[Recent Entries][Archive][Friends][User Info]

Below are the 18 most recent journal entries recorded in the "Сообщество, посвящённое ра" journal:| May 17th, 2014 | |

|---|---|

| 01:52 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

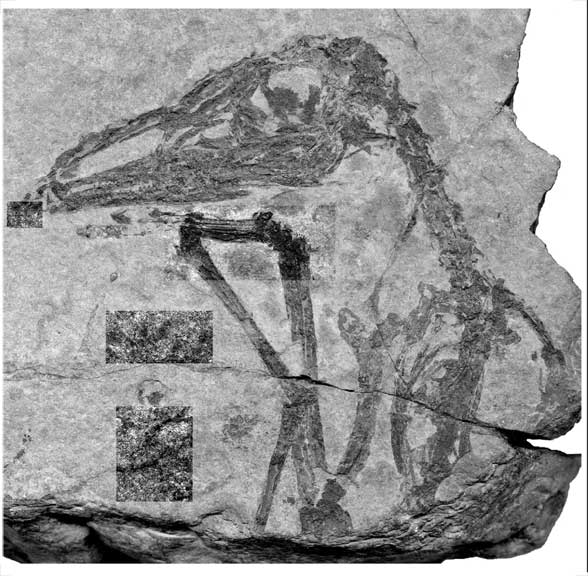

Dendrorhynchoides Dendrorhynchoides was a genus of anurognathid pterosaur containing species known from the Early Cretaceous (early Aptian) Yixian Formation, discovered near Beipiao, Chaoyang, Liaoning, China, and from Middle Jurassic Tiaojishan Formation of Qinglong, northern Hebei Province, China. The holotype of the type species was found in the Jianshangou Bed of the Yixian Formation, dated to about 124.6 million years old. However, Lü and Hone (2012) considered it possible that the holotype of D. curvidentatus was actually found in the Middle Jurassic deposits; the authors note that all other Chinese anurognathids are Jurassic in age, and that Jeholopterus was also initially thought to be a Cretaceous taxon until subsequent studies established it to be from the Jurassic. The genus was in 1998 first named Dendrorhynchus by Ji Shu'an and Ji Qiang, but that name proved to be preoccupied by a nemertean parasitic worm named in 1920 by David Keilin. It was therefore renamed in 1999. The type species is Dendrorhynchoides curvidentatus. The genus name is derived from Greek dendron, "tree" and rhynkhos, "snout" in reference to it being assumed a tree-dweller and presumed a close relative of Rhamphorhynchus. The specific name means "curved-toothed" in Latin. A second species, D. mutoudengensis, was described in 2012. The genus is based on holotype GMV2128, a fossil originally discovered around 1995 and obtained by science from illegal fossil dealers who first prepared it. It consists of a near-complete skeleton of a subadult individual and is crushed. Most elements are present, exceptions include the sternum, the tail end, sacrals and the fourth phalanx of the wing finger. Of the type specimen, most parts of the skull have become detached so that its shape is difficult to determine, but it was generally short and broad. Eleven teeth have been preserved scattered throughout the matrix, that are recurved with a broader base and have a length of three millimetres. The authors identified lower jaws with a preserved length of fifteen millimetres. The cervical vertebrae are short and broad. Six dorsal vertebrae have been preserved, nine ribs and six belly ribs at the left side. The tail has a preserved length of five centimetres, but part of this is accounted for by a section that might have been added to enhance the value of the fossil. The tail vertebrae at the base, the authenticity of which is certain, are short. The wings are relatively short. The humerus is robustly built but elongated with a length of 27 millimetres. The ulna is 35.5 millimetres long. The metacarpals are short with seven millimetres length for the first three, 9.3 millimetres for the fourth wing-bearing metacarpal. The first three fingers are well developed with the first having an elongated first phalanx. They bear short but sharp claws. The first phalanx of the fourth, wing, finger has a length of 44.5, the second of 35.6 millimetres. The size of the third cannot be established because of damage. A short and slender pteroid, 5.9 millimetres long, points towards the elbow. The wingspan is about forty centimetres, making Dendrorhynchoides one of the smallest known pterosaurs The tibia has a length of 26.7 millimetres and is about a third longer than the femur. The fibula is reduced, reaching about half-way downwards along the tibia shaft. The foot is long with the metatarsals having a length of 12.1 millimetres. The fifth toe is elongated. Because of the presumed long tail, the authors rejected a placement within the Anurognathidae and classified it instead as a long-tailed rhamphorhynchid, mainly in view of the general long bone proportions. It was in 2000 identified as an anurognathid, and it was confirmed that the fossil had been doctored prior to its description. A cladistic analysis by Alexander Kellner in 2003 had the same outcome, Dendrorhynchoides being found to form an anurognathid clade with Batrachognathus and Jeholopterus, that he named the Asiaticognathidae. An analysis by Lü Junchang in 2006 resolved the relations even further, finding Dendrorhynchoides to be the sister taxon of clade formed by the other two asiaticognathid species. The describers postulated a tree-dwelling lifestyle for Dendrorhynchoides as an insectivore. In 2010 a second specimen, of a juvenile, was announced, that proved that a more elongated tail was present after all, albeit not so long as the faked tail of the holotype: about 85% of femur length. This specimen eventually was designated as the holotype of Dendrorhynchoides mutoudengensis. The specimen was originally stored in the Guilin Geological Museum and designated GLGMV 0002; later it was moved to the Jinzhou Paleontological Museum and designated JZMP-04-07-3. Размеры тела в сравнении с человеком:

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Мел, авеметатарзалии, анурогнатиды, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| May 27th, 2012 | |

| 03:54 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Sordes Sordes was a small basal pterosaur from the Late Jurassic (Oxfordian - Kimmeridgian) Karabastau Svita of Kazakhstan. The genus was named in 1971 by Aleksandr Grigorevich Sharov. The type species is Sordes pilosus. The genus name means "filth" or "scum" in Latin, a reference to evil spirits in local folklore. The specific name is Latin for "hairy"; despite sordes being feminine, it has not yet been emended to pilosa. The genus is based on holotype PIN 2585/3, a crushed relatively complete skeleton on a slab. It was found in the sixties at the foothills of the Karatau in Kazakhstan. The fossil shows remains of the soft parts, such as membranes and hair. This was the first unequivocal proof that pterosaurs had a layer of fur. The integument served as insulation, an indication the group was warm-blooded, and provided a streamlined flight profile. The hairlike structures (pycnofibres) are present in two main types: longer at the extreme part of the wing membrane and shorter near the body. In the 1990s, David Unwin argued that both types were essentially not hairs but reinforcing fibres of the flight membranes. Later he emphasized that "hair" in the form of fur was indeed present on the body, after the find of new specimens clearly showing this. Sharov had already referred a paratype or second specimen: PIN 2470/1, again a fairly complete skeleton on a slab. By 2003 another six specimens had been discovered. Sordes had a 0.63 m (two feet) wingspan. The wings were relatively short. It had a slender, not round, head with moderately long, pointed jaws. The skull was about eight centimetres long. Its teeth were widely spaced, small and slanted. It had a short neck. It had a long tail, accounting for over half its length, with at the end an elongated vane. Unlike many pterosaurs, it had no head crest. Sordes had, according to Sharov and Unwin, wing membranes attached to the legs and a membrane between the legs. Sordes has been assigned to the family Rhamphorhynchidae. These were among the earliest of the pterosaurs, evolving in the late Triassic and surviving to the late Jurassic. According to Unwin, within Rhamphorhynchidae Sordes belonged to the Scaphognathinae. Other researchers however, such as Alexander Kellner and Lü Junchang, have produced cladistic analyses showing that Sordes was much more basal, and not a rhamphorhynchid. Sordes probably ate small prey, perhaps including insects and amphibians. Впервые остатки одного из них были обнаружены в 70-х годах XX века, и, судя по ним, сордесы походили на обычных птерозавров. Вместе с тем, при ближайшем рассмотрении, на этих останках выявилась одна любопытная особенность — признаки шерстяного покрова. Шерсть, вероятно, покрывала голову и большую часть туловища этих животных, кроме крыльев и хвоста, как у летучих мышей. Для многих палеонтологов столь примечательный факт послужил доказательством того, что птерозавры были теплокровными и, следовательно, вели активный образ жизни. А коли так, стало быть, шерстяной покров имелся и у других птерозавров, хотя следы его заметны далеко не на всех останках. Помимо шерстяного покрова, сордесов отличали широкие глаза и длинный узкий клюв с большими, выступающими наружу зубами. Судя по их небольшим размерам, сордесы, под стать батрахогнатам, чаще питались насекомыми, чем рыбой. Сордесы были похожи на летучих мышей: между задними лапами и основанием хвоста у них имелась кожная перепонка. Чешуйчатая щетина была у сордесов признаком, общим для всех птерозавров, тем более что ее следы проступают на их останках совершенно явно.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 03:44 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Sericipterus Sericipterus is an extinct genus of rhamphorhynchid pterosaur. It is known from the Late Jurassic (early Oxfordian age) Shishugou Formation in Xinjiang, China. The genus was named and described in 2010 by Brian Andres, James Matthew Clark and Xu Xing. The type species is Sericipterus wucaiwanensis. The generic name is derived from Latin sericum, "silk", a reference to the Silk Route, and from a Latinised Greek pteron, "wing". The specific name refers to the Wucaiwan area, itself meaning "five-colour bay" because of the many-coloured layers. The holotype specimen, IVPP V14725, consists of partly crushed, disarticulated bones that are largely preserved three-dimensionally. The wingspan has been estimated at at least 1.73 metres. The skull of Sericipterus is similar to those of the "rhamphorhynchoids" (i.e. basal pterosaurs) Angustinaripterus and Harpactognathus. It had three bony crests: a low crest on the snout, a short low parietal crest on top of the skull and a short traverse crest connected to the front edge of the latter. The parietal crest is the first reported for a non-pterodactyloid pterosaur. The same is true for the rosette, bearing two pairs of forward pointing laniaries, formed by a narrowing of the snout behind these long fangs. Another probably five pairs of teeth were present in a more posterior position in the upper jaws. The number in the lower jaw is unknown. Except for the first rather straight pair, the teeth were recurved, sharply pointed, covered with smooth enamel and circular in cross-section but equipped with two keels providing cutting edges. Sericipterus has, after a comprehensive new cladistic analysis of the Pterosauria, been placed as the sister taxon of Angustinaripterus in the Rhamphorhynchinae, a clade which also includes other large-bodied "rhamphorhynchoids", living inland as predators of small tetrapods and preserved in terrestrial sediments.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 03:18 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Scaphognathus Scaphognathus was a pterosaur that lived around Germany during the Late Jurassic. It had a wingspan of about one meter. The first known Scaphognathus specimen was described in 1831 by August Goldfuss who mistook the tailless specimen for a new Pterodactylus species: P. crassirostris. The specific name means "fat snout" in Latin. This specimen was an incomplete adult with a three foot wingspan recovered from the Solnhofen strata near Eichstätt. In 1858 Johann Wagner recognized the "rhamphorhynchoid" nature of "P." crassirostris after the discovery of the second specimen in Mühlheim, whose tail was preserved. The second Scaphognathus specimen was more complete than its predecessor, but only half the size (20 inch wingspan) and with partially ossified bones. These characters indicate that the second specimen was a juvenile. Wagner, after previous failed attempts by Leopold Fitzinger and Christoph Gottfried Andreas Giebel, who used preoccupied names, in 1861 named a distinct genus: Scaphognathus, derived from Greek skaphe, "boat" or "tub", and gnathos, "jaw", in reference to the blunt shape of the lower jaws. At present Scaphognathus is known from three specimens, all of which originated in the Kimmeridgian-age Solnhofen Limestone. Physically it was very similar to Rhamphorhynchus, albeit with notable cranial differences. For one, Scaphognathus had a proportionately shorter skull (4.5 in) with a blunter tip and a larger antorbital fenestra. Its teeth oriented vertically rather than horizontally. The traditional count of them held that eighteen teeth were in the upper jaws and ten in the lower. S. Christopher Bennett, studying a new third specimen, in 2004 determined there were only sixteen teeth in the upper jaws, the higher previous number having been caused by incorrectly adding replacement teeth. Comparisons between the scleral rings of Scaphognathus and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been diurnal. This may also indicate niche partitioning with contemporary pterosaurs inferred to be nocturnal, such as Ctenochasma and Rhamphorhynchus.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| May 23rd, 2012 | |

