Add this feed to your friends list for news aggregation, or view this feed's syndication information.

LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose.

| Monday, September 29th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | Carl Sagan’s Baloney Detection Kit: Tools for Thinking Critically & Knowing Pseudoscience When You See It Though he died too young, Carl Sagan left behind an impressively large body of work, including more than 600 scientific papers and more than 20 books. Of those books, none is more widely known to the public — or, still, more widely read by the public — than Cosmos, accompanied as it was by Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, a companion television series on PBS. Sagan’s other popular books, like Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors or Contact (the basis of the 1997 Hollywood movie) are also well worth reading, but we perhaps ignore at our greatest peril The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. Published in 1995, the year before Sagan’s death, it stands as his testament to the importance of critical, scientific thinking for all of us. The Demon-Haunted World is the subject of the Genetically Modified Skeptic video above, whose host Drew McCoy describes it as his favorite book. He pays special attention to its chapter in which Sagan lays out what he calls his “baloney detection kit.” This assembled metaphorical box of tools for diagnosing fraudulent arguments and constructing reasoned ones involves these nine principles:

As McCoy points out, these techniques of mind have to do with canceling out the manifold biases present in our thinking, those natural human tendencies that incline us to accept ideas that may or may not coincide with reality as it is. If we take no trouble to correct for these biases, Sagan came to believe, we’ll become easy marks for all the tricksters and charlatans who happen to come our way. And that’s just on the micro level: on the macro level, vulnerability to delusion can bring down entire civilizations. “Like all tools, the baloney detection kit can be misused, applied out of context, or even employed as a rote alternative to thinking,” Sagan cautions. “But applied judiciously, it can make all the difference in the world — not least in evaluating our own arguments before we present them to others.” McCoy urges us to heed these words, adding that “this kit is not some perfect solution to the world’s problems, but as it’s been utilized over the last few centuries” — for its basic precepts long predate Sagan’s particular articulation — “it has enabled us to create technological innovations and useful explanatory models of our world more quickly and effectively than ever before.” The walls of baloney may always be closing in on humanity, but if you follow Sagan’s advice, you can at least give yourself some breathing room. Related content: Carl Sagan on the Importance of Choosing Wisely What You Read (Even If You Read a Book a Week) Carl Sagan’s Syllabus & Final Exam for His Course on Critical Thinking (Cornell, 1986) Richard Feynman Creates a Simple Method for Telling Science From Pseudoscience (1966) How to Spot Bullshit: A Manual by Princeton Philosopher Harry Frankfurt (RIP) Critical Thinking: A Free Course Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | Meryl Streep’s First Film Role Was in an Animated Film on Erik Erikson’s Stages of Life (1976) Difficult as it may be to remember now, there was a time when Meryl Streep was not yet synonymous with silver-screen stardom — a time, in fact, when she had yet to appear on the silver screen at all. Half a century ago, she was just another young stage actress in New York, albeit one rapidly ascending the rungs of theatrical prestige, doing three Shakespeare plays and then starring in Weill, Hauptmann, and Brecht’s Happy End on Broadway. The Deer Hunter, Kramer vs. Kramer, Out of Africa, Postcards from the Edge, The Bridges of Madison County: all this lay in her future in 1976, the year of her feature debut. Streep made that debut in Everybody Rides the Carousel, a now-obscure animated film that dramatizes post-Freudian psychologist Erik Erikson’s eight stages of psychosocial development. First published in his book Childhood and Society in 1950, this scheme captured the imagination of the mid-century American public, growing ever hungrier as it was for clear, legible systems of self-understanding. Erikson conceived of each age of man as a struggle for resolution between two opposing forces: in infancy, for example, trust versus mistrust; in adolescence, identity versus role confusion; and so on. The young Meryl Streep, or rather her voice, appears in the sixth stage, early adulthood, whose theme is love. She acts out that age’s contest of intimacy and isolation with Charles Levin, another up-and-comer who would go on to achieve wide recognition on television shows like Alice, Hill Street Blues, and (just once, but memorably) Seinfeld. In character as a young couple unsteadily feeling their way through their relationship, the two engage in a remarkably naturalistic conversation, all animated in a seventies watercolor style in the vision of director John Hubley. A prolific animator who’d worked on Disney’s Fantasia, Hubley was known as the creator of Mr. Magoo: a man who provided us all with an example of how to navigate late adulthood’s path between ego integrity and despair, however myopically. via Messy Nessy Related content: Watch Meryl Streep Have Fun with Accents: Bronx, Polish, Irish, Australian, Yiddish & More Master of Light: A Close Look at the Paintings of Johannes Vermeer Narrated by Meryl Streep Marcel Marceau Mimes the Progression of Human Life, From Birth to Death, in 4 Minutes Meryl Streep Gives Graduation Speech at Barnard Hear Meryl Streep Read Sylvia Plath’s “Morning Song,” a Poem Written After the Birth of Her Daughter Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Thursday, September 25th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | A Tour of the New David Bowie Archive Featuring 90,000 Artifacts from His Life & Career With the tenth anniversary of David Bowie’s death coming up early next year, more than a few fans will have their minds on a pilgrimage to mark the occasion. Perhaps with that very time frame in mind, the V&A East Storehouse in London has just opened the David Bowie Center. Run by the Victoria and Albert Museum, to which Bowie left an archive of about 90,000 of his possessions, this new institution will show a few hundred of those artifacts at a time, and even make a range of them available on request to visitors. As for what exactly is in there, Jessica the Museum Guide makes a brief survey of the Bowieana currently on display in the video above. Some of the featured objects, like the suits Bowie wore in his videos for “Life on Mars?” and “Let’s Dance” or the crystal ball he held aloft as Jareth the Goblin King in Labyrinth, may well be recognizable even to casual Bowie appreciators. Longer-term fans will surely recognize the outlandish but elegant Kansai Yamamoto-designed costumes that visually defined personae like Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane, the Alexander McQueen-designed Union Jack frock from the cover of Earthling, and perhaps even the metal angel wings Bowie donned onstage during the highly ambitious but much-derided Glass Spider Tour of the late nineteen-eighties. Going deeper, there’s also the Stylophone, a kind of toy electronic instrument from the late sixties, that Bowie used on “Space Oddity” (and had to repurchase on eBay); the much more professional-grade EMS suitcase synthesizer given to him by Brian Eno, which he used on the “Berlin trilogy” albums they made together; the personal deck of Oblique Strategies, co-created by Eno, that shows signs of intensive use in Bowie’s own creative process; his correspondence with Let’s Dance producer Nile Rodgers (a curator of the Bowie Center’s current exhibition), about their second album Black Tie White Noise; and materials from Omikron: The Nomad Soul, the computer game to which he contributed music as well as a digitized performance in the late nineties. The collection that Bowie donated to the V&A already came carefully organized and cataloged, which shows a meticulousness uncommon to rock stars, and a deliberateness about not just cultivating his public image at any given cultural moment, but also actively curating the materials of his own historical narrative. It seems Bowie always had one eye on the past: his own, of course, but also more distant eras, rich with disused aesthetics to revive and make his own. The other eye he kept on the future, especially as the internet was growing into a cultural force. The David Bowie Center has his personal notes on the subject, which include a reference to BowieNet, the internet service provider he founded around the turn of the millennium. BowieNet is now long gone, of course, but Bowie’s legacy — especially now that it’s been institutionally enshrined and made so accessible to the public — will outlast us all. Related Content: The Art Collection of David Bowie: An Introduction Meet the Memphis Group, the Bob Dylan-Inspired Designers of David Bowie’s Favorite Furniture The Musical Career of David Bowie in One Minute … and One Continuous Take Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 10:00 am | The Gilded Age: A Free Historical Documentary That Helps Make Sense of Our Own Fraught Times Ever-increasing economic inequality, rapid technological change, the creation of dominant corporations controlled by a small business elite, politicians in the pocket of big business leaders, and the rise of populism and nativism. These are all features of American life in 2025. But our nation has also seen this movie play before, most notably back in the Gilded Age, which ran from the 1870s through the late 1890s. Above, we have a free two-hour documentary on the Gilded Age created by PBS. They write:

To a certain degree, this documentary will help you make better sense of our own fraught times and perhaps feel more optimistic about where we might end up. (It’s worth keeping in mind that the disruptions of the Gilded Age eventually gave way to the reforms of the Progressive Era.) What’s more, if you’re watching the excellent HBO series, The Gilded Age, the film provides historical background that will directly add to your appreciation of the show. You can watch the film online above, or find it in our collection of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More. If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day. If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

