[Recent Entries][Archive][Friends][User Info]

| Time | Text |

|---|---|

| 06:14 pm [Link] |

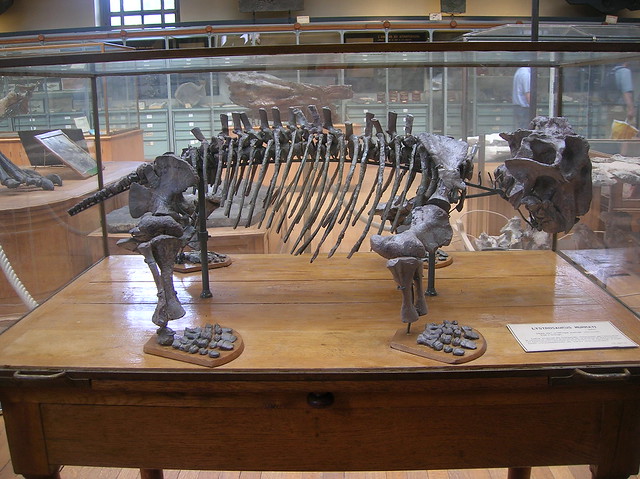

Lystrosaurus Листрозавры (Lystrosaurus) — раннетриасовые дицинодонты. Листрозавры были среди немногих дицинодонтов, выживших во время пермотриасового кризиса. От других дицинодонтов их отличает высокий укороченный череп с вынесенными наверх ноздрями и глазами. Как и у многих других дицинодонтов, у листрозавров из всех зубов сохранились лишь два верхних клыка. Челюсти, вероятно, были одеты роговым клювом. Ноги короткие и массивные. Листрозавров долгое время считали полуводными животными, вроде гиппопотамов. Сейчас предполагают, что они жили в полупустынях раннего триаса и выкапывали пищу (возможно, корни растений) из земли с помощью клыков. Остатки листрозавров были впервые найдены в Южной Африке в 50-х годах XIX века. В настоящее время известно, что листрозавры населяли в самом начале триаса всю Пангею. Они были доминирующими растительноядными той эпохи, дав своё имя первой зоне эпохи нижнего триаса (зона Lystrosaurus). Их кости обнаружены в Антарктике и на севере России, а также в Китае и Индии. Всего описаны 13—14 видов. Длина черепа у разных видов от 12 до 40 см, длина тела могла достигать 2 м. Листрозавры — возможные предки крупных триасовых дицинодонтов — каннемейерий. Lystrosaurus was a pig-sized dicynodont therapsid, typically about 3 feet (0.9 m) long and weighing about 200 pounds (90 kg). Unlike other therapsids, dicynodonts had very short snouts and no teeth except for the tusk-like upper canines. Dicynodonts are generally thought to have had horny beaks like those of turtles, for shearing off pieces of vegetation which were then ground on a horny secondary palate when the mouth was closed. The jaw joint was weak and moved backwards and forwards with a shearing action, instead of the more common sideways or up and down movements. It is thought that the jaw muscles were attached unusually far forward on the skull and took up a lot of space on the top and back of the skull. As a result the eyes were set high and well forward on the skull, and the face was short. Features of the skeleton indicate that Lystrosaurus moved with a semi-sprawling gait. The lower rear corner of the scapula (shoulder blade) was strongly ossified (built of strong bone), which suggests that movement of the scapula contributed to the stride length of the forelimbs and reduced the sideways flexing of the body. The five sacral vertebrae were massive but not fused to each other and to the pelvis, making the back more rigid and reducing sideways flexing while the animal was walking. Therapsids with fewer than five sacral vertebrae are thought to have had sprawling limbs, like those of modern lizards. In dinosaurs and mammals, which have erect limbs, the sacral vertebrae are fused to each other and to the pelvis. A buttress above each acetabulum (hip socket) is thought to have prevented dislocation of the femur (thigh bone) while Lystrosaurus was walking with a semi-sprawling gait. The forelimbs of Lystrosaurus were massive, and Lystrosaurus is thought to have been a powerful burrower. Most Lystrosaurus fossils have been found in the Balfour and Katburg Formations of the Karoo region, which is mostly in South Africa; these specimens offer the best prospects of identifying species because they are the most numerous and have been studied for the longest time. As so often with fossils, there is debate in the paleontological community as to exactly how many species have been found in the Karoo. Studies from the 1930s to 1970s suggested a large number (23 in one case). However, by the 1980s and 1990s, only six species were recognized in the Karoo: L. curvatus, L. platyceps, L. oviceps, L. maccaigi, L. murrayi, and L. declivis. A study in 2011 reduced that number to four, treating the fossils previously labeled as L. platyceps and L. oviceps as members of L. curvatus. L. maccaigi is the largest and apparently most specialized species, while L. curvatus was the least specialized. A Lystrosaurus-like fossil, Kwazulusaurus shakai, has also been found in South Africa. Although not assigned to the same genus, K. shakai is very similar to L. curvatus. Some paleontologists have therefore proposed that K. shakai was possibly an ancestor of or closely related to the ancestors of L. curvatus, while L. maccaigi arose from a different lineage. L. maccaigi is found only in sediments from the Permian period, and apparently did not survive the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Its specialized features and sudden appearance in the fossil record without an obvious ancestor may indicate that it immigrated into the Karoo from an area in which Late