| 08:31 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Rhamphorhynchus Рамфоринхи (Rhamphorhynchus) — род вымерших рептилий отряда летающих ящеров (птерозавров), живших в юрском периоде (около 170—140 млн лет назад) на территории Европы (Великобритания, Испания и Германия) и Африки (Ангола и Танзания). Впервые описан палеонтологом Мейером (Meyer) в 1847 году. Включает в себя 4 вида. Все летающие ящеры (птерозавры) делятся на две группы — длиннохвостых и короткохвостых крылатых ящеров. Наиболее древние — длиннохвостые, рамфоринхи. С греческого это слово переводится как «кривоклювые», хотя, когда смотришь на реконструкцию головы рамфоринха, хочется назвать его, скорее, кривозубым. Очевидно, эти животные питались рыбой — острые длинные изогнутые зубы позволяли хорошо захватывать и удерживать скользкую добычу. Размах крыльев рамфоринха составлял 181 см. Крылья рамфоринхов были более узкими, чем у прогрессивных короткохвостых летающих ящеров. Вероятно, рамфоринхи уступали им в маневренности полета. Хвост служил рулем. The largest known specimen of Rhamphorhynchus muensteri (catalog number BMNH 37002) measures 1.26 meters (4.1 ft) long with a wingspan of 1.81 m (5.9 ft). Traditionally, the large size variation between specimens of Rhamphorhynchus has been taken to represent species variation. However, in a 1995 paper, Bennett argued that these "species" actually represent year-classes of a single species, Rhamphorhynchus muensteri, from flaplings to adults. Following from this interpretation, Bennett found several notable changes that occurred in R. muensteri as the animal aged. Juvenile Rhamphorhynchus had relatively short skulls with large eyes, and the toothless beak-like tips of the jaws were shorter in juveniles than adults, with rounded, blunt lower jaw tips eventually becoming slender and pointed as the animals grew. Adult Rhamphorhynchus also developed a strong upward "hook" at the end of the lower jaw. The number of teeth remained constant from juvenile to adult, though the teeth became relatively shorter and stockier as the animals grew, possibly to accommodate larger and more powerful prey. The pelvic and pectoral girdles fused as the animals aged, with full pectoral fusion attained by one year of age. The shape of the tail vane also changed across various age classes of Rhamphorhynchus. In juveniles, the vane was shallow relative to the tail and roughly oval, or "lancet-shaped". As growth progressed, the tail vane became diamond-shaped, and finally triangular in the largest individuals. The smallest known Rhamphorhynchus specimen has a wingspan of only 290 millimeters; however, it is likely that even such a small individual was capable of flight. Bennett examined two possibilities for hatchlings: that they were altricial, requiring some period of parental care before leaving the nest, or that they were precocial, hatching with sufficient size and ability for flight. If precocious, Bennett suggested that clutches would be small, with only one or two eggs laid per clutch, to compensate for the relatively large size of the hatchings. Bennett did not speculate on which possibility was more likely, though the discovery of a pterosaur embryo (Avgodectes) with strongly ossified bones suggests that pterosaurs in general were precocial, able to fly soon after hatching with minimal parental care. This theory was contested by a histological study of Rhamphorhynchus that showed the initial rapid growth was followed by a prolonged period of slow growth. Having determined that Rhamphorhynchus specimens fit into discrete year-classes, Bennett was able to estimate growth rate during one year by comparing the size of one-year-old specimens with two-year-old specimens. He found that the average growth rate during the first year of life for Rhamphorhynchus was 130% to 173%, slightly faster than the growth rate in alligators. Growth likely slowed considerably after sexual maturity, so it would have taken more than three years to attain maximum adult size. This growth rate is much slower than the rate seen in large pterodactyloid pterosaurs such as Pteranodon, which attained near-adult size within the first year of life. Additionally, pterodactyloids had determinate growth, meaning that the animals reached a fixed maximum