothing of its playback in five-channel sound in a time when stereo was still a novelty, would have sounded deeply, even disturbingly unfamiliar to the audience at Gesang der Jünglinge’s premiere — and its impact probably hadn’t been much diminished by the time of the 2001 performance above. Stockhousen’s music may have been after the shock of the new, but it also faced the eternal. Related content: Hear Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Pioneering Compositions for Music Boxes A Karlheinz Stockhausen Branded Car: A Playful Tribute to the Groundbreaking Electronic Composer “Tomorrow Never Knows”: How The Beatles Invented the Future With Studio Magic, Tape Loops & LSD The History of Electronic Music in 476 Tracks (1937–2001) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Tuesday, September 2nd, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | How Raphael Became A Master: Watch the Evolution of the Artist Through His Madonna Paintings No artist became a Renaissance master through a single piece of work, though now, half a millennium later, that may be how most of us identify them. Leonardo? Painter of the Mona Lisa. Michelangelo? Painter of the Sistine Chapel ceiling (or, perhaps, the sculptor of the most famous David, depending on your medium of choice). Raphael? Painter of The School of Athens, as recently featured here on Open Culture. Raphael painted that masterwork in Vatican City’s Apostolic Palace between the years 1509 and 1511, when he was in his mid-twenties. Understanding how he could have attained that level of skill by that age requires examining his other work, as Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, does in the new video above. Specifically, Puschak examines Raphael’s Madonnas, a subject to which he returned over and over again throughout the course of his short but productive career. In what seems to have been his first rendition of Mary and her holy son, Puschak says, “you can see that Raphael has a better sense of three-dimensional bodies and how to make them feel like they’re part of the space that they’re in” than his father, who’d been a well-regarded painter himself, or even than Piero della Francesca, from whom his father learned. “Yet the painting also suffers from “an awkwardness in the arrangement of the figures,” as well as a lack of “emotion, relationships, or any sense of narrative” — much like “a thousand other Madonnas that came before.” Yet Raphael was a quick study, a trait reflected in the development of the many Madonnas he painted thereafter. From Leonardo he learned techniques like sfumato, the creation of soft transitions between colors; from Michelangelo, “how to use the human body as an expressive tool.” But what most clearly emerges is the concept contemporary theorist Leon Battista Alberti called historia: a narrative that plays out even within the confines of a static image. In Raphael’s circular, abundantly detailed Alba Madonna of 1511, Puschak sees the infant Jesus “not so much taking as grabbing his future and pulling it closer” as Mary looks on with emotions subtly layered into her face. How, exactly, Raphael honed his instinct for drama is a question for art historians. But would it be too much of a reach to guess that he also learned a thing or two from his time as a stage-set designer? Related content: Artist Turns Famous Paintings, from Raphael to Monet to Lichtenstein, Into Innovative Soundscapes Why Leonardo da Vinci’s Greatest Painting is Not the Mona Lisa The Evolution of Kandinsky’s Painting: A Journey from Realism to Vibrant Abstraction Over 46 Years Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose.