|

|

| Пишет larvatus ( @ 2005-01-03 22:34:00 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

sinners and saints

Michael is having dinner with his friend David A. David is a trial lawyer. He is a member of the plaintiffs’ bar. He makes political contributions to the Democrats. David roots for the underdog. He represents Michael against the libel lawsuit by WebEx. WebEx is complaining about Michael’s public account of their failed coverup of child rape by their founder Min Zhu. Min Zhu’s sexual abuse of his daughter Erin is a matter of public record. The outed daughter rapist has since lost his job as WebEx President. He has testified under oath about his plans to “retire” altogether.

Michael credits himself with bringing his degeneracy to the attention of WebEx employees and investors. He thinks of Dante Alighieri encountering in Canto 15 of the Inferno his old master Brunetto Latini.

Brunetto’s sin is sodomy. Dante’s testimony is the only evidence of Brunetto’s sodomite proclivities that we possess. Dante’s outing of sexual perversion is the first such instance that we know. His pen permanently degrades courtly scholar Brunetto to a grotesque apparition.

The lowest among incontinent sinners, sodomites are punished in the seventh circle of Hell for their violent love. It is violence of the worst kind, violence committed against God:

In their midst Dante finds Myrrha, the incestuous daughter, “she who loved her father past the limits of just love”, she who “came to sin with him by falsely taking another’s shape upon herself”, whose tale came to Dante by way of Ovid, from the Tenth Book of his Metamorphoses.

Below her, avoided by Dante amidst the giants in the Ninth Circle, resides the giant Tityus, whose mere attempt to rape Latona, mother of Apollo and Diana, causes his eternal torment by a vulture continuously feeding on his constantly regenerating liver.

The poets of classical antiquity painted vivid images of Tituys’ punishment:

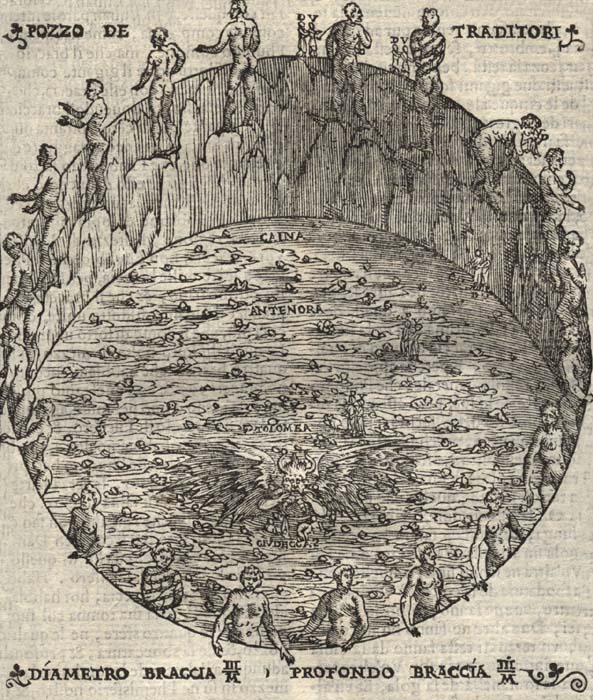

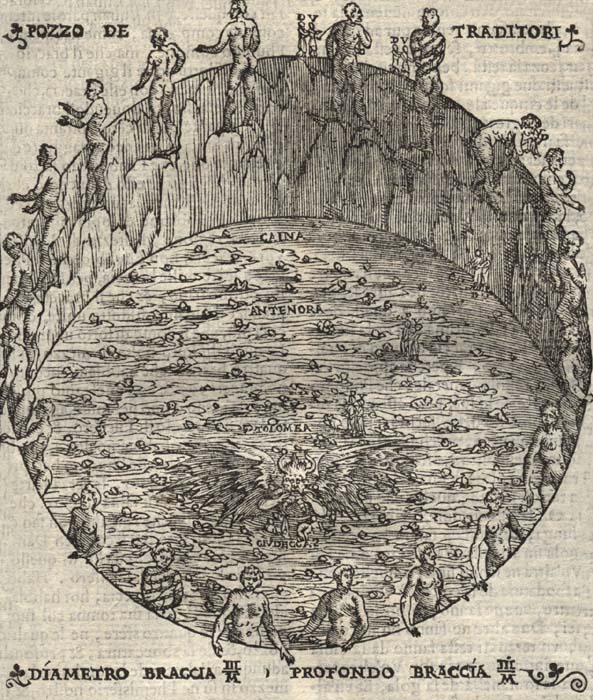

And so, in Cocytus, inside the fourth ring of the ninth circle of Dante’s Inferno, traitors against their benefactors lie immobilized, totally covered in ice:

A child in her parents’ home benefits from the most sacred bond of hospitality. Conjured forth by sex, she enters their household in a state of utter dependence upon her hosts. Michael reflects on the character of a man that violently betrays this bond, exploiting her dependence for the sake of expending his lust. In the character of unnatural fatherhood, distorted by violent lust, the daughter rapist descends from the high tragedy of Myrrha making her fatal unfilial advances to unwitting Cinyras, to the common realm of the rustic folktale, ill suited to a civilized setting. He wonders what possessed him to invest his labor in an enterprise conceived between his former best friend and her child rapist father. He cannot fathom his own choices at the turn of the millennium.