adult size and stopped growing. Previous assumptions of rapid growth rate in rhamphorhynchoids were based on the assumption that they needed to be warm-blooded to sustain active flight. Warm-blooded animals, like modern birds and bats, normally show rapid growth to adult size and determinate growth. Because there is no evidence for either in Rhamphorhynchus, Bennett considered his findings consistent with an ectothermic metabolism, though he recommended more studies needed to be done. Cold-blooded Rhamphorhynchus, Bennett suggested, may have basked in the sun or worked their muscles to accumulate enough energy for bouts of flight, and cooled to ambient temperature when not active to save energy, like modern reptiles. Both Koh Ting-Pong and Peter Wellnhofer recognized two distinct groups among adult Rhamphorhynchus muensteri, differentiated by the proportions of the neck, wing, and hind limbs, but particularly in the ratio of skull to humerus length. Both researchers noted that these two groups of specimens were found in roughly a 1:1 ratio, and interpreted them as different sexes. Bennett tested for sexual dimorphism in Rhamphorhynchus by using a statistical analysis, and found that the specimens did indeed group together into small-headed and large-headed sets. However, without any known variation in the actual form of the bones or soft tissue (morphological differences), he found the case for sexual dimorphism inconclusive. In 2003, a team of researchers led by Lawrence Witmer studied the brain anatomy of several types of pterosaurs, including Rhamphorhynchus muensteri, using endocasts of the brain they retrieved by performing CAT scans of fossil skulls. Using comparisons to modern animals, they were able to estimate various physical attributes of pterosaurs, including relative head orientation during flight and coordination of the wing membrane muscles. Witmer and his team found that Rhamphorhynchus held its head parallel to the ground due to the orientation of the osseous labyrinth of the inner ear, which helps animals detect balance. In contrast, pterodactyloid pterosaurs such as Anhanguera appear to have normally held their heads at a downward angle, both in flight and while on the ground. Comparisons between the scleral rings of Rhamphorhynchus and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been nocturnal, and may have had activity patterns similar to those of modern nocturnal seabirds. This may also indicate niche partitioning with contemporary pterosaurs inferred to be diurnal, such as Scaphognathus and Pterodactylus. Several limestone slabs have been discovered in which fossils of Rhamphorhynchus are found in close association with the ganoid fish Aspidorhynchus. In one of these specimens, the jaws of an Aspidorhynchus pass through the wings of the Rhamphorhynchus specimen. The Rhamphorhynchus also has the remains of a small fish, possibly Leptolepides, in its throat. This slab, cataloged as WDC CSG 255, may represent two levels of predation; one by Rhamphorhynchus and one by Aspidorhynchus. In a 2012 description of WDC CSG 255, researchers proposed that the Rhamphorhynchus individual had just caught a Leptolepides while it was flying low over a body of water. As the Leptolepides was travelling down its pharynx, a large Aspidorhynchus would have attacked from below the water, accidentally puncturing the left wing membrane of the Rhamphorhynchus with its sharp rostrum in the process. The teeth in its snout were ensnared in the fibrous tissue of the wing membrane, and as the fish thrashed to release itself the left wing of Rhamphorhynchus was pulled backward into the distorted position seen in the fossil. The encounter resulted in the death of both individuals, most likely because the two animals sank into an anoxic layer in the water body, depriving the fish of oxygen. The two may have been preserved together as the weight of the head of Aspidorhynchus held down the much lighter body of Rhamphorhynchus. Рамфоринх, он же Rhamphorynchus, что означает примерно «клювоморд» или «кривоклювый» – один из наиболее известных птерозваров. Эти летающие ящеры обитали на, или вернее – над территорией современной Европы и Африки. Главным отличием этого вида является длинный хвост с ромбовидным окончанием.