|

| Wednesday, September 24th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

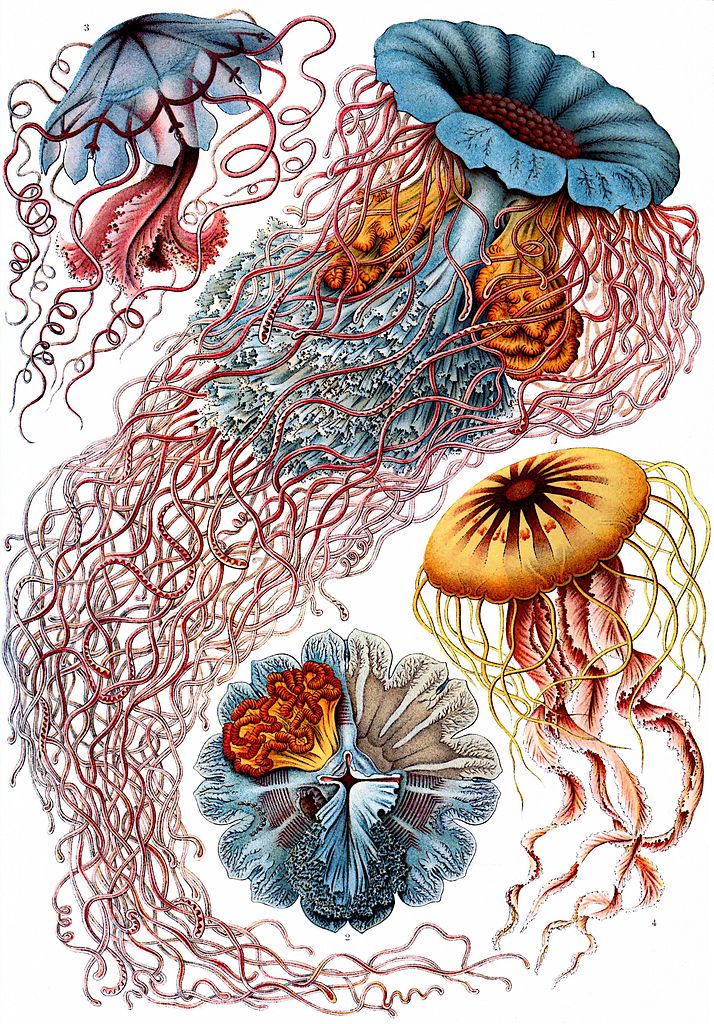

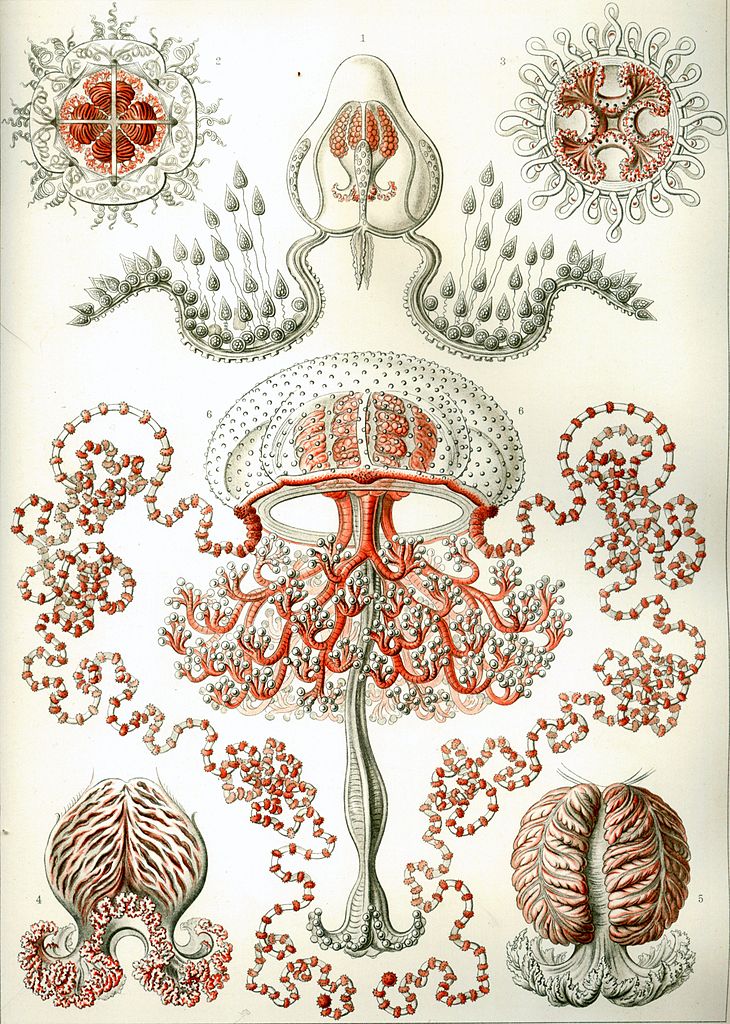

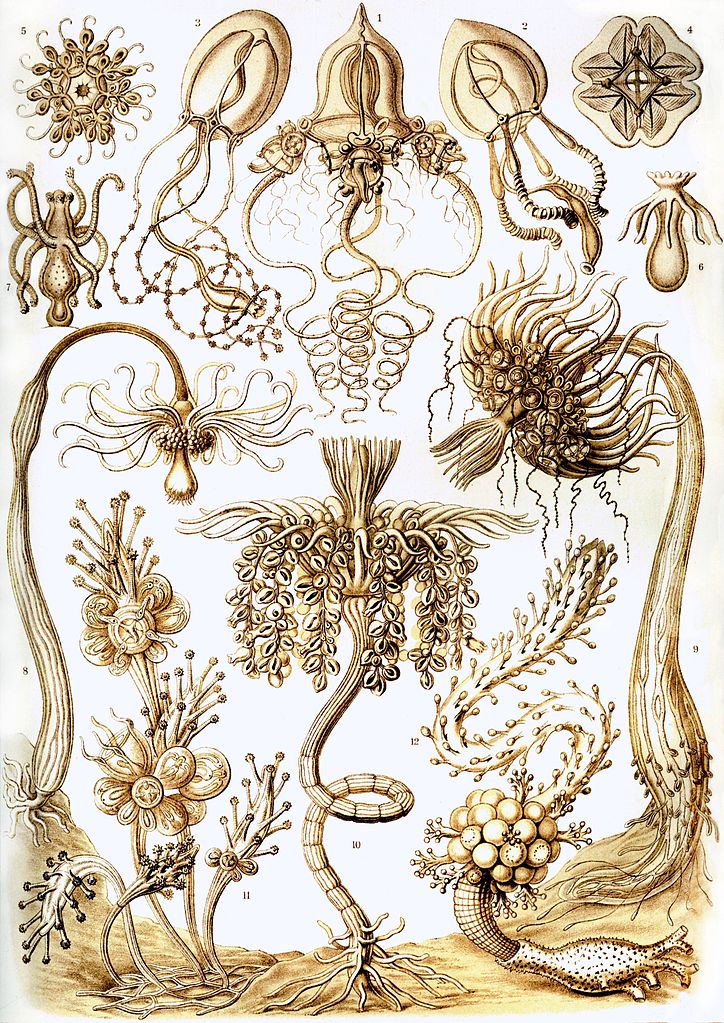

| 9:00 am | Ernst Haeckel’s Sublime Drawings of Flora & Fauna: The Beautiful Scientific Drawings That Influenced Europe’s Art Nouveau Movement (1889)

If you follow the ongoing beef many popular scientists have with philosophy, you’d be forgiven for thinking the two disciplines have nothing to say to each other. That’s a sadly false impression, though they have become almost entirely separate professional institutions. But during the first, say, 200 years of modern science, scientists were “natural philosophers”—often as well versed in logic, metaphysics, or theology as they were in mathematics and taxonomies. And most of them were artists too of one kind or another. Scientists had to learn to draw in order to illustrate their findings before mass-produced photography and computer imaging could do it for them. Many scientists have been fine artists indeed, rivaling the greats, and they’ve made very fine musicians as well.

And then there’s Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, a German biologist and naturalist, philosopher and physician, and proponent of Darwinism who described and named thousands of species, mapped them on a genealogical tree, and “coined several scientific terms commonly known today,” This is Colossal writes, “such as ecology, phylum, and stem cell.” That’s an impressive resume, isn’t it? Oh, and check out his art—his brilliantly colored, elegantly rendered, highly stylized depictions of “far flung flora and fauna,” of microbes and natural patterns, in designs that inspired the Art Nouveau movement. “Each organism Haeckel drew has an almost abstract form,” notes Katherine Schwab at Fast Co. Design, “as if it’s a whimsical fantasy he dreamed up rather than a real creature he examined under a microscope. His drawings of sponges reveal their intensely geometric structure—they look architectural, like feats of engineering.”

Haeckel published 100 fabulous prints beginning in 1889 in a series of ten books called Kunstformen der Natur (“Art Forms in Nature”), collected in two volumes in 1904. The astonishing work was “not just a book of illustrations but also the summation of his view of the world,” one which embraced the new science of Darwinian evolution wholeheartedly, writes scholar Olaf Breidbach in his 2006 Visions of Nature. Haeckel’s method was a holistic one, in which art, science, and philosophy were complementary approaches to the same subject. He “sought to secure the attention of those with an interest in the beauties of nature,” writes professor of zoology Rainer Willmann in a book from Taschen called The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel, “and to emphasize, through this rare instance of the interplay of science and aesthetics, the proximity of these two realms.”

The gorgeous Taschen book includes 450 of Haeckel’s drawings, watercolors, and sketches, spread across 704 pages, and it’s expensive. But you can see all 100 of Haeckel’s originally published prints in zoomable high-resolution scans here. Or purchase a one-volume reprint of the original Art Forms in Nature, with its 100 glorious prints, through this Dover publication, which describes Haeckel’s art as “having caused the acceptance of Darwinism in Europe…. Today, although no one is greatly interested in Haeckel the biologist-philosopher, his work is increasingly prized for something he himself would probably have considered secondary.” It’s a shame his scientific legacy lies neglected, if that’s so, but it surely lives on through his art, which may be just as needed now to illustrate the wonders of evolutionary biology and the natural world as it was in Haeckel’s time.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017. Related Content Download 435 High Resolution Images from John J. Audubon’s The Birds of America Two Million Wondrous Nature Illustrations Put Online by The Biodiversity Heritage Library Cats in Japanese Woodblock Prints: How Japan’s Favorite Animals Came to Star in Its Popular Art Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