Michael met David in 1999. At that time, Michael was in a business partnership with his ex-girlfriend Erin Zhu. They were looking for corporate counsel to assist them in the deal Erin made with WebEx, an Internet startup co-founded by her father. David came recommended by Michael’s friend Lenny R. Lenny graduated from Caltech with a PhD in applied mathematics. He was running his own technology startup after buying out his former partner. Lenny’s advice was to get a trial lawyer, because sooner or later, all partnerships wound up in litigation. His prophecy fulfilled itself within the year. WebEx breached their contract with Erin and Michael. Instead of complaining on business grounds, Erin hired their friend David on a token contingent fee basis of 2.5%, to sue her father for childhood sexual abuse. She promised to buy out Michael’s half of their partnership after receiving her recovery from Min Zhu. Min Zhu balked at the prospect of paying a middleman in settling for his daughter’s sexual services. Erin went along with his offer to pay most of her blood money under the table. She promised to pay her debts to Michael and David from that clandestine settlement. In the meantime, she borrowed more money from Michael’s friends and family to support her romance with an aging German pop musician, Blixa Bargeld. And once she got her money from Min, Erin cut off all communications with her creditors. In a futile attempt to forestall Michael’s complaint, anonymous threats named him a dead man on the behalves of WebEx and Min Zhu. The lawsuits settled three years later, on October 25th of last year. In the meantime, Michael’s father Isaak, plaintiff in a related lawsuit, has perished from an apartment fire of suspicious origins. Michael is poised to hound WebEx and the Zhus into the deepest circle of Hell.

Michael reflects upon his inadequacy to follow in the footsteps of Dante. Dante is the greatest poet since the classical age. Only Shakespeare comes close in modern history. For the grandeur of Dante’s moral vision, Shakespeare substitutes familiarity. His heroes are easier to take. Hamlet is a modern character because the excellence of his intellect is compromised by the setting of a third-rate Elizabethan revenge drama. Michael finds himself trapped in a postmodern travesty of Elsinore, populated with characters from an X-rated soap opera. “Du sublime au ridicule il n’ya qu’un pas.” By constantly commenting upon the single step separating the sublime from the ridiculous, Napoléon Bonaparte anticipated the cruel conclusion of his brilliant career. Michael’s career rests on the distinction between a gadfly and a horse’s arse. He doesn’t mind being a bit of both.

Michael is talking with David. His thoughts turn from sinners to saints. He recalls William James pausing to pick a fight with Friedrich Nietzsche in the course of discussing the value of saintliness in Lectures 14 and 15 of The Varieties of Religious Experience:

David is not sure what Nietzsche means. He has just lost his trial against a defense contractor. The defendant fired David’s client, Dr. Nira S., after six months of employment. Nira complained that she was dismissed for investigating fraud in the missile defense system that her employer was developing for the Pentagon. Her employer retorted that Nira was unfit for her duties. In her late fifties, Nira speaks in the high pitched cadences of a little girl. Since the early days of the third millennium, she has generated countless reams of legalistic paperwork advocating her whistleblower claims for hundreds of millions of dollars on behalf of the U.S. government. The U.S. government retorted by shutting down her qui tam actions on the grounds of national security. Nira believes that she has been blackballed since filing her lawsuit. It follows from her inability to find a job in her field despite having sent out more than 300 resumes. David has persevered with Nira’s claim for wrongful termination by the defense contractor. He has spent thousands of unpaid hours pursuing it on a contingent fee basis. He has no regrets. His country is being held hostage to a conglomerate of “red states”. Republican fraud must be exposed, even at the risk of ridicule.

Michael questions the notion of fraud being particular to the Republican administration. He ranks it among the classics of political revisionism, alongside with stealing the patrimony of Abraham Lincoln on behalf of the party of George Wallace. He cannot account for the malign amalgamation of mephitic bile and paint-blistering stupidity that contaminates otherwise gracious and thoughtful discourse of civilians finding themselves on the washed-out side of an electoral contest. Sore losers.

His doubt coalesced into certainty when David reported a fair outcome in dividing the spoils with his former partner. Through his conversations with John, Michael concluded that David and he were simply unwilling to follow and unable to lead. Both of them consigned themselves to solo practice. Contrariwise, David is uneasy with force and fraud concomitant with business leadership. Michael recalls accompanying David to a Palo Alto restaurant five years earlier. David went there to present Erin’s rape claims to her parents. Michael came along as David’s bodyguard. Both Erin and David were concerned about the likelihood of a violent reprisal. David and Michael arrived early and sat separately. Just mefore the Zhus walked in, David connected with Michael through their cell phones. Michael saw and heard what happened next.