История исследования этого вида начинается в далеком 1825 году, когда некий коллекционер, Георг, граф Мюнстерский, продемонстрировал найденные останки Самуэлю Томасу Зёммерингу. Последний счел, что скелет принадлежит некой древней ископаемой птице. Когда в процессе исследования окаменелостей были обнаружены зубы, граф отослал копию скелета Георгу Августу Гольдфуссу, который опознал в них птерозавра. Если забыть о всей путанице в наименованиях видов в науке того времени, благодаря чему рамфоринх успел побывать и Ornithocephalus Münsteri, и Ornithocephalus longicaudus, и Pterodactylus münsteri, причем, всё это за какие-то 20 лет, то в 1845 году Герман фон Мейер, который считается основателем палеонтологии позвоночных животных в Германии, присвоил виду последнее упомянутое название. В следующем году ученый пришел к выводу, что между короткохвостыми и длиннохвостыми птерозаврами различия столь существенны, что их следует выделить в отдельный подвид. Интересно также то, что те самые, первые найденные, останки были утеряны во время второй мировой. Обычно в таких случаях новые найденные останки (или неотип) обозначаются как тип, но в данном случае от этого отказались, так как существовало большое количество хорошо сохранившихся дубликатов оригинала. У молодого рамфоринха был относительно короткий череп с большими глазами. Челюсти имели тупую закругленную кромку. По мере роста животного кромки становились более тонкими и вытянутыми. У взрослых особей также был мощный крюк на нижней челюсти, направленный вверх. Количество зубов с возрастом не менялось; зубы становились более короткими и похожими на пеньки. Вероятно, это помогало ловить более крупную и сильную добычу. В возрасте года происходило объединение грудной клетки с тазовым поясом. Форма хвостовых лопастей также менялась. У юных, «неоперившихся» особей хвостовая лопатка была маленькой, узкой, овальной формы. По мере роста она прогрессировала, хвостовые отростки становились ромбовидными, и, наконец, треугольными у крупных особей. Самая маленькая из известных науке особей имела размах крыльев всего 29 сантиметров, однако ученые предполагают, что даже столь небольшие экземпляры были способны на полет. Ученые рассматривали две гипотезы: первая – птенцы с самого рождения обладали размерами и силой, достаточными для полета и вторая – молодым рамфоринхам требовался некоторый период ухода и обучения со стороны родителей. Пока не был исследован эмбрион, содержащий окаменевшие костные останки, не было возможности предположить, какая из гипотез была более правдоподобна, но последние исследования показали, что рамфоринхи были скорее всего выводковыми животными и птенцы уже вскоре после рождения обладали способностью к полёту. Позвоночник рамфоринхов состоял из 8 шейных, 10—15 спинных, 4— 10 крестцовых и 10—40 хвостовых позвонков. Грудная клетка была широкой и имела высокий киль. Лопатки были длинными, тазовые кости срослись. Рамфоринхи имели длинные хвосты, длинные узкие крылья и большой череп с многочисленными зубами. Длинные зубы разной величины выгибались вперед. Хвост ящера заканчивался лопастью, служившей рулем. Рамфоринхи имели легкие трубкообразные кости. Первый палец имел вид маленькой кости либо совсем отсутствовал. Второй, третий и четвертый пальцы состояли из двух, реже трех костей и имели когти. Задние конечности были довольно сильно развиты. На их концах имелись острые когти. Чрезвычайно удлиненный внешний пятый палец передних конечностей состоял из четырех суставов. Рамфоринхи были мелкими птерозаврами, они могли взлетать с земли. Рамфоринхи селились по берегам водоемов большими колониями. Они питались в основном рыбой. Их клюв полный зубов был идеально приспособлен для захвата скользкой рыбы. Рамфоринхи выработали уникальный способ рыбной ловли, при котором мембраны их крыльев оставались сухими: пролетая над водой, рамфоринхи раскрывали клюв и опускали его под воду. Таким образом, они захватывали все, что попадется и что они могли проглотить. Кроме рыбы, рамфоринх мог питаться личинками насекомых, которые жили под корой деревьев. Также рамфоринхи питались яйцами других животных, которые откладывали их в песок на берегу. Летающие ящеры жили только в мезозойскую эру, причем их расцвет приходится на позднеюрский период. Их предками являлись, по-видимому, вымершие древние пресмыкающиеся псевдозухии. Длиннохвостые формы появились раньше короткохвостых. В конце юрского периода длиннохвостые птерозавры вымерли. Следует заметить, что рамфоринхи и другие летающие ящеры не были предками птиц и летучих мышей. Летающие ящеры, птицы и летучие мыши произошли и развивались своим собственным, уникальным путём, и между ними отсутствуют близкие родственные связи. Единственный общий признак для них — умение летать. И хотя все они приобрели эту способность благодаря изменению передних конечностей, отличия в строении их крыльев убеждают нас в том, что у них были совершенно разные предки.