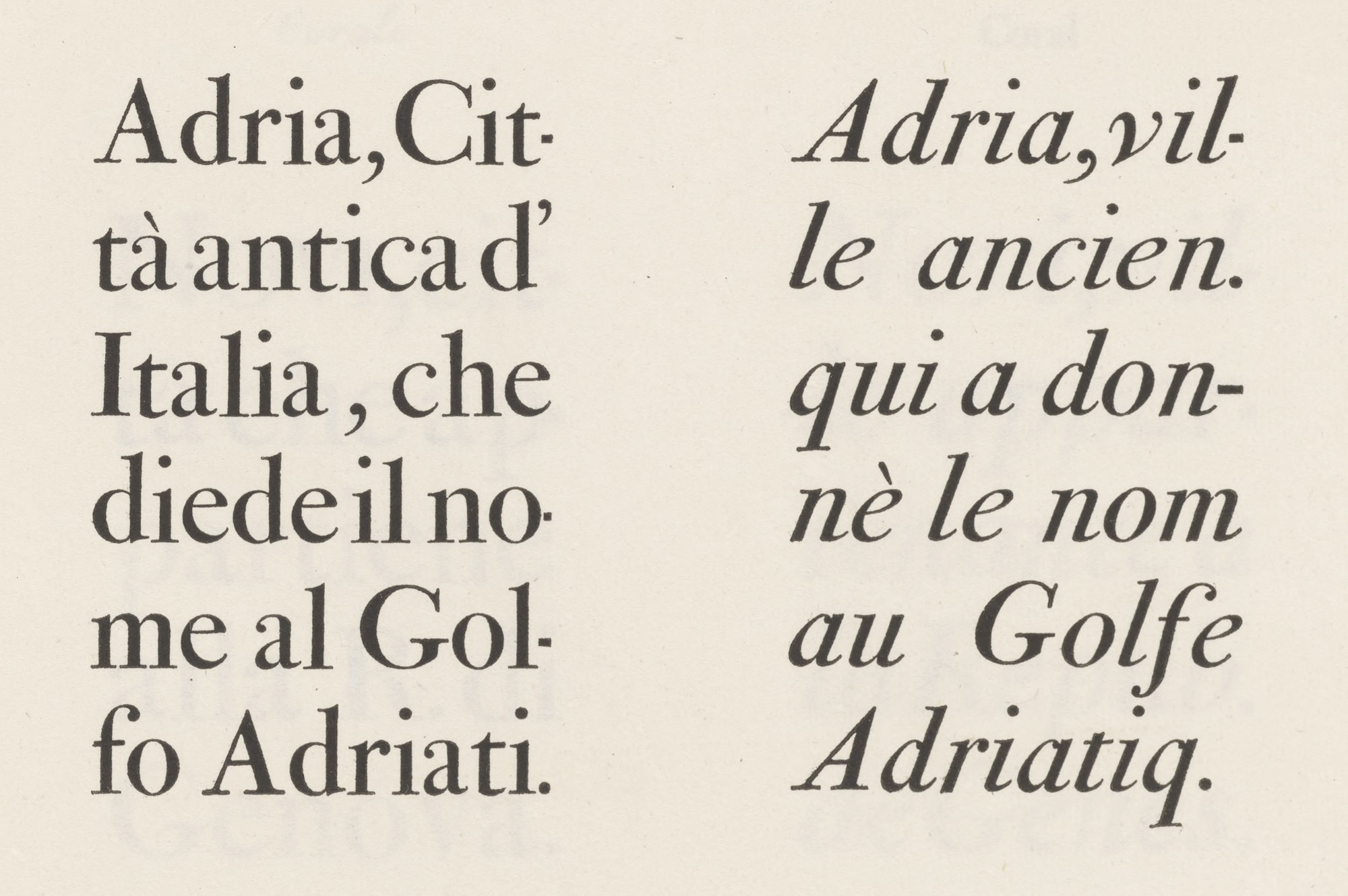

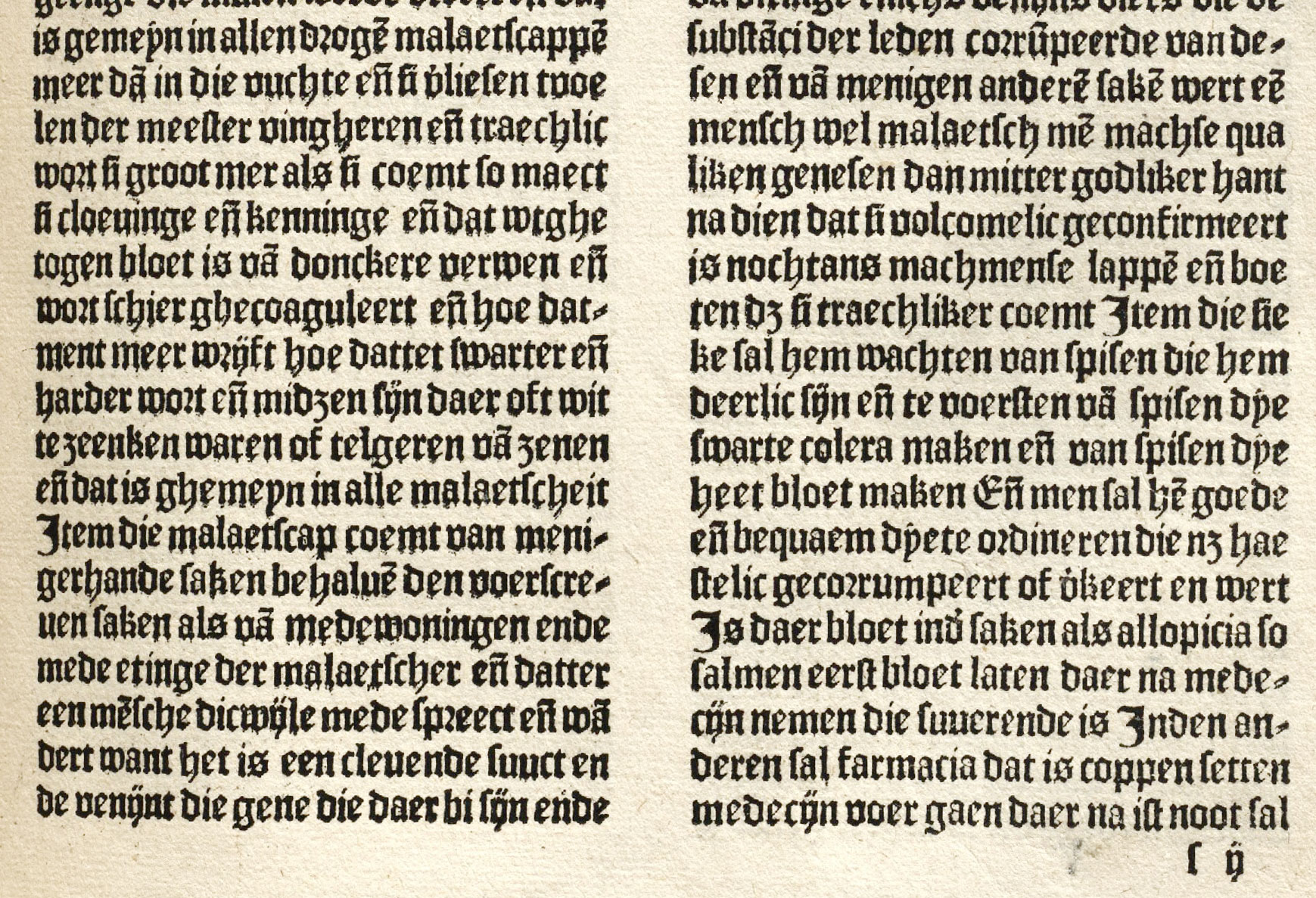

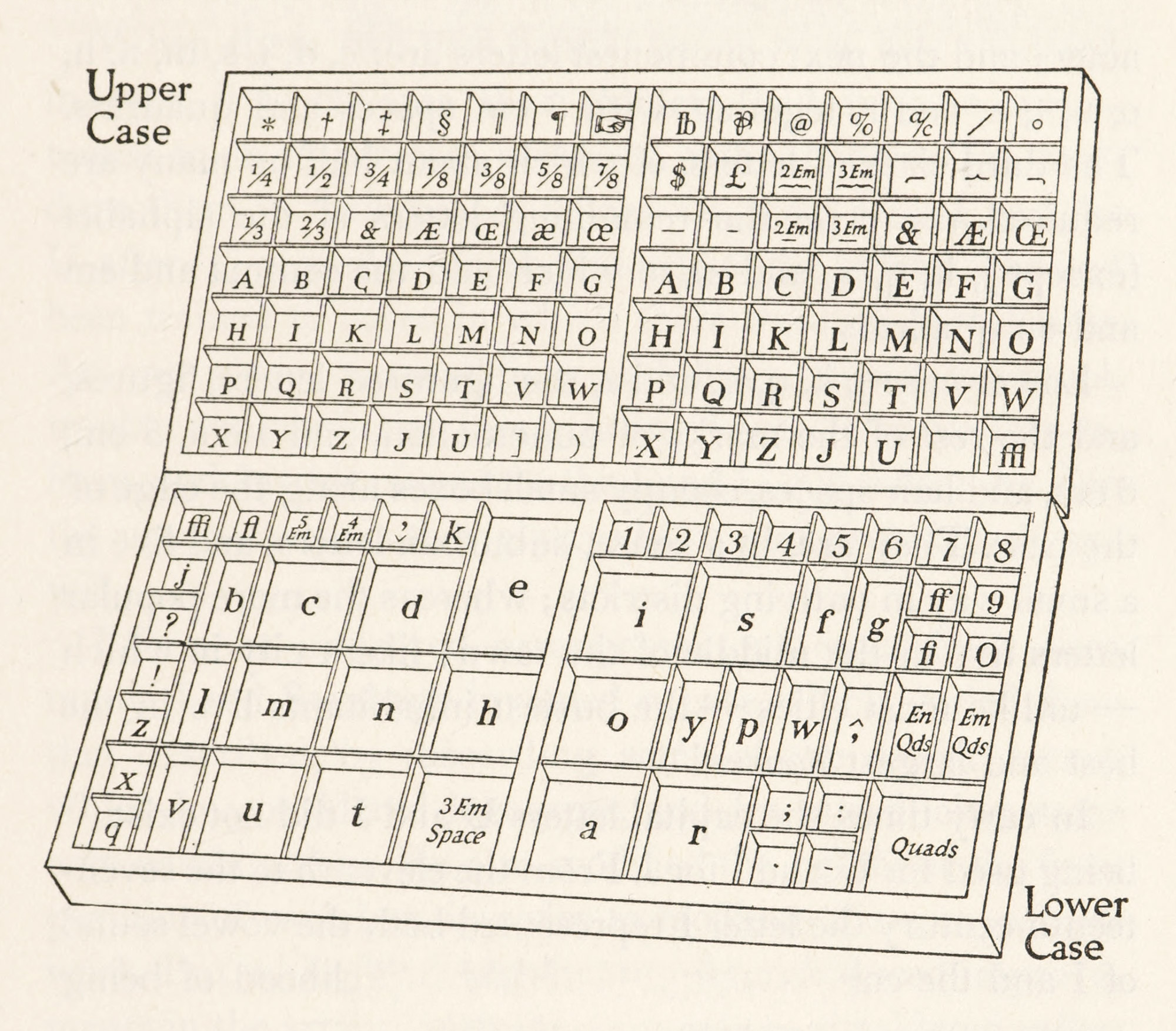

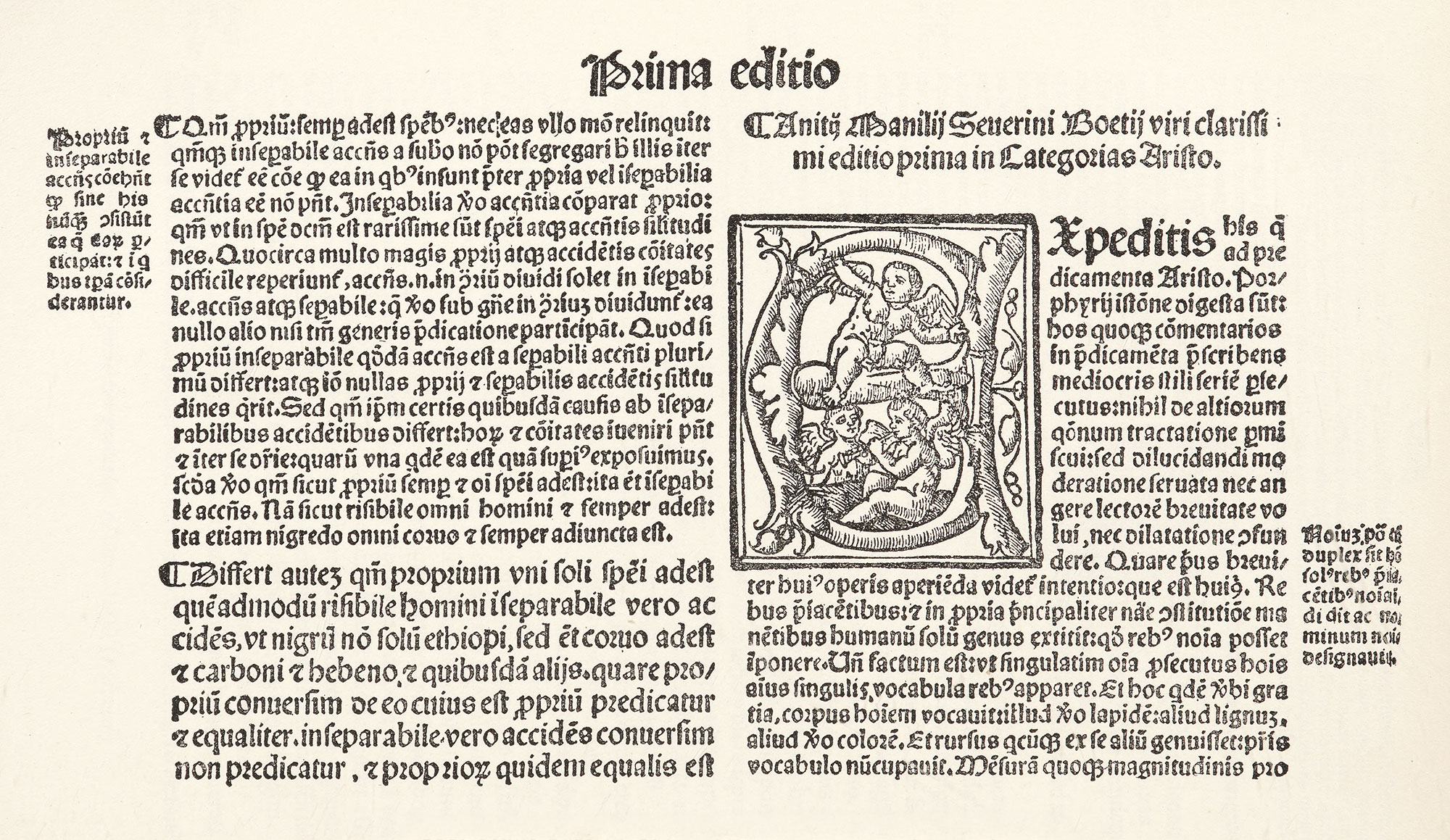

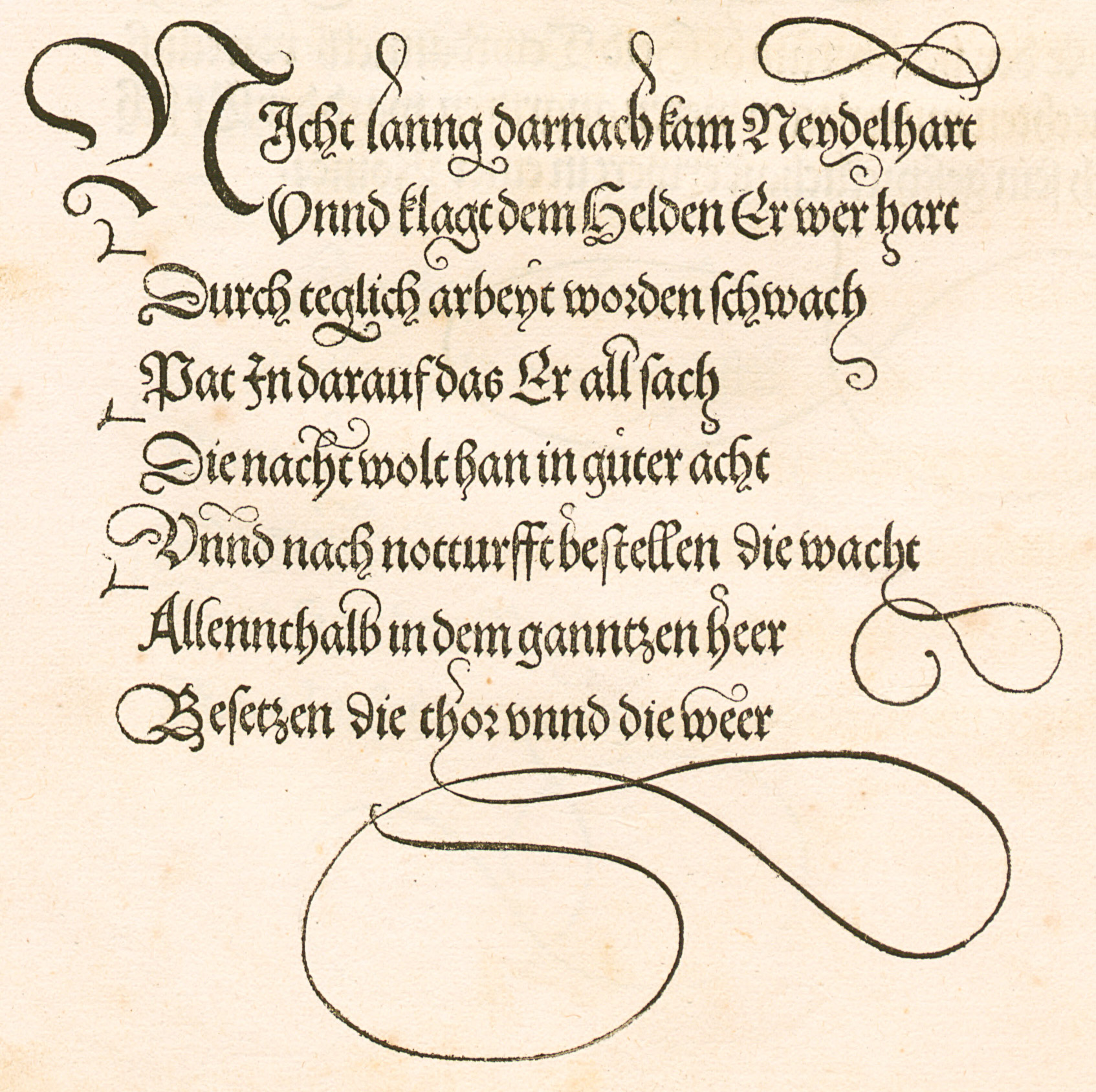

| 8:00 am | Explore a New Digital Edition of Printing Types, the Authoritative History of Printing & Typography from 1922

Times New Roman has been around since 1931, longer than most of us have been alive — and for longer than many of us have been alive, word-processing applications have come with it as the default font. We tend, therefore, to regard it less as something created than as something for all intents and purposes eternal, but there was a time when publishers had to actively adopt it. The first American firm to start using Times New Roman was the Merrymount Press, which had already made a highly prestigious name for itself with publications like the elegant Book of Common Prayer financed by no less a captain of industry than J. Pierpont Morgan. But other printers knew Merrymount for a book that would have inspired in them an equally worshipful impulse.

“Released in 1922 with a later revision in 1937,” Printing Types: Their History, Forms and Use “became known as the standard work on the history of [printing and typography] and a basic book for all interested in the graphic arts. This two-volume work spans nearly 450 years and includes detailed analyses of the printers and type designers and their work.” So writes the designer Nicholas Rougeux, previously featured here on Open Culture for his digital editions of vintage books like Illustrations of the Natural Orders of Plants; British & Exotic Mineralogy; A Monograph of the Trochilidæ, or Family of Humming-Birds; Werner’s Nomenclature of Colours; Euclid’s Elements, and Pierre-Joseph Redouté’s collections of rose and lily illustrations. His latest project to go live is a painstakingly assembled digital edition of Printing Types, which you can explore here.

That book was also originally the work of one man, Merrymount Press founder Daniel Berkeley Updike. “During his tenure at Harvard University, he taught a course on Technique of Printing in the Graduate School of Business Administration for five years,” Rougeux writes, “the lectures of which served as the basis for Printing Types.” In the book, Updike offers a history of “the art of typography from the dawn of Western printing in the fifteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth — focusing primarily on European printing in Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and England as well as the United States.” In tracing “the development of type design,” he also discusses “the importance of each historic period and the lessons they contain for contemporary designers.”

Originally published in 1922 and extensively revised in 1937, Printing Types long stood as the authoritative history of typography in the Latin alphabet, with its “more than 360 facsimile illustrations showcasing examples of typography, borders, flowers, and pages pulled from the books covered.” Tracking down the sources of those illustrations constituted no small part of the painstaking production of Rougeux’s digital edition, and the 100 of them most highly praised by Updike have also been made available for purchase in poster form. For those who do a lot of work with text, in print or digital forms, it could provide just as much motivation as an actual copy of Printing Types on the shelf to find our way beyond the defaults.