Min Zhu came in with his wife Susan Xu. They greeted David and sat down at his table. Min expressed no surprise at Erin’s accusations of serial rape. He did not bother to deny her claims. Instead, he described his experiences in China during the Cultural Revolution. Min and Susan had been sent to a village for re-education. They struggled very hard just to survive. Min had prevailed in many fights against the villagers. He eventually made it to the U.S. as a graduate student at Stanford. He succeeded in building WebEx, a corporation already valued at over a billion dollars even before going public. Min was unperturbed by the prospect of losing everything. Such loss would be nothing in comparison to the hardships that he suffered in his youth. He looked forward to fighting for his life. He was prepared for the worst and resigned to the likelihood of being martyred by corrupt American justice. Susan said nothing. She heard Min’s litany many times before. Min was an expert at terrorizing his family. He did not do so well with someone his own size. Susan liked other men. She batted her eyelashes at David.

On their drive back to the San Jose airport, David recounted his impressions of Min and Susan. Min had the appearance of a crusty old crab. He was tough and ruthless. Susan acted weird. She started out by giving David the evil eye, then appeared to flirt with him. Engrossed by his story, David missed the freeway exit three times in a row. Michael suspects that in looking on Min Zhu’s face, David was as much smitten with wonder at his freedom from inner restraint as with awe at the energy of his outward performances. In witnessing Min Zhu’s deposition in his case a few months earlier, Michael was underwhelmed. He saw a badly dressed, prematurely aged man carping about his wayward daughter’s taste in fancy underwear. The comb-over winding around his forehead stood proxy for not fooling anyone. Min refused to address the child rape allegations. He will be unable to evade them in deposition for a libel lawsuit that WebEx has filed against Michael.

Michael is reluctant to join David in complaining about political uses of force and fraud. Partisan hyperbole fails by proving too much from supposing too little. Reciprocal application of Democratic invective to their makers fails only through an act of blind faith in their divine election. The human lot is to be ruled by liars and cheats. Political conscience is a connivance. Both parties lie and cheat on platforms dedicated to uplifting their benighted electorate. In the Republican case, their imperialist ambition has caused the winners to be loathed by their foreign inferiors. In the Democrat case, their domestic condescension has caused the losers to be rejected by their uncouth electorate. The Republicans propound agenda without nuance. The Democrats dither in nuance without agenda. Given these alternatives, Michael resents being called upon to choose between being hated by foreigners and being despised by his compatriots.

And yet, living in a time of the Fourth World War has its own rewards. Islamism is a fatal threat to democracy. Its menace is aggravated by disparities in the rates of population growth and memetic propagation. Failure to resist it is scarcely excused by the duplicity of administration or the incompetence of command. The litany of Western political fraud and war crimes cannot sustain liberal tolerance for Oriental atrocities. Babies have died in all wars, just and unjust. Propounding baby-killing as the epitome of political evil does not decide the question of justice in rescuing the next generation from tyranny. In this setting, pacifists succeed only in relinquishing their capacity to oppose evil with force to their social inferiors. Justice comes from strife. It cannot emerge from nurturing dupes in the service of knaves. There will be no peace in the Middle East as long as the Jewish state stands as its sole democracy. There will be no security in the United States until and unless we succeed at Islamic nation building.

Meanwhile, as Dante has vividly shown, amusement and instruction of the highest order can come from the lowest of constituents. Michael recalls the old American saying that Robert Stone coined in A Flag for Sunrise: “Mickey Mouse will see you dead.”

Michael is having dinner with his friend David A. David is a trial lawyer. He is a member of the plaintiffs’ bar. He makes political contributions to the Democrats. David roots for the underdog. He represents Michael against the libel lawsuit by WebEx. WebEx is complaining about Michael’s public account of their failed coverup of child rape by their founder Min Zhu. Min Zhu’s sexual abuse of his daughter Erin is a matter of public record. The outed daughter rapist has since lost his job as WebEx President. He has testified under oath about his plans to “retire” altogether.

Michael credits himself with bringing his degeneracy to the attention of WebEx employees and investors. He thinks of Dante Alighieri encountering in Canto 15 of the Inferno his old master Brunetto Latini.

Brunetto’s sin is sodomy. Dante’s testimony is the only evidence of Brunetto’s sodomite proclivities that we possess. Dante’s outing of sexual perversion is the first such instance that we know. His pen permanently degrades courtly scholar Brunetto to a grotesque apparition.