Репродукции (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8):

( Далее ) Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8):

( Далее ) Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| May 22nd, 2012 | |

| 08:11 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Nesodactylus Nesodactylus was a genus of "rhamphorhynchoid" pterosaur from the Oxfordian-age Upper Jurassic Jagua Formation of Pinar del Río, western Cuba. Its remains were collected but not prepared by Barnum Brown in 1918, from rocks better known for their fossils of marine life. When seven black chalkstone blocks were prepared from 1966 by Richard Lund by dissolving the substrate in acid, this revealed the remains of a pterosaur. Ned Colbert described and named the genus in 1969. The type species is Nesodactylus hesperius. The genus name is derived from Greek nesos, "island" and daktylos, "finger", a reference to the island of Cuba and the typical wing finger of pterosaurs. The specific name means "western", from Greek hesperios. The genus is based on holotype AMNH 2000, a partial skeleton including a skull fragment, numerous vertebrae from all parts of the spine and tail, zygapophyses (interpreted by Colbert as ossified tendons) on the tail, the pectoral girdle and a very deeply keeled sternum, arms and partial hands, part of the pelvis, parts of both femorae, partial metatarsals, and ribs. The specimen was disarticulated but associated and not very compressed; during the preparation from the limestone with acid, the bones were not completely removed. Colbert found Nesodactylus to have had longer wings and more robust limbs and longer legs than related Rhamphorhynchus, although of a similar size and overall anatomy. He classified it as a rhamphorhynchid and more precisely as a member of the Rhamphorhynchinae. In 1977 James A. Jensen and John Ostrom by mistake referred to it as Nesodon (1977). Although there is little overlapping material with contemporaneous Cacibupteryx, the two are clearly different based on details of the elbow and quadrate. At least one recent review suggests it was a rhamphorhynchine, while another does not classify it.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 07:39 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