Related Content: The History of Typography Told in Five Animated Minutes Discover the First Illustrated Book Printed in English, William Caxton’s Mirror of the World (1481) Behold a Digitization of “The Most Beautiful of All Printed Books,” The Kelmscott Chaucer Fonts in Use: Enter a Giant Archive of Typography, Featuring 12,618 Typefaces Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Tuesday, September 23rd, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | A Trip Around the World in 1900: See Restored Footage Showing Life in New York, London, India, Japan, China & Beyond From today’s vantage, the first decade of the twentieth century can look like an even more distant period of history than it is. In many corners of urban civilization, the cabarets, tearooms, and other near-paralytically mannered institutions of the Belle Époque were very much going concerns. To those who lived in that era, it must have been easy enough to believe that the ways of nineteenth-century-style aristocracy and empire could perpetuate themselves forever. Yet those were also the years of Georges Méliès Le Voyage dans la Lune, the Wright brothers’ first flight; the proliferation of automobiles and subway trains; Russia’s loss in war to Japan and first revolution; Einstein’s discovery of relativity, the photoelectric effect, and Brownian motion; and Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. The world as it was, in other words, was giving way to the world as it would be. Such is the context of the documentary footage collected — and colorized, and upscaled — in the video at the top of the post. Beginning in a bustling working-class street in Hollinwood, England, this tour of the nineteen-hundreds continues on to places like Spain, India, China, New York, Japan, Brazil, Denmark, Austria, and Germany. One aspect of all this footage liable to catch the twenty-first-century eye is all the myriad forms of transportation on display, some running on solely animal or even human muscle, and others propelled by the kind of engines then at the heart of industrial revolutions the world over. (You can even catch a glimpse of Wuppertal’s suspended Schwebebahn, previously featured here on Open Culture.) All this gives us a clearer sense of why so many contemporary observers expressed feelings of civilizational whiplash, especially if, as was becoming more and more common, they’d emigrated from a less technologically advanced society to a more technologically advanced one. For those living at the edge of progress, the shape of things to come (a phrase later used as a book title by one such observer, the prolific H. G. Wells) was anyone’s guess, and it’s hardly surprising that so many forward-looking philosophies, ideologies, and art movements would arise from such a ferment. Still, it would have taken a prescient mind indeed to foresee the ascendance of communism, Nazism, the American empire, and mass broadcast media just ahead, to say nothing of two world wars. William Gibson had yet to be born, let alone to utter his now-famous quote, but as we can see, the future was already here in the nineteen-tens — and unevenly distributed. Related content: Footage of Cities Around the World in the 1890s: London, Tokyo, New York, Venice, Moscow & More Paris Had a Moving Sidewalk in 1900, and a Thomas Edison Film Captured It in Action Immaculately Restored Film Lets You Revisit Life in New York City in 1911 Berlin Street Scenes Beautifully Caught on Film (1900–1914) Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

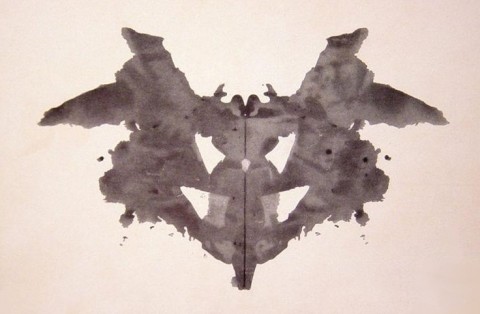

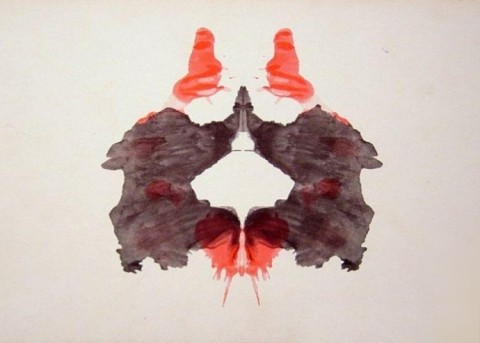

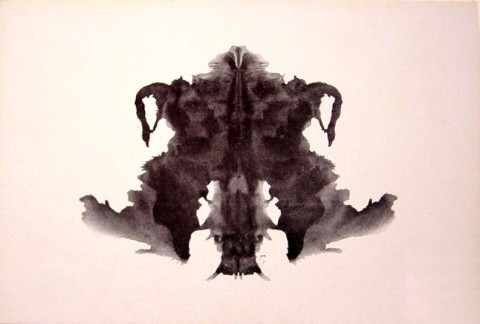

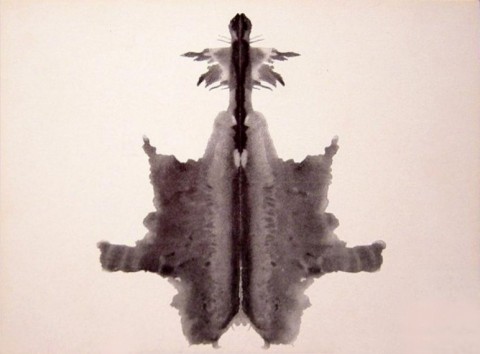

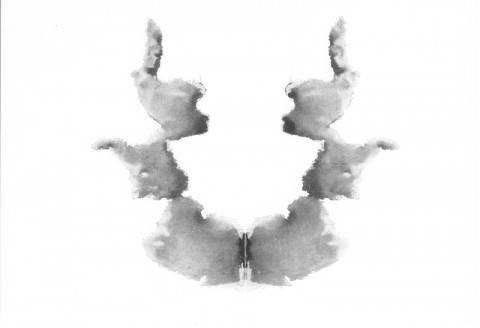

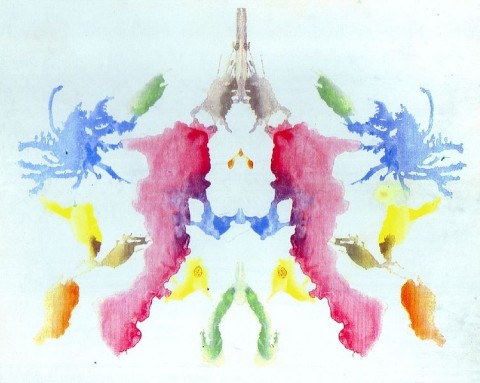

| 8:00 am | Hermann Rorschach’s Original Rorschach Test: What Do You See? (1921) There is a well-known scene in Woody Allen’s Take The Money And Run (1969) when Virgil Starkwell (Allen) takes a psychological test to join the Navy, but is thwarted by his lascivious unconscious. The psychological measure that proves to be Starkwell’s undoing—rejected, he turns to a life of crime—is the Rorschach inkblot test, devised a century ago by Carl Jung’s compatriot and fellow psychologist, Hermann Rorschach. Although Rorschach would die young, at 37, his namesake remains embedded in our perception of psychology, alongside Freud’s couch and Pavlov’s dog. Hermann Rorschach’s father was an art teacher, and encouraged his son to express himself. Whether the young Rorschach had innate artistic leanings, or had begun to listen to his father more closely after the death of his mother at age 12, is uncertain. What is known, however, is that Hermann became so fascinated with making pictures out of inkblots—a Swiss game known under the delightful designation of Klecksography—that his schoolmates gave him the nickname of Klecks. Although he struggled to choose between art and science as a career, Rorschach, on the counsel of eminent German biologist and ardent Darwin supporter Ernst Haeckel, chose medicine, specializing in psychology. Still, he never abandoned art. Even before the young Rorschach began to study psychology, the medical profession had flirted with imagery association. In 1857, a German doctor named Justinus Kerner published a book of poetry, with each poem inspired by an accompanying inkblot. Alfred Binet, the father of intelligence testing, also tinkered with inkblots at the outset of the 20th century, seeing them as a potential measure of creativity. While the claim that Rorschach was familiar with these particular inkblots rests on conjecture, we know that he was familiar with the work of Szymon Hens, an early psychologist who explored his patients’ fantasies using inkblots, as well as Carl Jung’s practice of having his patients engage in word-association. After noticing that schizophrenic patients associated vastly different things with inkblots than other patients, Rorschach, following some experimentation, created the first version of the inkblot test as a measure of schizophrenia in 1921. The test, however, only came to be used as a form of personality assessment when Samuel Beck and Bruno Klopfer expanded its original scope in the late 1930s. Since then, psychologists have frequently used the various aspects of people’s responses (e.g., inkblot focus area) to make judgment calls about broad personality traits. Ironically, Rorschach himself had been skeptical about the inkblots’ value in assessing personality. In honor of Rorschach’s birthday (he was born on this day in 1884), we’ve highlighted his original images below, as well as some of the most popular responses. If you see something else in these images, feel free to let us know in the comments section below. The images, we should note, are in the public domain, and otherwise readily viewable on Wikipedia. And, according to Wikimedia Commons, the images are in the public domain. Image 1: Bat, butterfly, moth Image 2: Two humans Image 3: Two humans Image 4: Animal hide, skin, rug Image 5: Bat, butterfly, moth Image 6: Animal hide, skin, rug Image 7: Human heads or faces Image 8: Animal; not cat or dog Image 9: Human Image 10: Crab, lobster, spider, Happen to see an elephant and a men’s glee club engaged in unmentionable acts? Don’t fret—you’ve likely projected nothing intelligible. The test has long been out of date, and is deemed neither reliable nor valid in the vast majority of cases (although an updated version exists, it suffers from similar methodological flaws). Virgil Starkwell, it seems, would have made a fine Navy officer. Ilia Blinderman is a Montreal-based culture writer. Follow him at@iliablinderman |

| Monday, September 22nd, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | When CBS Canceled The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour for Criticizing the American Establishment and the Vietnam War (1969) Rigorously clean-cut, competent on the acoustic guitar and double bass, and seldom dressed in anything more daring than cherry-red blazers, Tom and Dick Smothers looked like the antithesis of nineteen-sixties rebellion. When they first gained national recognition with their variety show The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, they must have come off to many young viewers as the kind of act of which their mother — or even grandmother — would approve. But the brothers’ cultivatedly square, neo-vaudevillian appearance was deceiving, as CBS would soon find out when the two took every chance to turn their program into a satirical, relentlessly authority-challenging, yet somehow wholesome showcase of the counterculture. The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour premiered in February of 1967, and its first season “featured minimal controversial content,” writes Sarah King at U.S. History Scene. Thereafter, “the show became increasingly political. The brothers invited activist celebrities onto their show, including folk singers Pete Seeger and Joan Baez and singer-actor Harry Belafonte. The show also produced its own political material criticizing the Vietnam War and the politicians who supported it,” not least President Lyndon Johnson. Bringing on Seeger was a daring move, given that he’d been blacklisted from network television for the better part of two decades, though CBS’s censors made sure to cut out the most politically sensitive parts of his act. Even more so was the brothers’ own performance, with George Segal, of Phil Ochs’s “Draft Dodger Rag,” which they ended by urging their audience to “make love, not war.” All this can look fairly tame by today’s standards, but it locked the show — which had become top-rated, holding its own in a time slot against the cultural phenomenon that was Bonanza — into a grudge match with its own network. Before the third season, CBS’ higher-ups demanded that each show be turned in ten days in advance, ostensibly in order to undergo review for sensitive material. In one instance, they claimed that the deadline hadn’t been met and aired a re-run instead, though it may not have been entirely irrelevant that the intended program contained a tribute by Baez to her then-husband, who was being sent to prison for refusing to serve in the military. CBS did broadcast Baez’s performance on a later date, after clipping out the reference to the specific nature of her husband’s offense. A similar struggle took place around the “sermonettes” delivered by David Steinberg, one of which you can see in the video above. The irreverence toward U.S. foreign policy, religion, and much else besides in these and other segments eventually proved too much for the network, which fired the brothers after it had already given the green light to a fourth season of the Comedy Hour. Though they successfully sued CBS for breach of contract thereafter, they never did regain the same level of televisual prominence they’d once enjoyed, if enjoy be the word. At any rate, the fallout of all this controversy firmly installed the Smothers Brothers in the pantheon of twentieth-century free-speech warriors, and their experience reminds us still today that, without the freedom to give offense, there can be no comedy worthy of the name. Related content: Watch Steve Martin Make His First TV Appearance: The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour (1968) When The Who (Literally) Blew Up The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967 Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | Explore the Fascinating Map of Fungi: An Introduction to the Vast Mushroom Kingdom Here on Open Culture, we’ve previously featured Domain of Science’s elaborate infographic maps of such vast fields of intellectual endeavor as mathematics, physics, computer science, quantum physics, quantum computing, chemistry, biology, and medicine. Over time, the series’ creator Dominic Walliman has branched out, as it were, even to kingdoms of the natural world, like plants. With Plantae down, which of the other five has he taken on next? That question is answered in the video above, which introduces Domain of Science’s new Fascinating Map of Fungi. Yes, this big map depicts the realm of the humble mushroom, which “shares the forest with the plants and the animals, but it’s not a plant, and it’s not an animal.” And the mushroom itself, like we’re used to seeing sprouting beneath our feet, is only a small part of the organism: the rest “lives hidden, out of sight, below ground. Beneath every mushroom is a fungal network of hair-like strands called the mycelium,” which begins as a spore. The hugely diverse “fruiting bodies” that they push out of the surface have only one job: “to disperse the spores and grow the next generation.” But only ten percent of fungi species actually do this; the rest don’t produce anything we would recognize as mushrooms at all. About 150,000 species of fungi have been discovered so far. Though inanimate, they manage to do quite a lot, such as supplying nutrients to plants (or killing them), generating chemicals that have proven extremely useful (or at least consciousness-expanding) to humans, hijacking the nervous systems of arthropods, and even surviving in outer space. And of course, “because of their ability to concentrate nutrients from within the soil, fungi are an excellent source of food for us and many other animals.” Mycologists estimate that there remain at least two or three million more species “out there in nature waiting to be discovered.” At least a few of them, one hopes, will turn out to be tasty. Related content: A Stunning, Hand-Illustrated Book of Mushrooms Drawn by an Overlooked 19th Century Female Scientist The Beautifully Illustrated Atlas of Mushrooms: Edible, Suspect and Poisonous (1827) Death-Cap Mushrooms are Terrifying and Unstoppable: A Wild Animation Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Friday, September 19th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