The lowest among incontinent sinners, sodomites are punished in the seventh circle of Hell for their violent love. It is violence of the worst kind, violence committed against God:

| Puossi far forza nella deitade, col cor negando e bestemmiando quella, e spregiando natura e sua bontade; |

One can be violent against the Godhead, one’s heart denying and blaspheming Him and scorning nature and the good in her; |

| e però lo minor giron suggella del segno suo e Soddoma e Caorsa e chi, spregiando Dio col cor, favella. |

so, with its sign, the smallest ring has sealed both Sodom and Cahors and all of those who speak in passionate contempt of God. |

| ― Inferno, Canto 11, 46-51 | ― translated by Allen Mandelbaum |

In these days prevailed the horrible nuisance of the Caursines to such a degree that there was hardly any one in all England, especially among the bishops, who was not caught in their net. Even the king himself was held indebted to them in an uncalculable sum of money. For they circumvented the needy in their necessities, cloaking their usury under the show of trade, and pretending not to know that whatever is added to the principal is usury, under whatever name it may be called. For it is manifest that their loans lie not in the path of charity, inasmuch as they do not hold out a helping hand to the poor to relieve them, but to deceive them; not to aid others in their starvation, but to gratify their own covetousness; seeing that the motive stamps our every deed.Usurers hold the social ends of labor in contempt by reaping its economic benefits while avoiding production. Sodomites hold the natural ends of sex in contempt by reaping its venereal pleasures while precluding human generation. Dante consigns sodomites to perpetual motion under falling fire and over an arid sandy plain “that banishes all green things from its bed.” (See Inferno, Canto 14, 7-15.) Deeper yet, in the Eighth Circle, reside the falsifiers.

— translated by J.A. Giles

In their midst Dante finds Myrrha, the incestuous daughter, “she who loved her father past the limits of just love”, she who “came to sin with him by falsely taking another’s shape upon herself”, whose tale came to Dante by way of Ovid, from the Tenth Book of his Metamorphoses.

Below her, avoided by Dante amidst the giants in the Ninth Circle, resides the giant Tityus, whose mere attempt to rape Latona, mother of Apollo and Diana, causes his eternal torment by a vulture continuously feeding on his constantly regenerating liver.

The poets of classical antiquity painted vivid images of Tituys’ punishment:

| Nec non et Tityon, Terrae omniparentis alumnum, cernere erat, per tota novem cui iubera corpus porrigitur, rostroque immanis voltur obunco immortale iecur tondens fecundaque poenis viscera, rimaturque epulis, habitatque sub alto pectore, nec fibris requies datur ulla renatis. |

There Tityus was to see, who took his birth From heav’n, his nursing from the foodful earth. Here his gigantic limbs, with large embrace, Infold nine acres of infernal space. A rav’nous vulture, in his open’d side, Her crooked beak and cruel talons tried; Still for the growing liver digg’d his breast; The growing liver still supplied the feast; Still are his entrails fruitful to their pains: Th’ immortal hunger lasts, th’ immortal food remains. |

| ― Virgil, Aeneid, VI.595-600 | ― translated by John Dryden |

| Quam simul agnorunt inter caliginis umbras, surrexere deae. Sedes scelerata vocatur: viscera praebebat Tityos lanianda novemque iugeribus distentus erat; tibi, Tantale, nullae deprenduntur aquae, quaeque inminet, effugit arbor |

This is the place of woe, here groan the dead; Huge Tityus o’er nine acres here is spread. Fruitful for pain th’ immortal liver breeds, Still grows, and still th’ insatiate vulture feeds. Poor Tantalus to taste the water tries, But from his lips the faithless water flies: Then thinks the bending tree he can command, The tree starts backwards, and eludes his hand. |

| ― Ovid, Metamorphoses, IV.455-459 | ― translated by John Dryden |

| «La frode, ond’ogne coscienza è morsa, può l’omo usare in colui che ‘n lui fida e in quel che fidanza non imborsa. |

“Now fraud, that eats away at every conscience, is practiced by a man against another who trusts in him, or one who has no trust. |

| Questo modo di retro par ch’incida pur lo vinco d’amor che fa natura; onde nel cerchio secondo s’annida |

This latter way seems only to cut off the bond of love that nature forges; thus, nestled within the second circle are: |

| ipocresia, lusinghe e chi affattura, falsità, ladroneccio e simonia, ruffian, baratti e simile lordura. |

hypocrisy and flattery, sorcerers, and falsifiers, simony, and theft, and barrators and panders and like trash. |

| Per l’altro modo quell’amor s’oblia che fa natura, e quel ch’è poi aggiunto, di che la fede spezial si cria; |

But in the former way of fraud, not only the love that nature forges is forgotten, but added love that builds a special trust; |

| onde nel cerchio minore, ov’è ‘l punto de l’universo in su che Dite siede, qualunque trade in etterno è consunto». |

thus, in the tightest circle, where there is the universe’s center, seat of Dis, all traitors are consumed eternally.” |

| ― Inferno, Canto 11, 52-66 | ― translated by Allen Mandelbaum |

And so, in Cocytus, inside the fourth ring of the ninth circle of Dante’s Inferno, traitors against their benefactors lie immobilized, totally covered in ice:

| Noi passammo oltre, là ‘ve la gelata ruvidamente un’altra gente fascia, non volta in giù, ma tutta riversata. |

We passed beyond, where frozen water wraps ― a rugged covering ― still other sinners, who were not bent, but flat upon their backs. |

| Lo pianto stesso lì pianger non lascia, e ‘l duol che truova in su li occhi rintoppo, si volge in entro a far crescer l’ambascia; |