Permian sediments have not been found. L. curvatus is found in a relatively narrow band of sediments from shortly before and after the extinction, and can be used as an approximate marker for the boundary between the Permian and Triassic periods. A skull identified as L. curvatus has been found in late Permian sediments from Zambia. For many years it had been thought that there were no Permian specimens of L. curvatus in the Karoo, which led to suggestions that L. curvatus immigrated from Zambia into the Karoo. However, a re-examination of Permian specimens in the Karoo has identified some as L. curvatus, and there is no need to assume immigration. L. murrayi and L. declivis are found only in Permian sediments. Lystrosaurus georgi fossils have been found in the Earliest Triassic sediments of the Moscow Basin in Russia. It was probably closely related to the African Lystrosaurus curvatus, which is regarded as one of the least specialized species and has been found in very Late Permian and very Early Triassic sediments. Lystrosaurus is notable for dominating southern Pangaea during the Early Triassic for millions of years. At least one unidentified species of this genus survived the end-Permian mass extinction and, in the absence of predators and of herbivorous competitors, went on to thrive and re-radiate into a number of species within the genus, becoming the most common group of terrestrial vertebrates during the Early Triassic; for a while 95% of land vertebrates were Lystrosaurus. This is the only time that a single species or genus of land animal dominated the Earth to such a degree. A few other Permian therapsid genera also survived the mass extinction and appear in Triassic rocks—the therocephalians Tetracynodon, Moschorhinus and Ictidosuchoides—but do not appear to have been abundant in the Triassic; complete ecological recovery took 30 million years, spanning the Early and Middle Triassic. Several attempts have been made to explain why Lystrosaurus survived the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the "mother of all mass extinctions", and why it dominated Early Triassic fauna to such an unprecedented extent: 1) One of the more recent theories is that the Permian–Triassic extinction event reduced the atmosphere's oxygen content and increased its carbon dioxide content, so that many terrestrial species died out because they found breathing too difficult. It has therefore been suggested that Lystrosaurus survived and became dominant because its burrowing life-style made it able to cope with an atmosphere of "stale air", and that specific features of its anatomy were part of this adaptation: a barrel chest that accommodated large lungs, short internal nostrils that facilitated rapid breathing, and high neural spines (projections on the dorsal side of the vertebrae) that gave greater leverage to the muscles that expanded and contracted its chest. However, there are weaknesses in all these points: the chest of Lystrosaurus was not significantly larger in proportion to its size than in other dicynodonts that became extinct; although Triassic dicynodonts appear to have had longer neural spines than their Permian counter-parts, this feature may be related to posture, locomotion or even body size rather than respiratory efficiency; L. murrayi and L. declivis are much more abundant than other Early Triassic burrowers such as Procolophon or Thrinaxodon. 2) The suggestion that Lystrosaurus was helped to survive and dominate by being semi-aquatic has a similar weakness: although amphibians become more abundant in the Karoo's Triassic sediments, they were much less numerous than L. murrayi and L. declivis. 3) The most specialized and the largest animals are at higher risk in mass extinctions; this may explain why the unspecialized L. curvatus survived while the larger and more specialized L. maccaigi perished along with all the other large Permian herbivores and carnivores. Although Lystrosaurus generally looks adapted to feed on plants similar to Dicroidium, which dominated the Early Triassic, the larger size of L. maccaigi may have forced it to rely on the larger members of the Glossopteris flora, which did not survive the end-Permian extinction. 4) Only the 1.5 metres (4.9 ft)–long therocephalian Moschorhinus and the large archosauriform Proterosuchus appear large enough to have preyed on the Triassic Lystrosaurus species, and this shortage of predators may have been responsible for a Lystrosaurus population boom in the Early Triassic. 5) Perhaps the survival of Lystrosaurus was simply a matter of luck.

Репродукции (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10):

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8):

|

| Reply: | |