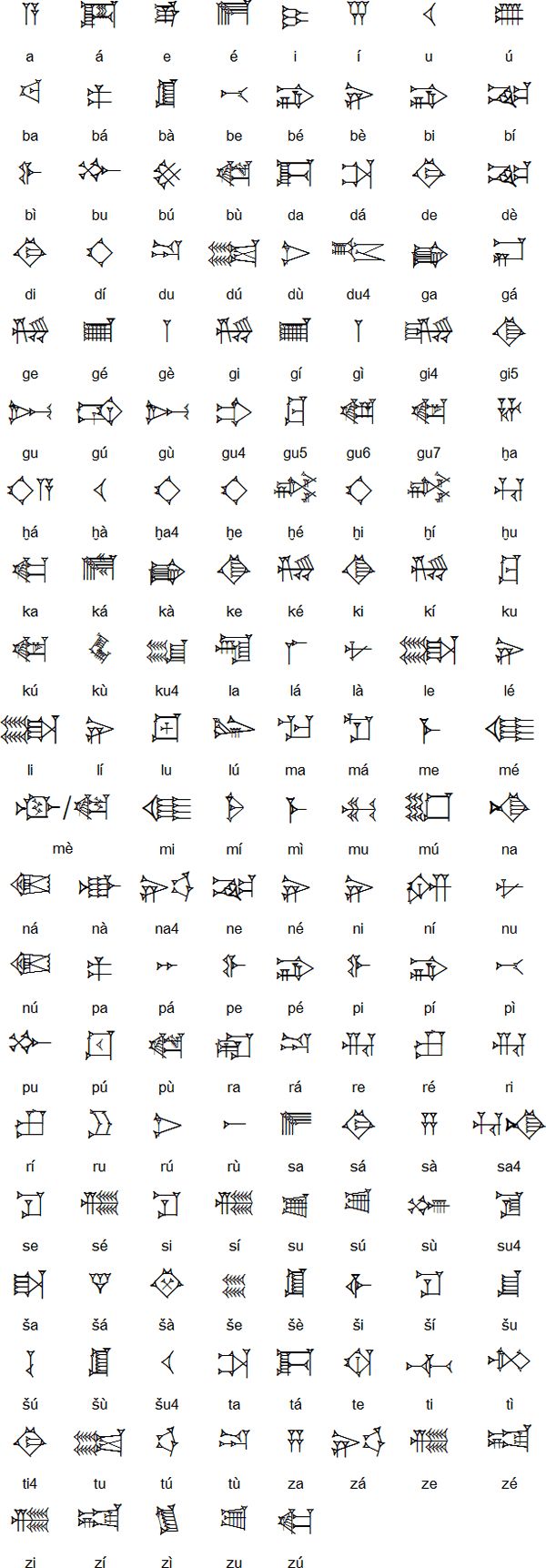

| 9:00 am | How to Write in Cuneiform, the Oldest Writing System in the World: A Short Introduction Teaching child visitors how to write their names using an unfamiliar or antique alphabet is a favorite activity of museum educators, but Dr. Irving Finkel, a cuneiform expert who specializes in ancient Mesopotamian medicine and magic, has grander designs. His employer, the British Museum, has over 130,000 tablets spanning Mesopotamia’s Early Dynastic period to the Neo-Babylonian Empire “just waiting for young scholars to come devote themselves to (the) monkish work” of deciphering them. Writing one’s name might well prove to be a gateway, and Dr. Finkel has a vested interest in lining up some new recruits. The museum’s Department of the Middle East has an open access policy, with a study room where researchers can get up close and personal with a vast collection of cuneiform tablets from Mesopotamia and surrounding regions. But let’s not put the ox before the cart. As the extremely personable Dr. Finkel shows Matt Gray and Tom Scott of Matt and Tom’s Park Bench, above, cuneiform consists of three components—upright, horizontal and diagonal—made by pressing the edge of a reed stylus, or popsicle stick if you prefer, into a clay tablet. The mechanical process seems fairly easy to get the hang of, but mastering the oldest writing system in the world will take you around six years of dedicated study. Like Japan’s kanji alphabet, the oldest writing system in the world is syllabic. Properly written out, these syllables join up into a flowing calligraphy that your average, educated Babylonian would be able to read at a glance.

Even if you have no plans to rustle up a popsicle stick and some Play-Doh, it’s worth sticking with the video to the end to hear Dr. Finkel tell how a chance encounter with some naturally occurring cuneiform inspired him to write a horror novel, which is now available for purchase, following a successful Kickstarter campaign. Begin your cuneiform studies with Irving Finkel’s Cuneiform: Ancient Scripts. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2018. Related Content: Hear The Epic of Gilgamesh Read in its Original Ancient Language, Akkadian Learn Ancient Greek in 64 Free Lessons: A Free Online Course from Brandeis & Harvard Hear the “Seikilos Epitaph,” the Oldest Complete Song in the World: An Inspiring Tune from 100 BC Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist in NYC. |

| Thursday, September 18th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | A 107-Year-Old Irish Farmer Reflects on the Changes He’s Seen During His Life (1965) Talk to a clear-headed 107-year-old today, and you could expect to hear stories of adolescence in the Great Depression, or — if you’re lucky — the Jazz Age seen through a child’s eyes. It’s no common experience to have been formed by the age of radio and live deep into the age of the smartphone, but arguably, Michael Fitzpatrick lived through even greater civilizational transformation. Born in Ireland in 1858, he sat for the interview above 107 years later in 1965, which was broadcast on television. That device was well on its way to saturating Western society at the time, as the automobile already had, while mankind was taking to the skies in jetliners and even to the stars in rocket ships. The contrast between the world into which Fitzpatrick was born and the one in which he eventually found himself is made starker by his being a son of the land. A lifelong farmer, he can honestly reply, when asked to name the biggest change he’s seen, “Machinery.” Not all of his answers come across quite so clearly, owing to his thick dialect that must surely have gone extinct by now, even in rural Ireland. Luckily, the video comes with subtitles, making it easier to understand what he has to say about the advent of the “mowing machine” and his memories of the Bodyke evictions of the eighteen-eighties, when mêlées broke out over a local landlord’s attempt to oust his destitute tenants. One can come up with vaguely analogous events to the Bodyke evictions in the modern world, but in essence, they belong to the long stretch of history when to be human meant to engage in agriculture, or to oversee it. The Industrial Revolution didn’t happen at the same pace everywhere at once, and indeed, Fitzpatrick lived the first part of his life in an effectively pre-industrial reality, before witnessing the scarcely believable process of mechanization take place all around him. He experienced, in other words, the arrival of the civilization into which we were all born, and to which we know no alternative. As for those of us of a certain age today, we can expect to be asked six or seven decades hence — assuming we can go the distance — what life was like with only dial-up internet. Related content: Real Interviews with People Who Lived in the 1800s Philosopher Bertrand Russell Talks About the Time When His Grandfather Met Napoleon 1400 Engravings from the 19th Century Flow Together in the Short Animation “Still Life” A Rare Smile Captured in a 19th Century Photograph Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | An Art Conservator Restores a Painting of the Doomed Party Girl Isabella de’ Medici: See the Before and After Some people talk to plants. The Carnegie Museum of Art’s chief conservator Ellen Baxter talks to the paintings she’s restoring. “You have to … tell her she’s going to look lovely,” she says, above, spreading varnish over a 16th-century portrait of Isabella de’ Medici prior to starting the laborious process of restoring years of wear and tear by inpainting with tiny brushes, aided with pipettes of varnish and solvent. Isabella had been waiting a long time for such tender attention, concealed beneath a 19th-century overpainting depicting a daintier featured woman reputed to be Eleanor of Toledo, wife of Cosimo I de’ Medici, the second Duke of Florence. Louise Lippincott, the CMA’s former curator of fine arts, ran across the work in the museum’s basement storage. Records named the artist as Bronzino, court painter to Cosimo I, but Lippincott, who thought the painting “awful”, brought it to Ellen Baxter for a second opinion. As Cristina Rouvalis writes in Carnegie Magazine, Baxter is a “rare mix of left- and right-brained talent”, a painter with a bachelor’s degree in art history, minors in chemistry and physics, and a master’s degree in art conservation:

The minute she saw the oil painting purported to be of Eleanor of Toledo… Baxter knew something wasn’t quite right. The face was too blandly pretty, “like a Victorian cookie tin box lid,” she says. Upon examining the back of the painting, she identified—thanks to a trusty Google search—the stamp of Francis Leedham, who worked at the National Portrait Gallery in London in the mid-1800s as a “reliner,” transferring paintings from a wood panel to canvas mount. The painstaking process involves scraping and sanding away the panel from back to front and then gluing the painted surface layer to a new canvas. An x‑ray confirmed her hunch, revealing extra layers of paint in this “lasagna”. Careful stripping of dirty varnish and Victorian paint in the areas of the portrait’s face and hands began to reveal the much stronger features of the woman who posed for the artist. (The Carnegie is banking on Bronzino’s student, Alessandro Allori, or someone in his circle.)

Lippincott was also busily sleuthing, finding a Medici-commissioned copy of the painting in Vienna that matched the dress and hair exactly. Thusly did she learn that the subject was Eleanor of Toledo’s daughter, Isabella de’ Medici, the apple of her father’s eye and a notorious, ultimately ill-fated party girl. The History Blog paints an irresistible portrait of this maverick princess: Cosimo gave her an exceptional amount of freedom for a noblewoman of her time. She ran her own household, and after Eleanor’s death in 1562, Isabella ran her father’s too. She threw famously raucous parties and spent lavishly. Her father always covered her debts and protected her from scrutiny even as rumors of her lovers and excesses that would have doomed other society women spread far and wide. Her favorite lover was said to be Troilo Orsini, her husband Paolo’s cousin. Things went downhill fast for Isabella after her father’s death in 1574. Her brother Francesco was now the Grand Duke, and he had no interest in indulging his sister’s peccadilloes. We don’t know what happened exactly, but in 1576 Isabella died at the Medici Villa of Cerreto Guidi near Empoli. The official story released by Francesco was that his 34-year-old sister dropped dead suddenly while washing her hair. The unofficial story is that she was strangled by her husband out of revenge for her adultery and/or to clear the way for him to marry his own mistress Vittoria Accoramboni. Baxter noted that the urn Isabella holds was not part of the painting to begin with, though neither was it one of Leedham’s revisions. Its resemblance to the urn that Mary Magdalene is often depicted using as she anoints Jesus’ feet led her and Lippincott to speculate that it was added at Isabella’s request, in an attempt to redeem her image. “This is literally the bad girl seeing the light,” Lippincott told Rouvalis. Despite her fondness for the subject of the liberated painting, and her considerable skill as an artist, Baxter resisted the temptation to embellish beyond what she found: I’m not the artist. I’m the conservator. It’s my job to repair damages and losses, to not put myself in the painting. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2023. Related Content How Art Conservators Restore Old Paintings & Revive Their Original Colors The Art of Restoring a 400-Year-Old Painting: A Five-Minute Primer A Restored Vermeer Painting Reveals a Portrait of a Cupid Hidden for Over 350 Years How an Art Conservator Completely Restores a Damaged Painting: A Short, Meditative Documentary Free Course: An Introduction to the Art of the Italian Renaissance – Ayun Halliday is the author of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. |