Their very weeping there won’t let them weep, and grief that finds a barrier in their eyes turns inward to increase their agony; |

| ché le lagrime prime fanno groppo, e sì come visiere di cristallo, riempion sotto ‘l ciglio tutto il coppo. |

because their first tears freeze into a cluster, and, like a crystal visor, fill up all the hollow that is underneath the eyebrow. |

| E avvegna che, sì come d’un callo, per la freddura ciascun sentimento cessato avesse del mio viso stallo, |

And though, because of cold, my every sense had left its dwelling in my face, just as a callus has no feeling, nonetheless, |

| già mi parea sentire alquanto vento: per ch’io: «Maestro mio, questo chi move? non è qua giù ogne vapore spento?». |

I seemed to feel some wind now, and I said: “My master, who has set this gust in motion? For isn’t every vapor quenched down here?” |

| Ond’elli a me: «Avaccio sarai dove di ciò ti farà l’occhio la risposta, veggendo la cagion che ‘l fiato piove». |

And he to me: “You soon shall be where your own eye will answer that, when you shall see the reason why this wind blasts from above.” |

| E un de’ tristi de la fredda crosta gridò a noi: «O anime crudeli, tanto che data v’è l’ultima posta, |

And one of those sad sinners in the cold crust, cried to us: “O souls who are so cruel that this last place has been assigned to you, |

| levatemi dal viso i duri veli, sì ch’io sfoghi ‘l duol che ‘l cor m’impregna, un poco, pria che ‘l pianto si raggeli». |

take off the hard veils from my face so that I can release the suffering that fills my heart before lament freezes again.” |

| Per ch’io a lui: «Se vuo’ ch’i’ ti sovvegna, dimmi chi se’, e s’io non ti disbrigo, al fondo de la ghiaccia ir mi convegna». |

To which I answered: “If you’d have me help you, then tell me who you are; if I don’t free you, may I go to the bottom of the ice.” |

| Rispuose adunque: «I’ son frate Alberigo; i’ son quel da le frutta del mal orto, che qui riprendo dattero per figo». |

He answered then: “I am Fra Alberigo, the one who tended fruits in a bad garden, and here my figs have been repaid with dates.” |

| «Oh!», diss’io lui, «or se’ tu ancor morto?». Ed elli a me: «Come ‘l mio corpo stea nel mondo sù, nulla scienza porto. |

“But then,” I said, “are you already dead?” And he to me: “I have no knowledge of my body’s fate within the world above. |

| Cotal vantaggio ha questa Tolomea, che spesse volte l’anima ci cade innanzi ch’Atropòs mossa le dea. |

For Ptolomea has this privilege: quite frequently the soul falls here before it has been thrust away by Atropos. |

| E perché tu più volentier mi rade le ‘nvetriate lagrime dal volto, sappie che, tosto che l’anima trade |

And that you may with much more willingness scrape these glazed tears from off my face, know this: as soon as any soul becomes a traitor, |

| come fec’io, il corpo suo l’è tolto da un demonio, che poscia il governa mentre che ‘l tempo suo tutto sia vòlto. |

as I was, then a demon takes its body away ― and keeps that body in his power until its years have run their course completely. |

| Ella ruina in sì fatta cisterna; e forse pare ancor lo corpo suso de l’ombra che di qua dietro mi verna. |

The soul falls headlong, down into this cistern; and up above, perhaps, there still appears the body of the shade that winters here |

| Tu ‘l dei saper, se tu vien pur mo giuso: elli è ser Branca Doria, e son più anni poscia passati ch’el fu sì racchiuso». |

behind me; you must know him, if you’ve just come down; he is Ser Branca Doria; for many years he has been thus pent up.” |

| «Io credo», diss’io lui, «che tu m’inganni; ché Branca Doria non morì unquanche, e mangia e bee e dorme e veste panni». |

I said to him: “I think that you deceive me, for Branca Doria is not yet dead; he eats and drinks and sleeps and puts on clothes.” |

| «Nel fosso sù», diss’el, «de’ Malebranche, là dove bolle la tenace pece, non era ancor giunto Michel Zanche, |

”There in the Malebranche’s ditch above, where sticky pitch boils up, Michele Zanche had still not come,” he said to me, “when this one ― |

| che questi lasciò il diavolo in sua vece nel corpo suo, ed un suo prossimano che ‘l tradimento insieme con lui fece. |

together with a kinsman, who had done the treachery together with him ― left a devil in his stead inside his body. |

| Ma distendi oggimai in qua la mano; aprimi li occhi». E io non gliel’apersi; e cortesia fu lui esser villano. |

But now reach out your hand; open my eyes.” And yet I did not open them for him; and it was courtesy to show him rudeness. |

| Ahi Genovesi, uomini diversi d’ogne costume e pien d’ogne magagna, perché non siete voi del mondo spersi? |