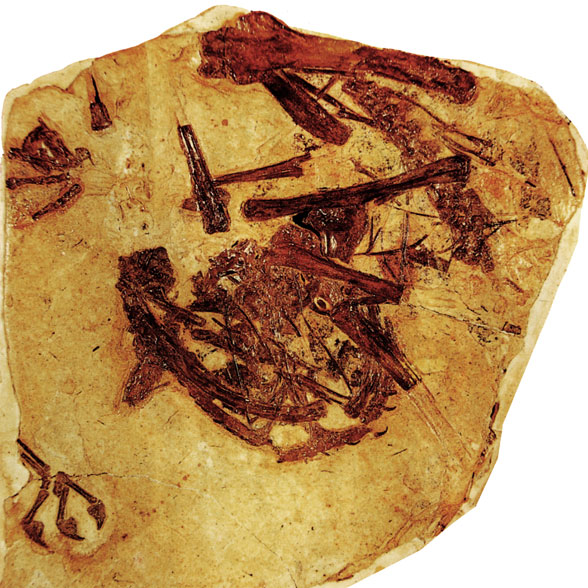

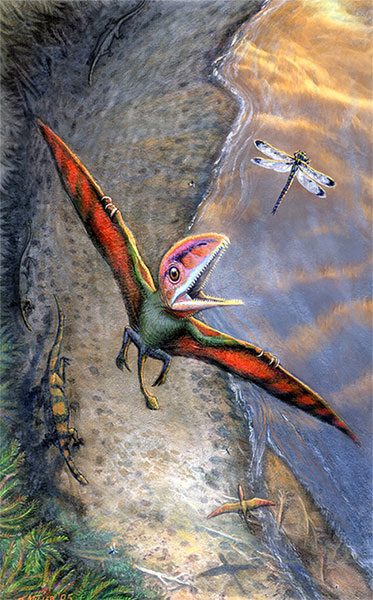

Jeholopterus Jeholopterus was a small anurognathid pterosaur from the Daohugou Beds of northeastern China (of uncertain age, probably Middle or Late Jurassic), between 168 and 152 million years ago), preserved with hair and skin remains. The type species is based on holotype IVPP V12705, a nearly complete specimen from the Daohugou beds of Ningcheng County in the Neimongol (Inner Mongolia) Autonomous Region of China. The specimen is crushed into a slab and counterslab pair, so that parts of the specimen are preserved on one side of a split stone and some on the other. This includes exquisite preservation of carbonized skin fibers and, arguably, "hair" or "protofeathers." The fibers are preserved around the body of the specimen in a "halo." Wing tissue is preserved, though its extent is debatable, including the exact points of attachment to the legs (or if it attached to the legs at all). In 2009 Alexander Kellner published a study reporting the presence of three layers of fibres in the wing, allowing the animal to precisely adapt the wing profile. As an anurognathid, Jeholopterus shows the skull form typical for this group, being wider than it was long (28 mm), with a very broad mouth. Most teeth are small and peg-like, but some are longer and recurved. The neck was short with seven or eight cervical vertebrae. Twelve or thirteen dorsal vertebrae are present and three sacrals. There are five pairs of belly ribs. The tail vertebrae have not been preserved. The describers argue that Jeholopterus had a short tail, a feature seen in other anurognathids but unusual for "rhamphorhynchoid" (i.e. basal) pterosaurs that typically have a long tail. Wang et al. cited the presence of a fringe of hair in the region of the tail to infer the presence of a short tail. However, a subsequent study by Dalla Vecchia argued that gleaning any information about the tail is impossible, given that the tail is "totally absent" in the fossil. The wing bones are robust. The metacarpals are very short. A short pteroid, supporting a propatagium, is pointing towards the body. The hand claws are long and curved. The wings of Jeholopterus show evidence that they attached to the ankle, according to Wang et al.. They are relatively elongated with a wingspan of ninety centimetres. The legs are short but robust. The toes bear well-developed curved claws, but these are not as long as the hand claws. The fifth toe is elongated, according to the authors supporting a membrane between the legs, the uropatagium. Jeholopterus was by the authors assigned to the Anurognathidae. In 2003 a cladistic analysis by Kellner found it to be a member, together with Dendrorhynchoides and Batrachognathus of an anurognathid clade Asiaticognathidae. An analysis by Lü Junchang in 2006 resolved its position as being the sister taxon of Batrachognathus. Далее идёт пятиминутка острого, запущенного хумора: Though he never examined the fossil himself, advertising artist David Peters has popularized his idiosyncratic opinions about Jeholopterus and other pterosaurs widely on the internet. In general he finds and illustrates hosts of ornamental features and even multiple embryos although no other researchers have ever confirmed his findings. By manipulating downloaded images of Jeholopterus in the computer art program Photoshop, David Peters (2003) reported that he discovered an unusual suite of soft-tissue remains, including a horse-like tail Peters speculated may have been used as a fly sweeper/distractor, as well as a long fly lure (similar to that of the anglerfish) protruding from the head, and a fin or series of fins along the back. Peters also reported that he had found "rattlesnake-like fangs", and these, along with what he described as a rattle-snake-like mandible, buttressed palate, "surgically-sharp" unguals, robust limbs and other characters suggested that Jeholopterus was a vampire pterosaur adapted to plunging fangs into tough hide, then rotating the skull forward locking the fangs beneath the hide to improve adhesion. The small teeth of the lower jaw would not have penetrated but squeezed the wound like a pliers. Prominent pterosaur researcher Chris Bennett has described Peters' findings as "fantasy" and has vehemently denounced his methodology.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, анурогнатиды, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| May 17th, 2012 | |