| Wednesday, September 17th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

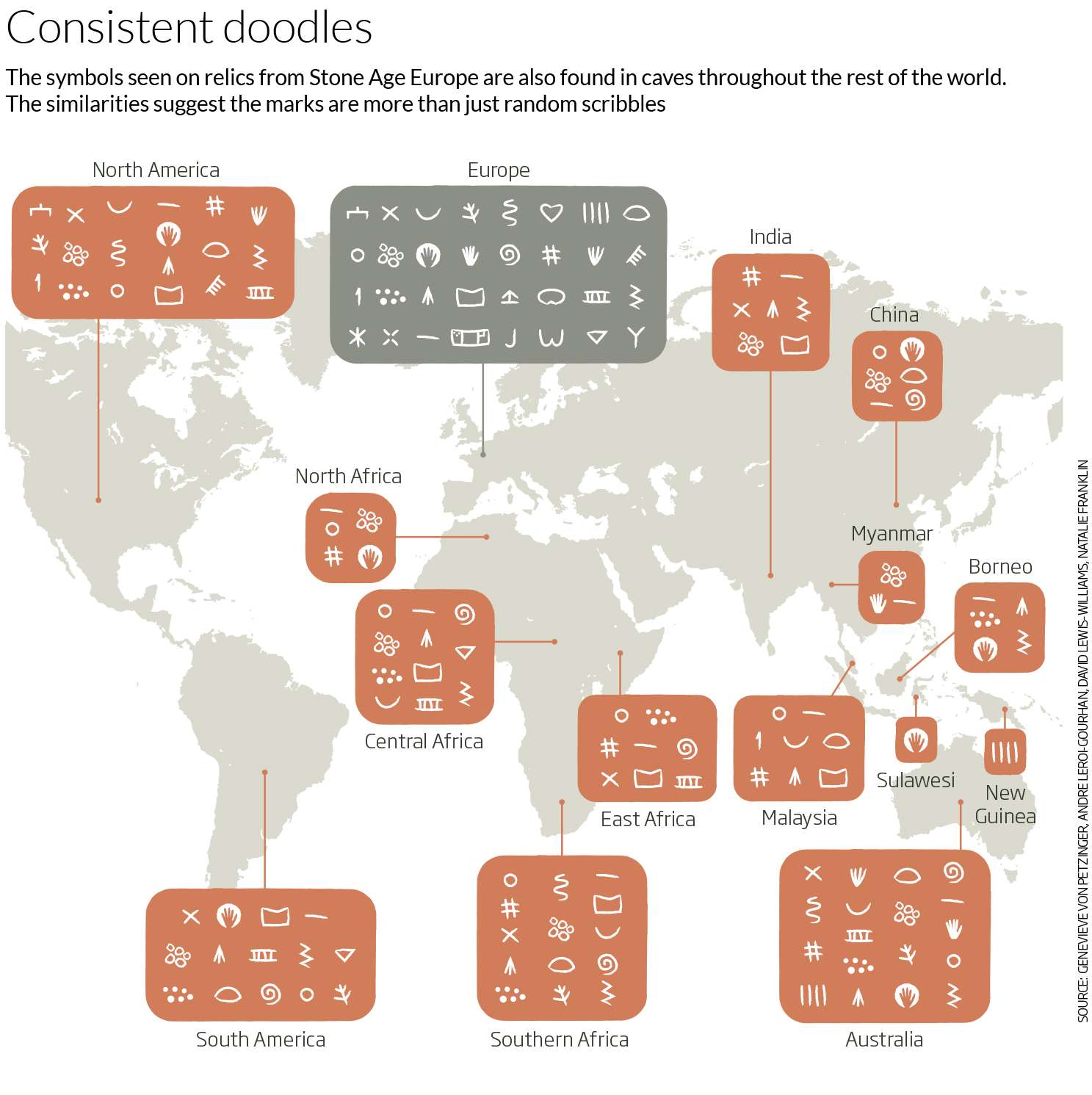

| 9:00 am | 40,000-Year-Old Symbols Found in Caves Worldwide May Be the Earliest Written Language We may take it for granted that the earliest writing systems developed with the Sumerians around 3400 B.C.E. The archaeological evidence so far supports the theory. But it may also be possible that the earliest writing systems predate 5000-year-old cuneiform tablets by several thousand years. And what’s more, it may be possible, suggests paleoanthropologist Genevieve von Petzinger, that those prehistoric forms of writing, which include the earliest known hashtag marks, consisted of symbols nearly as universal as emoji. The study of symbols carved into cave walls all over the world—including penniforms (feather shapes), claviforms (key shapes), and hand stencils—could eventually push us to “abandon the powerful narrative,” writes Frank Jacobs at Big Think, “of history as total darkness until the Sumerians flip the switch.” Though the symbols may never be truly decipherable, their purposes obscured by thousands of years of separation in time, they clearly show humans “undimming the light many millennia earlier.” While burrowing deep underground to make cave paintings of animals, early humans as far back as 40,000 years ago also developed a system of signs that is remarkably consistent across and between continents. Von Petzinger spent years cataloguing these symbols in Europe, visiting “52 caves,” reports New Scientist’s Alison George, “in France, Spain, Italy and Portugal. The symbols she found ranged from dots, lines, triangles, squares and zigzags to more complex forms like ladder shapes, hand stencils, something called a tectiform that looks a bit like a post with a roof, and feather shapes called penniforms.”

She discovered 32 signs found all over the continent, carved and painted over a very long period of time. “For tens of thousands of years,” Jacobs points out, “our ancestors seem to have been curiously consistent with the symbols they used.” Von Petzinger sees this system as a carryover from modern humans’ migration into Europe from Africa. “This does not look like the start-up phase of a brand-new invention,” she writes in her book The First Signs: Unlocking the mysteries of the world’s oldest symbols. In her TED Talk at the top, von Petzinger describes this early system of communication through abstract signs as a precursor to the “global network of information exchange” in the modern world. “We’ve been building on the mental achievements of those who came before us for so long,” she says, “that it’s easy to forget that certain abilities haven’t already existed,” long before the formal written records we recognize. These symbols traveled: they aren’t only found in caves, but also etched into deer teeth strung together in an ancient necklace. Von Petzinger believes, writes George, that “the simple shapes represent a fundamental shift in our ancestors’ mental skills,” toward using abstract symbols to communicate. Not everyone agrees with her. As the Bradshaw Foundation notes, when it comes to the European symbols, eminent prehistorian Jean Clottes argues “the signs in the caves are always (or nearly always) associated with animal figures and thus cannot be said to be the first steps toward symbolism.” Of course, it’s also possible that both the signs and the animals were meant to convey ideas just as a written language does. So argues MIT linguist Cora Lesure and her co-authors in a paper published in Frontiers in Psychology last year. Cave art might show early humans “converting acoustic sounds into drawings,” notes Sarah Gibbens at National Geographic. Lesure says her research “suggests that the cognitive mechanisms necessary for the development of cave and rock art are likely to be analogous to those employed in the expression of the symbolic thinking required for language.” In other words, under her theory, “cave and rock [art] would represent a modality of linguistic expression.” And the symbols surrounding that art might represent an elaboration on the theme. The very first system of writing, shared by early humans all over the world for tens of thousands of years. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2019. Related Content: Tracing English Back to Its Oldest Known Ancestor: An Introduction to Proto-Indo-European Was a 32,000-Year-Old Cave Painting the Earliest Form of Cinema? How to Write in Cuneiform, the Oldest Writing System in the World: A Short, Charming Introduction Dictionary of the Oldest Written Language–It Took 90 Years to Complete, and It’s Now Free Online Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

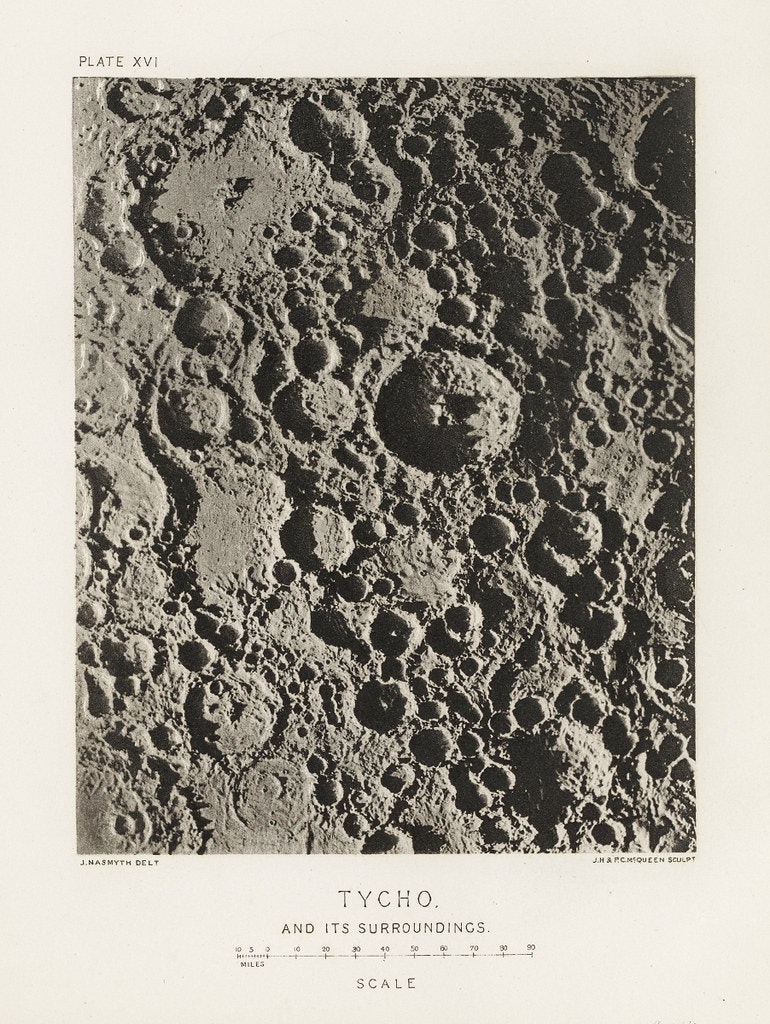

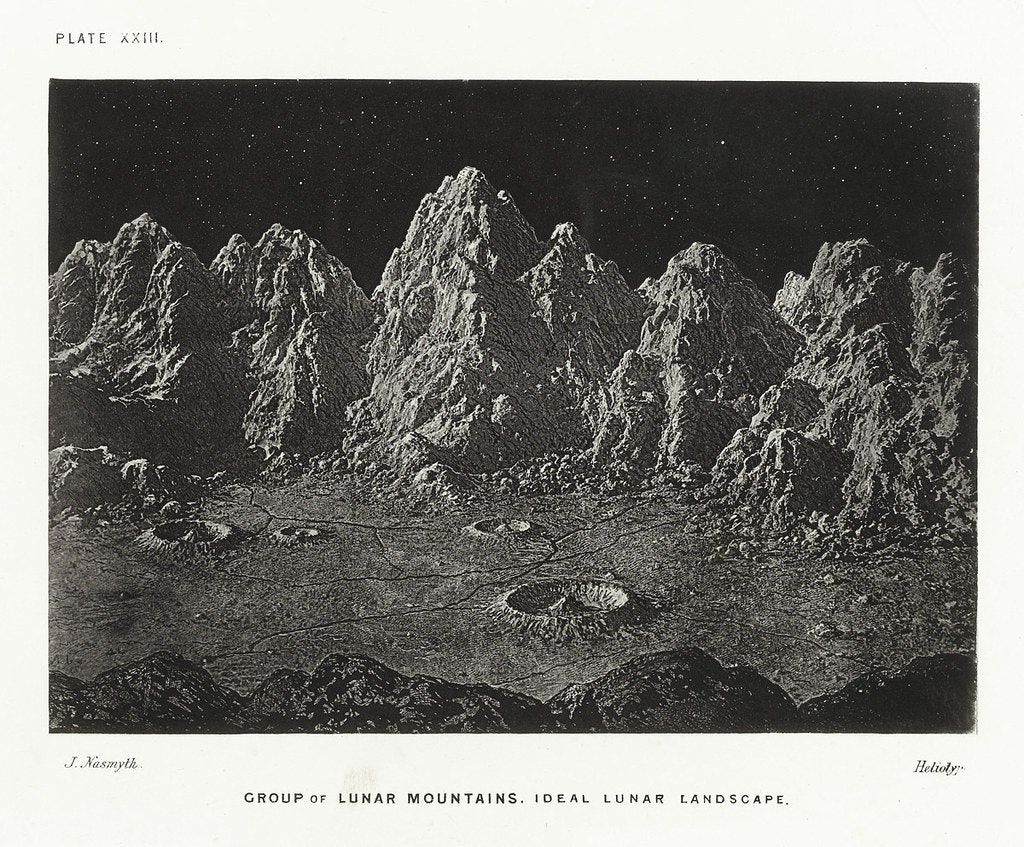

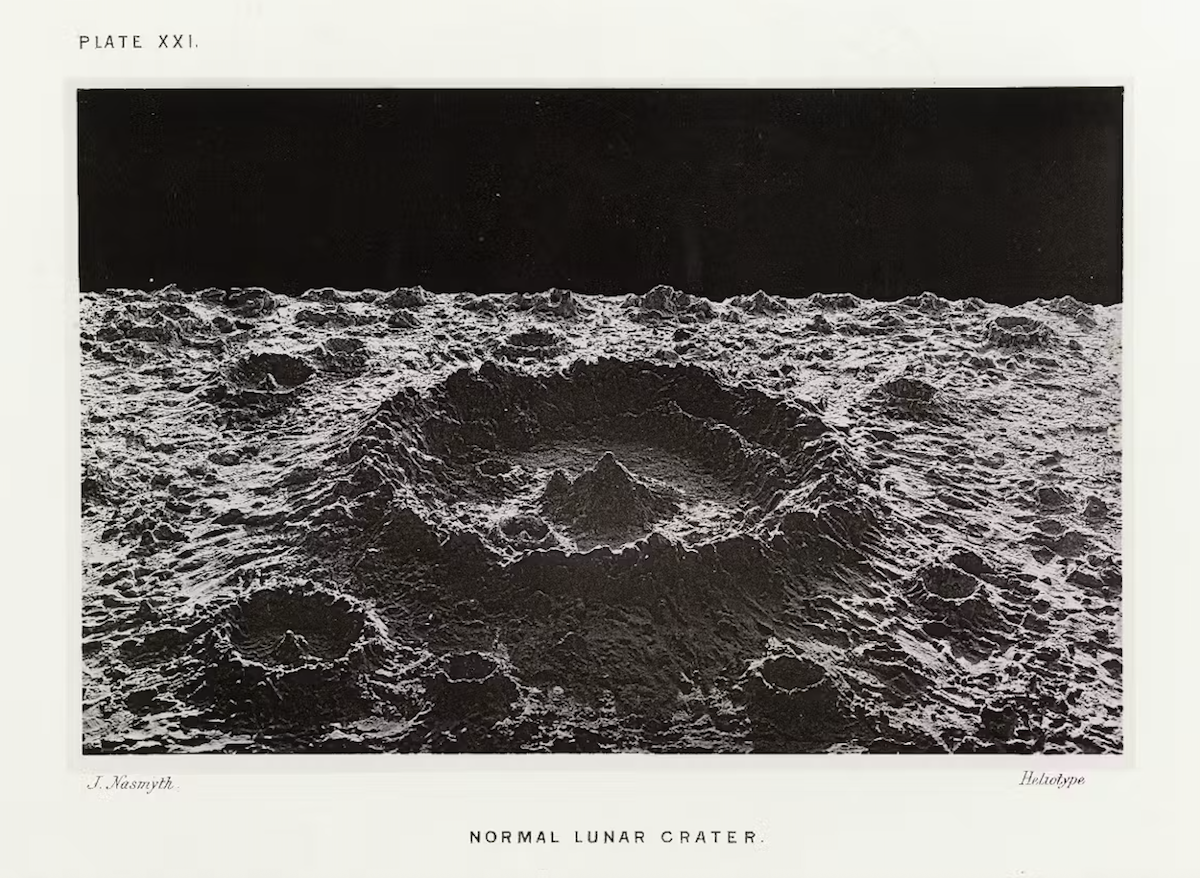

| 8:00 am | How a 19th Century Scientist Created Incredibly Realistic 3D Models of the Moon (1874)

At the moment, there’s no better way to see anything in space than through the lens of the James Webb Space Telescope. Previously featured here on Open Culture, that ten-billion-dollar successor to the Hubble Space Telescope can see unprecedentedly far out into space, which, in effect, means it can see unprecedentedly far back in time: some 13.5 billion years, in fact, to the state of the early universe. We posted the first photos taken by the James Webb Space Telescope in 2022, which showed us distant galaxies and nebulae at a level of detail in which they’d never been seen before.