Ah, Genoese, a people strange to every constraint of custom, full of all corruption, why have you not been driven from the world? |

| Ché col peggiore spirto di Romagna trovai di voi un tal, che per sua opra in anima in Cocito già si bagna, |

For with the foulest spirit of Romagna, I found one of you such that, for his acts, in soul he bathes already in Cocytus |

| e in corpo par vivo ancor di sopra. | and up above appears alive, in body. |

| ― Inferno, Canto 33, 89-157 | ― translated by Allen Mandelbaum |

A child in her parents’ home benefits from the most sacred bond of hospitality. Conjured forth by sex, she enters their household in a state of utter dependence upon her hosts. Michael reflects on the character of a man that violently betrays this bond, exploiting her dependence for the sake of expending his lust. In the character of unnatural fatherhood, distorted by violent lust, the daughter rapist descends from the high tragedy of Myrrha making her fatal unfilial advances to unwitting Cinyras, to the common realm of the rustic folktale, ill suited to a civilized setting. He wonders what possessed him to invest his labor in an enterprise conceived between his former best friend and her child rapist father. He cannot fathom his own choices at the turn of the millennium.

Michael met David in 1999. At that time, Michael was in a business partnership with his ex-girlfriend Erin Zhu. They were looking for corporate counsel to assist them in the deal Erin made with WebEx, an Internet startup co-founded by her father. David came recommended by Michael’s friend Lenny R. Lenny graduated from Caltech with a PhD in applied mathematics. He was running his own technology startup after buying out his former partner. Lenny’s advice was to get a trial lawyer, because sooner or later, all partnerships wound up in litigation. His prophecy fulfilled itself within the year. WebEx breached their contract with Erin and Michael. Instead of complaining on business grounds, Erin hired their friend David on a token contingent fee basis of 2.5%, to sue her father for childhood sexual abuse. She promised to buy out Michael’s half of their partnership after receiving her recovery from Min Zhu. Min Zhu balked at the prospect of paying a middleman in settling for his daughter’s sexual services. Erin went along with his offer to pay most of her blood money under the table. She promised to pay her debts to Michael and David from that clandestine settlement. In the meantime, she borrowed more money from Michael’s friends and family to support her romance with an aging German pop musician, Blixa Bargeld. And once she got her money from Min, Erin cut off all communications with her creditors. In a futile attempt to forestall Michael’s complaint, anonymous threats named him a dead man on the behalves of WebEx and Min Zhu. The lawsuits settled three years later, on October 25th of last year. In the meantime, Michael’s father Isaak, plaintiff in a related lawsuit, has perished from an apartment fire of suspicious origins. Michael is poised to hound WebEx and the Zhus into the deepest circle of Hell.

Michael reflects upon his inadequacy to follow in the footsteps of Dante. Dante is the greatest poet since the classical age. Only Shakespeare comes close in modern history. For the grandeur of Dante’s moral vision, Shakespeare substitutes familiarity. His heroes are easier to take. Hamlet is a modern character because the excellence of his intellect is compromised by the setting of a third-rate Elizabethan revenge drama. Michael finds himself trapped in a postmodern travesty of Elsinore, populated with characters from an X-rated soap opera. “Du sublime au ridicule il n’ya qu’un pas.” By constantly commenting upon the single step separating the sublime from the ridiculous, Napoléon Bonaparte anticipated the cruel conclusion of his brilliant career. Michael’s career rests on the distinction between a gadfly and a horse’s arse. He doesn’t mind being a bit of both.

Michael is talking with David. His thoughts turn from sinners to saints. He recalls William James pausing to pick a fight with Friedrich Nietzsche in the course of discussing the value of saintliness in Lectures 14 and 15 of The Varieties of Religious Experience:

The most inimical critic of the saintly impulses whom I know is Nietzsche. He contrasts them with the worldly passions as we find these embodied in the predaceous military character, altogether to the advantage of the latter. Your born saint, it must be confessed, has something about him which often makes the gorge of a carnal man rise, so it will be worth while to consider the contrast in question more fully.

Dislike of the saintly nature seems to be a negative result of the biologically useful instinct of welcoming leadership, and glorifying the chief of the tribe. The chief is the potential, if not the actual tyrant, the masterful, overpowering man of prey. We confess our inferiority and grovel before him. We quail under his glance, and are at the same time proud of owning so dangerous a lord. Such instinctive and submissive hero-worship must have been indispensable in primeval tribal life. In the endless wars of those times, leaders were absolutely needed for the tribe’s survival. If there were any tribes who owned no leaders, they can have left no issue to narrate their doom. The leaders always had good consciences, for conscience in them coalesced with Will, and those who looked on their face were as much smitten with wonder at their freedom from inner restraint as with awe at the energy of their outward performances.

Compared with these beaked and taloned graspers of the world, saints are herbivorous animals, tame and harmless barn-yard poultry. There are saints whose beard you may, if you ever care to, pull with impunity. Such a man excites no thrills of wonder veiled in terror; his conscience is full of scruples and returns; he stuns us neither by his inward freedom nor his outward power; and unless he found within us an altogether different faculty of admiration to appeal to, we should pass him by with contempt.