Such images would scarcely have been imaginable to James Nasmyth, though he might have foreseen that they would one day be a reality. A man of many interests, he seems to have pursued them all during the nineteenth century through which he lived in its near-entirety. His invention of the steam hammer, which turned out to be a great boon to the shipbuilding industry, did its part to make possible his early retirement. At that point, he was freed to pursue such passions as astronomy and photography, and in 1874, he published with co-author James Carpenter a book that occupied the intersection of those fields.

The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite contains what still look like strikingly detailed photos of the surface of that familiar but then-still-mysterious heavenly body: quite a coup at the time, considering that the technology for taking pictures through a telescope had yet to be invented. Nasmyth did use a telescope — one he made himself — but only as a reference in order to sketch “the moon’s scarred, cratered and mountainous surface,” writes Ned Pennant-Rea at the Public Domain Review. “He then built plaster models based on the drawings, and photographed these against black backgrounds in the full glare of the sun.”

In the book’s text, Nasmyth and Carpenter showed a certain scientific prescience with their observations on such phenomena as the “stupendous reservoir of power that the tidal waters constitute.” You can read the first edition at the Internet Archive, and you can see more of its photographs at the Public Domain Review. Compare them to pictures of the actual moon, and you’ll notice that he got a good deal right about the look of its surface, especially given the tools he had to work with at the time. There’s even a sense in which Nasmyth’s photos look more real than the 100 percent faithful images we have now, that they vividly represent something of the moon’s essence. As millions of disappointed viewers of CGI-saturated modern sci-fi movies understand, sometimes only models feel right. Related content: The First Surviving Photograph of the Moon (1840) The Very First Picture of the Far Side of the Moon, Taken 60 Years Ago The Full Rotation of the Moon: A Beautiful, High Resolution Time Lapse Film The Evolution of the Moon: 4.5 Billions Years in 2.6 Minutes A Trip to the Moon (1902): The First Great Sci-Fi Film Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Tuesday, September 16th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

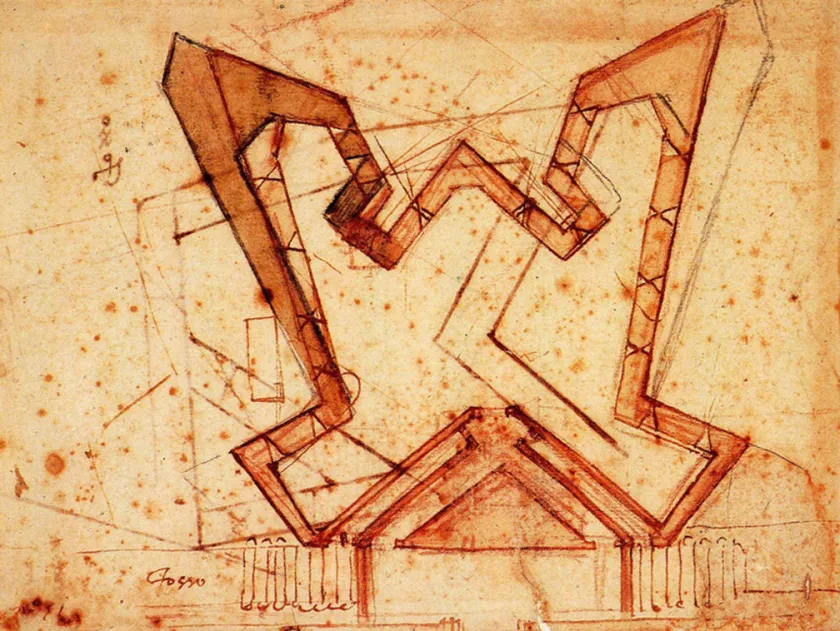

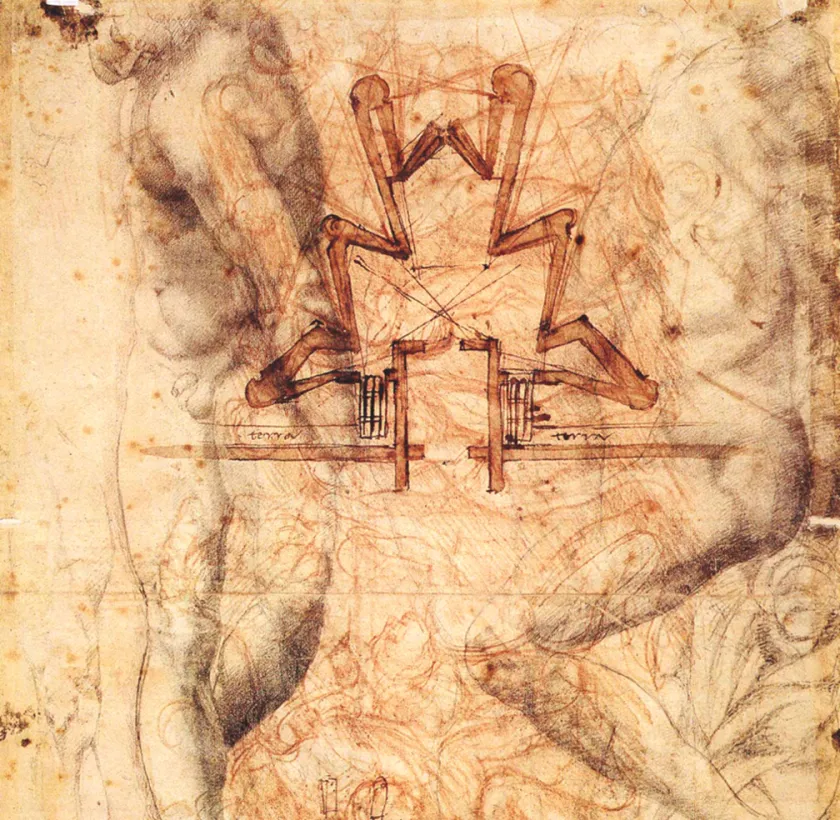

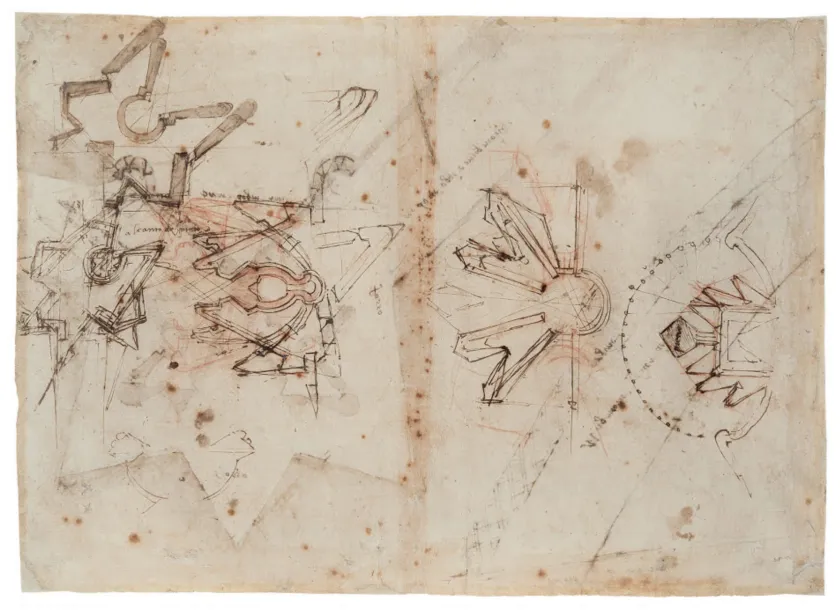

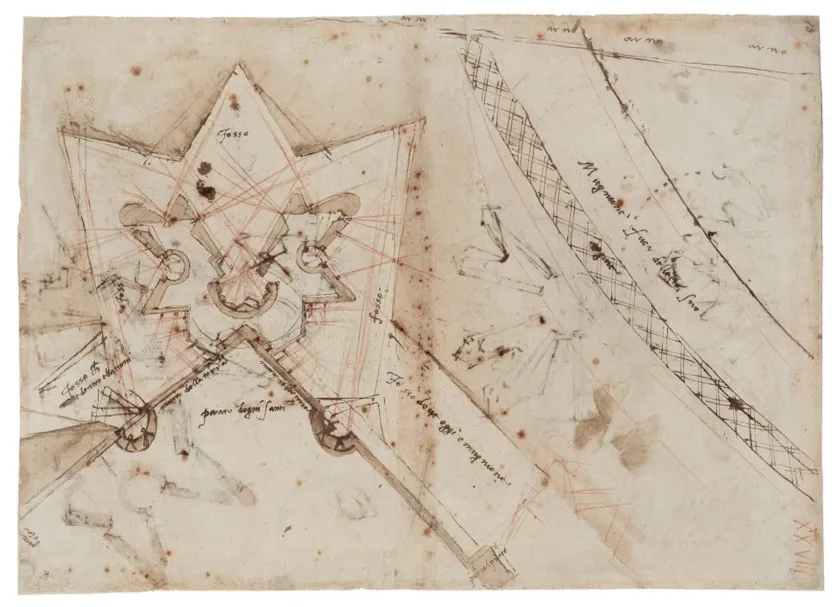

| 9:00 am | When Michelangelo Created Artistic Designs for Military Fortifications to Protect Florence (1529–1530)

Michelangelo was born in the Republic of Florence, with the talent of… well, Michelangelo. Given those beginnings, it would have been practically impossible for him to avoid entanglement with the House of Medici, the banking family and political dynasty that ruled over Florence for the better part of three centuries. By the time of Michelangelo’s birth, in 1475, the Medici had been in power for four decades. At the age of fourteen, he was taken in by Lorenzo de’ Medici, known as “il Magnifico,” in whose household he received artistic training as well as philosophical knowledge and political connections.

It was with Lorenzo’s death in 1492 that this first streak of Medici dominance ran into choppy waters. When the family was expelled from Florence two years later, Michelangelo took his leave as well, beginning the period of his career in which he would sculpt both the Pietà and the David. Only in 1512 (after various troubles in Florence that included the four-year theocracy of Savonarola) were the Medici restored to power, but they also had the papacy: the Medici popes Leo X and Clement VII commissioned a great deal of work from Michelangelo, though he seldom saw eye-to-eye with those particular patrons.

When Florence rebelled against the Medici in the late fifteen-twenties, Michelangelo took the side of the republicans. Their government selected him as one of the “Nine of the Militias” meant to design fortifications for the threatened city (a resumption of earlier, abandoned Medici plans) in 1526, and before long appointed him governatore generale. It was in that capacity that he drew the sketches seen here, which constitute his plans for a set of fortifications against the Medici-backed siege that spanned 1529 and 1530. However artistically striking, their designs were never actually built, at least not in anything like their entirety.

As it happened, Michelangelo had backed the wrong horse: the siege was ultimately successful, and the Medici retook power under the aegis of Holy Roman emperor Charles V. This put the artist in a difficult position, and for a period of months he was forced to go into hiding. With his death sentence in effect, he lay low in a small chamber beneath the Basilica of San Lorenzo, now part of the Medici Chapels Museum, whose walls are covered in drawings, previously featured here on Open Culture, in his unmistakable hand. The artistic skills he’d kept sharp during that period of internal exile would probably have kept serving him well enough in Florence after Clement VII guaranteed his safety there. But it seems he’d had enough Florentine intrigue for one lifetime, the rest of which he wisely opted to spend in Rome. Related content: A Secret Room with Drawings Attributed to Michelangelo Opens to Visitors in Florence How Michelangelo’s David Still Draws Admiration and Controversy Today New Video Shows What May Be Michelangelo’s Lost & Now Found Bronze Sculptures Watch the Painstaking and Nerve-Racking Process of Restoring a Drawing by Michelangelo Michelangelo’s Illustrated Grocery List Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Monday, September 15th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | Everything That Went Wrong During The Wizard of Oz’s Seriously Troubled Production The Wizard of Oz is now showing at Las Vegas’ Sphere. Or a version of it is, at any rate, and not one that meets with the approval of all the picture’s countless fans. “The beloved 1939 film starring Judy Garland, widely considered one of the greatest Hollywood classics, has been stretched and morphed and adapted to fit the enormous dome-shaped venue,” writes the New York Times’ Alissa Wilkinson. This entailed an extension “upward and outward with the help of A.I. as well as visual effects artists. The cool tornado created by Arnold Gillespie for the original has been traded for something digital, and eventually you can’t see it at all, because you’re inside the funnel. New performances and vistas have also been generated,” which is “at best questionable” ethically, to say nothing of the aesthetics. Yet even given the considerable modifications to — and excisions from — the original film, “most audiences will gladly overlook all of this, wowed by the sheer scale of the spectacle.” The Wizard of Oz has, as has often been said, the kind of “magic” that endures through even great deficiencies in presentation. That quality first became apparent in 1956, seventeen years after the movie’s release in cinemas, when it first aired on television. Though the dramatic transition from black-and-white to color would have been lost on most home viewers at the time, “45 million people tuned in, far more than those who had seen it in theaters,” says the narrator of the It Was A Sh*t Show video above. Another broadcast, in 1959, did even better, and thereafter The Wizard of Oz became an “annual must-see event” on TV, which eventually made it “the most-watched film in history.” That status justifies the movie’s infamously troubled production, which is the video’s central subject. From its numerous rewrites all the way through to its feeble box office performance, The Wizard of Oz encountered severe difficulties every step of the way, which gave rise to rumors that continue to haunt it: that an actor died from poison makeup, for example, or that one of the munchkins committed suicide in view of the camera. While the production caused no fatalities — at least not directly — it did come close more than once, to say nothing of the psychological toll the combination of high ambition and persistent dysfunction must have taken on many, if not most, of its participants. Even hearing enumerated only its clearly documented problems is enough to make one wonder how the picture was ever completed in the first place. Yet now, 86 years later, its Sphere reinterpretation is raking in $2 million in ticket sales per day: an act of wizardry if ever there was one. Related content: Watch the Earliest Surviving Filmed Version of The Wizard of Oz (1910) The Wizard of Oz Broken Apart and Put Back Together in Alphabetical Order The Complete Wizard of Oz Series, Available as Free eBooks and Free Audio Books Hear Waiting for Godot, the Acclaimed 1956 Production Starring The Wizard of Oz’s Bert Lahr Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