In point of fact, he does appeal to a different faculty. Reenacted in human nature is the fable of the wind, the sun, and the traveler. The sexes embody the discrepancy. The woman loves the man the more admiringly the stormier he shows himself, and the world deifies its rulers the more for being willful and unaccountable. But the woman in turn subjugates the man by the mystery of gentleness in beauty, and the saint has always charmed the world by something similar. Mankind is susceptible and suggestible in opposite directions, and the rivalry of influences is unsleeping. The saintly and the worldly ideal pursue their feud in literature as much as in real life.

For Nietzsche the saint represents little but sneakingness and slavishness. He is the sophisticated invalid, the degenerate par excellence, the man of insufficient vitality. His prevalence would put the human type in danger.“The sick are the greatest danger for the well. The weaker, not the stronger, are the strong’s undoing. It is not fear of our fellow-man, which we should wish to see diminished; for fear rouses those who are strong to become terrible in turn themselves, and preserves the hard-earned and successful type of humanity. What is to be dreaded by us more than any other doom is not fear, but rather the great disgust, not fear, but rather the great pity ― disgust and pity for our human fellows.... The morbid are our greatest peril ― not the ‘bad’ men, not the predatory beings. Those born wrong, the miscarried, the broken ― they it is, the weakest, who are undermining the vitality of the race, poisoning our trust in life, and putting humanity in question. Every look of them is a sigh ― ‘Would I were something other! I am sick and tired of what I am.’ In this swamp-soil of self-contempt, every poisonous weed flourishes, and all so small, so secret, so dishonest, and so sweetly rotten. Here swarm the worms of sensitiveness and resentment; here the air smells odious with secrecy, with what is not to be acknowledged; here is woven endlessly the net of the meanest of conspiracies, the conspiracy of those who suffer against those who succeed and are victorious; here the very aspect of the victorious is hated ― as if health, success, strength, pride, and the sense of power were in themselves things vicious, for which one ought eventually to make bitter expiation. Oh, how these people would themselves like to inflict the expiation, how they thirst to be the hangmen! And all the while their duplicity never confesses their hatred to be hatred.” (Zur Genealogie der Moral, Dritte Abhandlung, §14. I have abridged, and in one place transposed, a sentence.)Poor Nietzsche’s antipathy is itself sickly enough, but we all know what he means, and he expresses well the clash between the two ideals. The carnivorous-minded “strong man,” the adult male and cannibal, can see nothing but mouldiness and morbidness in the saint’s gentleness and self-severity, and regards him with pure loathing. The whole feud revolves essentially upon two pivots: Shall the seen world or the unseen world be our chief sphere of adaptation? and must our means of adaptation in this seen world be aggressiveness or non-resistance?

The debate is serious. In some sense and to some degree both worlds must be acknowledged and taken account of; and in the seen world both aggressiveness and non-resistance are needful. It is a question of emphasis, of more or less. Is the saint’s type or the strong-man’s type the more ideal?

David is not sure what Nietzsche means. He has just lost his trial against a defense contractor. The defendant fired David’s client, Dr. Nira S., after six months of employment. Nira complained that she was dismissed for investigating fraud in the missile defense system that her employer was developing for the Pentagon. Her employer retorted that Nira was unfit for her duties. In her late fifties, Nira speaks in the high pitched cadences of a little girl. Since the early days of the third millennium, she has generated countless reams of legalistic paperwork advocating her whistleblower claims for hundreds of millions of dollars on behalf of the U.S. government. The U.S. government retorted by shutting down her qui tam actions on the grounds of national security. Nira believes that she has been blackballed since filing her lawsuit. It follows from her inability to find a job in her field despite having sent out more than 300 resumes. David has persevered with Nira’s claim for wrongful termination by the defense contractor. He has spent thousands of unpaid hours pursuing it on a contingent fee basis. He has no regrets. His country is being held hostage to a conglomerate of “red states”. Republican fraud must be exposed, even at the risk of ridicule.

Michael questions the notion of fraud being particular to the Republican administration. He ranks it among the classics of political revisionism, alongside with stealing the patrimony of Abraham Lincoln on behalf of the party of George Wallace. He cannot account for the malign amalgamation of mephitic bile and paint-blistering stupidity that contaminates otherwise gracious and thoughtful discourse of civilians finding themselves on the washed-out side of an electoral contest. Sore losers.

| Né vi sbigottisca quella antichità del sangue che ei ci rimproverano; perché tutti gli uomini, avendo avuto uno medesimo principio, sono ugualmente antichi, e da la natura sono stati fatti ad uno modo. Spogliateci tutti ignudi: voi ci vedrete simili, rivestite noi delle veste loro ed eglino delle nostre: noi senza dubio nobili ed eglino ignobili parranno; perché solo la povertà e le ricchezze ci disaguagliano. […] Ma se voi noterete il modo del procedere degli uomini, vedrete tutti quelli che a ricchezze grandi e a grande potenza pervengono o con frode o con forza esservi pervenuti; e quelle cose, di poi, ch’eglino hanno o con inganno o con violenza usurpate, per celare la bruttezza dello acquisto, quello sotto falso titolo di guadagno adonestano. ― Niccolò Machiavelli, Istorie fiorentine, libro terzo, 13 |