| Tuesday, September 16th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

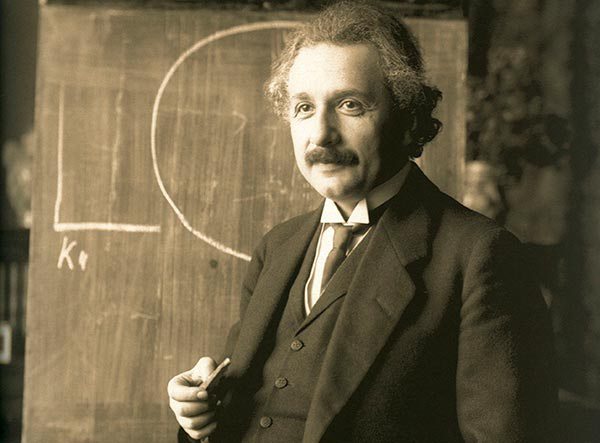

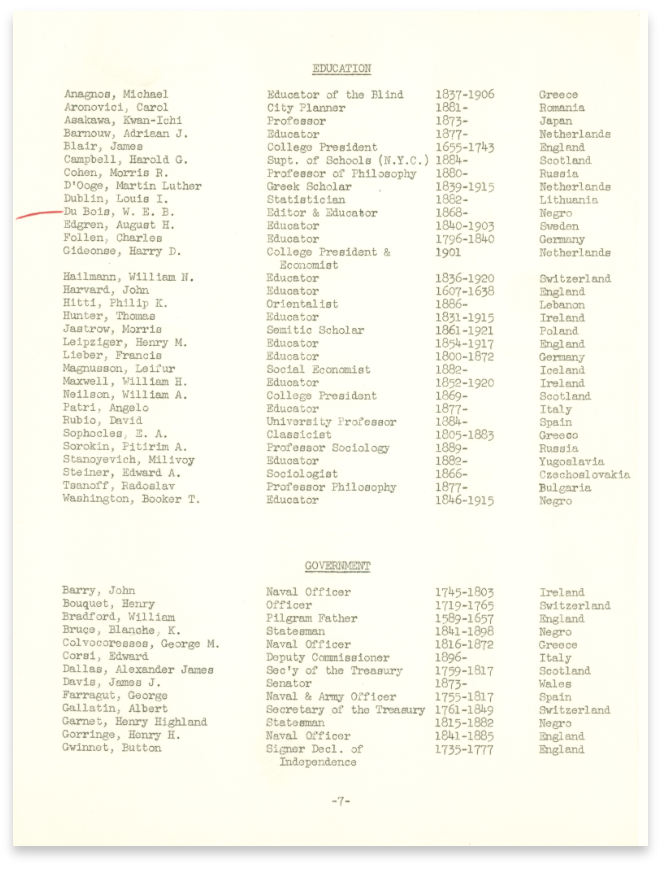

| 8:00 am | Albert Einstein Gives a Speech Praising Immigrants’ Contributions to America (1939)

There have been many times in American history when celebrations of the country’s multi-ethnic, ever-changing demography served as powerful counterweights to narrow, exclusionary, nationalisms. In 1855, for example, the publication of Brooklyn native Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself offered a “passionate embrace of equality,” writes Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, “the soul of democracy.” We can contrast the vibrancy and dynamism of Whitman’s vision with the violent nativism of the anti-immigrant Know-Nothings, who reached their peak in the 1850s. The movement was founded by two other New Yorkers, gang leader William “Bill the Butcher” Poole and writer Thomas R. Whitney, who asked in one of his political tracts, “What is equality but stagnation?” Almost 100 years later, we see another nationalist movement taking hold, not only in Europe, but in the States. Before the U.S. entered World War II, its views on National Socialist Germany were decidedly ambivalent, with glowing portraits of its leader published throughout the 30s, and a sizable Nazi presence in the U.S. From 1934 to 1939, for example, German groups in the U.S. organized massive rallies in Madison Square Garden. Additionally, the German-American Bund promoted the Nazi Party throughout the U.S. with 70 different local chapters. These organizations held Nazi family and summer camps in New Jersey, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania…. “There were forced marches in the middle of the night to bonfires,” says historian Arnie Bernstein, “where the kids would sing the Nazi national anthem and shout ‘Sieg Heil.’”  Needless to say, these scenes made a number of minority groups and immigrants particularly nervous, especially Jews who had just escaped from Europe. One such immigrant, physicist Albert Einstein, had made the U.S. his permanent home in 1933 when he accepted a position at Princeton after living as a refugee in England. He would go on to become a forceful advocate for equality in the U.S., speaking out against the racial caste system of segregation. In 1940, Einstein gave a little-known speech at the New York World’s Fair to inaugurate an exhibit that paid “homage to the diversity of the U.S. population.” On the display, called the “Wall of Fame,” were inscribed “the names and professions of hundreds of the nation’s most notable ‘immigrants, Negroes and American Indians.’” (See the first page of the typed list above, and the full list here.) Einstein’s speech comes to us via Speeches of Note, a sibling of two favorite sites of ours, Letters of Note and Lists of Note. Below, you can read the full transcript of the speech, in which Einstein—having adopted the country as it had adopted him—-declaims, “these, too, belong to us, and we are glad and grateful to acknowledge the debt that the community owes them.”

The speech is remarkable for its egalitarianism. The exhibit works more or less as a “who’s who” of notable personalities—all of them men. Of course, Einstein himself was one of the most notable immigrants of the age. And yet, his ethos is Whitmanian, celebrating the multitudes of laborers and artists “blossoming namelessly” and those who have “remained unknown.” The country, Einstein suggests, could not possibly be itself without its diversity of people and cultures. That same year, Einstein would pass his citizenship test, and explain in a radio broadcast, “Why I am an American.” Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2017. Related Content: Albert Einstein Expresses His Admiration for Mahatma Gandhi, in Letter and Audio Rare Audio: Albert Einstein Explains “Why I Am an American” on Day He Passes Citizenship Test (1940) Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. |

| Monday, September 15th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 8:00 am | Leonardo Da Vinci’s To-Do List from 1490: The Plan of a Renaissance Man

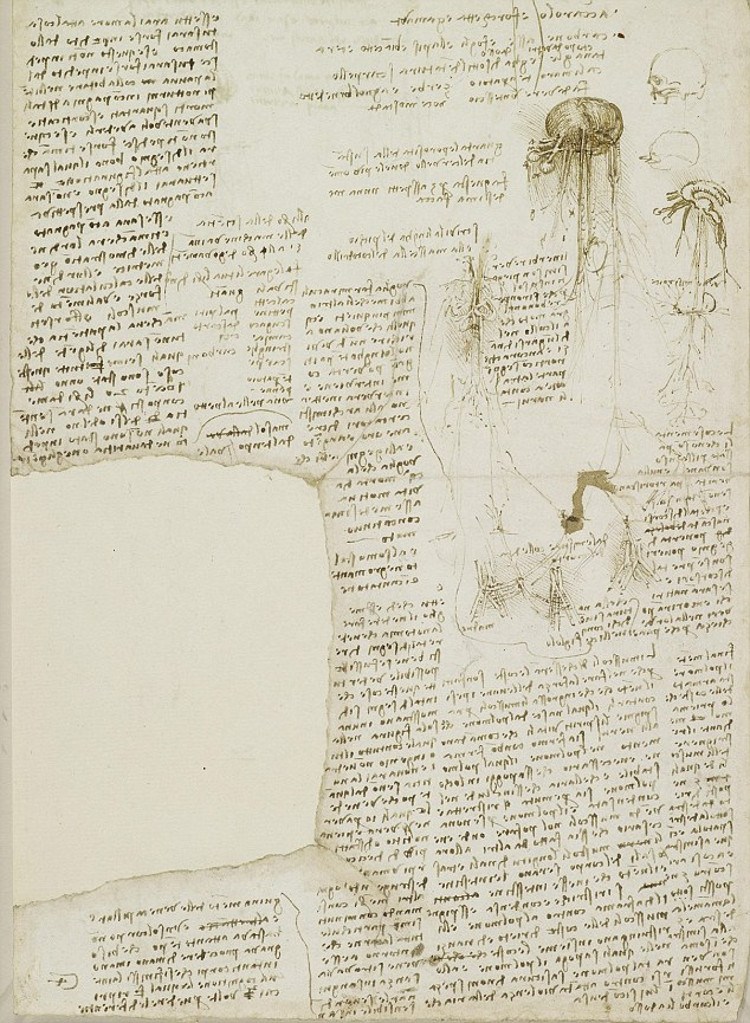

Most people’s to-do lists are, almost by definition, pretty dull, filled with those quotidian little tasks that tend to slip out of our minds. Pick up the laundry. Get that thing for the kid. Buy milk, canned yams and kumquats at the local market. Leonardo Da Vinci was, however, no ordinary person. And his to-do lists were anything but dull. Da Vinci would carry around a notebook, where he would write and draw anything that moved him. “It is useful,” Leonardo once wrote, to “constantly observe, note, and consider.” Buried in one of these books, dating back to around the 1490s, is a to-do list. And what a to-do list. NPR’s Robert Krulwich had it directly translated. And while all of the list might not be immediately clear, remember that Da Vinci never intended for it to be read by web surfers 500 years in the future.

You can just feel Da Vinci’s voracious curiosity and intellectual restlessness. Note how many of the entries are about getting an expert to teach him something, be it mathematics, physics or astronomy. Also who casually lists “draw Milan” as an ambition?

Later to-do lists, dating around 1510, seemed to focus on Da Vinci’s growing fascination with anatomy. In a notebook filled with beautifully rendered drawings of bones and viscera, he rattles off more tasks that need to get done. Things like get a skull, describe the jaw of a crocodile and tongue of a woodpecker, assess a corpse using his finger as a unit of measurement. On that same page, he lists what he considers to be important qualities of an anatomical draughtsman. A firm command of perspective and a knowledge of the inner workings of the body are key. So is having a strong stomach. You can see a page of Da Vinci’s notebook above but be warned. Even if you are conversant in 16th century Italian, Da Vinci wrote everything in mirror script. Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in December, 2014. If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day. If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks! Related Content: Leonardo da Vinci’s Handwritten Resume (Circa 1482) Thomas Edison’s Hugely Ambitious “To-Do” List from 1888 Umberto Eco Explains Why We Make Lists Johnny Cash’s Short and Personal To-Do List Jonathan Crow is a writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. |

| Friday, September 12th, 2025 | |

| LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose. | |

| 9:00 am | The Horrifying Paintings of Francis Bacon Mention Francis Bacon, and you sometimes have to clarify which one you mean: the twentieth-century painter, or the seventeenth-century philosopher? Despite how much time separated their lives, the two men aren’t without their connections. One may actually have been a descendant of the other, if you credit the artist’s father’s claim of relation to the Elizabethan intellectual’s half-brother. Better documented is how the more recent Francis Bacon made a connection to the time of the more distant one, by painting his own versions of Diego Velázquez’s Portrait of Innocent X. We refer, of course, to his “screaming popes,” the subject of the new Hochelaga video above. As Hochelaga creator Tommie Trelawny puts it, “no image captured his imagination more” than Velázquez’s depiction of Pope Innocent X, which is “considered to be one of the finest works in Western art.” Bacon’s version from 1953, after he’d more than established himself in the English art scene, is “a terrible and frightening inversion of the original. The Pope screams as if electrocuted in his golden throne. Violent brushstrokes sweep across the canvas like bars of a cage, stripping away all sense of grandeur and leaving only brutality and pain.” In many ways, this harrowing image came as the natural meeting of existing currents in Bacon’s work, which had already drawn from the history of Christian art and employed a variety of anguished, isolated figures. Unsurprisingly, Bacon’s Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X inspired all manner of controversy. The artist himself denied all interpretations of its supposed implications, insisting that “recreating this papal portrait was simply an aesthetic choice: art for the sake of art.” In any case, he followed it up with about 50 more screaming popes, each of which “embodies a different facet of human darkness.” These and the many other works of art Bacon created prolifically until his death in 1992 reflect what seems to have been his own troubled soul and perpetually disordered life. His style changed over the decades, becoming somewhat softer and less aggressively disturbing, suggesting that his demons may have gone into at least partial retreat. But could anyone capable of painting the screaming popes ever truly have lost touch with the abyss? Related content: The Brilliantly Nightmarish Art & Troubled Life of Painter Francis Bacon Francis Bacon on The South Bank Show: A Singular Profile of the Singular Painter William Burroughs Meets Francis Bacon: See Never-Broadcast Footage (1982) The “Dark Relics” of Christianity: Preserved Skulls, Blood & Other Grim Artifacts The Scream Explained: What’s Really Happening in Edvard Munch’s World-Famous Painting Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall. |

LJ.Rossia.org makes no claim to the content supplied through this journal account. Articles are retrieved via a public feed supplied by the site for this purpose.