Be not deceived about that antiquity of blood by which they exalt themselves above us; for all men having had one common origin, are all equally ancient, and nature has made us all after one fashion. Strip us naked, and we shall all be found alike. Dress us in their clothing, and they in ours, we shall appear noble, they ignoble—for poverty and riches make all the difference. […] If you only notice human proceedings, you may observe that all who attain great power and riches, make use of either force or fraud; and what they have acquired either by deceit or violence, in order to conceal the disgraceful methods of attainment, they endeavor to sanctify with the false title of honest gains. ― History of Florence |

His doubt coalesced into certainty when David reported a fair outcome in dividing the spoils with his former partner. Through his conversations with John, Michael concluded that David and he were simply unwilling to follow and unable to lead. Both of them consigned themselves to solo practice. Contrariwise, David is uneasy with force and fraud concomitant with business leadership. Michael recalls accompanying David to a Palo Alto restaurant five years earlier. David went there to present Erin’s rape claims to her parents. Michael came along as David’s bodyguard. Both Erin and David were concerned about the likelihood of a violent reprisal. David and Michael arrived early and sat separately. Just mefore the Zhus walked in, David connected with Michael through their cell phones. Michael saw and heard what happened next.

Min Zhu came in with his wife Susan Xu. They greeted David and sat down at his table. Min expressed no surprise at Erin’s accusations of serial rape. He did not bother to deny her claims. Instead, he described his experiences in China during the Cultural Revolution. Min and Susan had been sent to a village for re-education. They struggled very hard just to survive. Min had prevailed in many fights against the villagers. He eventually made it to the U.S. as a graduate student at Stanford. He succeeded in building WebEx, a corporation already valued at over a billion dollars even before going public. Min was unperturbed by the prospect of losing everything. Such loss would be nothing in comparison to the hardships that he suffered in his youth. He looked forward to fighting for his life. He was prepared for the worst and resigned to the likelihood of being martyred by corrupt American justice. Susan said nothing. She heard Min’s litany many times before. Min was an expert at terrorizing his family. He did not do so well with someone his own size. Susan liked other men. She batted her eyelashes at David.

On their drive back to the San Jose airport, David recounted his impressions of Min and Susan. Min had the appearance of a crusty old crab. He was tough and ruthless. Susan acted weird. She started out by giving David the evil eye, then appeared to flirt with him. Engrossed by his story, David missed the freeway exit three times in a row. Michael suspects that in looking on Min Zhu’s face, David was as much smitten with wonder at his freedom from inner restraint as with awe at the energy of his outward performances. In witnessing Min Zhu’s deposition in his case a few months earlier, Michael was underwhelmed. He saw a badly dressed, prematurely aged man carping about his wayward daughter’s taste in fancy underwear. The comb-over winding around his forehead stood proxy for not fooling anyone. Min refused to address the child rape allegations. He will be unable to evade them in deposition for a libel lawsuit that WebEx has filed against Michael.

Michael is reluctant to join David in complaining about political uses of force and fraud. Partisan hyperbole fails by proving too much from supposing too little. Reciprocal application of Democratic invective to their makers fails only through an act of blind faith in their divine election. The human lot is to be ruled by liars and cheats. Political conscience is a connivance. Both parties lie and cheat on platforms dedicated to uplifting their benighted electorate. In the Republican case, their imperialist ambition has caused the winners to be loathed by their foreign inferiors. In the Democrat case, their domestic condescension has caused the losers to be rejected by their uncouth electorate. The Republicans propound agenda without nuance. The Democrats dither in nuance without agenda. Given these alternatives, Michael resents being called upon to choose between being hated by foreigners and being despised by his compatriots.

And yet, living in a time of the Fourth World War has its own rewards. Islamism is a fatal threat to democracy. Its menace is aggravated by disparities in the rates of population growth and memetic propagation. Failure to resist it is scarcely excused by the duplicity of administration or the incompetence of command. The litany of Western political fraud and war crimes cannot sustain liberal tolerance for Oriental atrocities. Babies have died in all wars, just and unjust. Propounding baby-killing as the epitome of political evil does not decide the question of justice in rescuing the next generation from tyranny. In this setting, pacifists succeed only in relinquishing their capacity to oppose evil with force to their social inferiors. Justice comes from strife. It cannot emerge from nurturing dupes in the service of knaves. There will be no peace in the Middle East as long as the Jewish state stands as its sole democracy. There will be no security in the United States until and unless we succeed at Islamic nation building.

Meanwhile, as Dante has vividly shown, amusement and instruction of the highest order can come from the lowest of constituents. Michael recalls the old American saying that Robert Stone coined in A Flag for Sunrise: “Mickey Mouse will see you dead.”