| 07:46 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Dorygnathus Dorygnathus ("spear jaw") was a genus of pterosaur that lived in Europe during the Early Jurassic period, 180 million years ago when shallow seas flooded much of the continent. It had a short 1.5 meter (five feet) wingspan, and a relatively small triangular sternum, which is where its flight muscles attached. Its skull was long and its eye sockets were the largest opening therein. Large curved fangs that "intermeshed" when the jaws closed featured prominently at the front of the snout while smaller, straighter teeth lined the back. Having variable teeth, a condition called heterodonty, is rare in modern reptiles but more common in primitive pterosaurs. The heterodont dentition in Dorygnathus is consistent with a piscivorous (fish-eating) diet. The fifth digit on the hindlimbs of Dorygnathus was unusually long and oriented to the side. Its function is not certain, but the toe may have supported a membrane like those supported by its wing-fingers and pteroids. Dorygnathus was according to David Unwin related to the Late Jurassic pterosaur, Rhamphorhynchus and was a contemporary of Campylognathoides in Holzmaden and Ohmden. Dorygnathus in general has the build of a basal, i.e. non-pterodactyloid pterosaur: a short neck, a long tail and short metacarpals — although for a basal pterosaur the neck and metacarpals of Dorygnathus are again relatively long. The skull is elongated and pointed. The largest known cranium, that of specimen MBR 1920.16 prepared by Bernard Hauff in 1915 and eventually acquired by the Humboldt Museum in Berlin, has a length of sixteen centimetres. In the skull the eye socket forms the largest opening, larger than the fenestra antorbitalis that is clearly separated from the slit-like bony naris. No bony crest is visible on the rather straight top of the skull or snout. The lower jaws are thin at the back but deeper toward the front where they fuse into the symphysis ending in a toothless point after which the genus has been named. In MBR 1920.16, the mandibula as a whole has a length of 147 millimetres. In the lower jaws the first three pairs of teeth are very long, sharp and pointing outwards and forwards. They contrast with a row of eight or more upright-standing much smaller teeth that gradually diminish in size towards the back of the lower jaw. No such extreme contrast exists in the upper jaws, but the four teeth in the premaxilla are longer than the seven in the maxilla that again become smaller posteriorly. The total number of teeth is thus at least 44. The long upper and lower front teeth interlaced when the beak was closed; due to their extreme length they then projected considerably beyond the upper and lower margins of the head. According to Padian, eight cervical, fourteen dorsal, three or four sacral and twenty-seven or twenty-eight caudal vertebrae are present. The exceptional fourth sacral is the first of the normal caudal series. The number of caudals is not certain because their limits are obscured by long thread-like extensions, stiffening the tail. The cervical vertebrae are rather long and strongly built, their upper surface having a roughly square cross-section. They carry double-headed thin cervical ribs. The dorsal vertebrae are more rounded with flat spines; the first three or four carry ribs that contact the sternal ribs; the more posterior ribs contact the gastralia. The first five or six, rather short, caudal vertebrae form a flexible tail base. To the back the caudals grow longer and are immobilised by their intertwining extensions with a length of up to five vertebrae which together surround the caudals with a bony network, allowing the tail to function as a rudder. The breastbone is triangular and relatively small; Padian has suggested it may have been extended at its back with a cartilaginous tissue. It is connected to the coracoid which in older individuals is fused to the longer scapula forming a saddle-shaped shoulder joint. The humerus has a triangular deltopectoral crest and is pneumatised. The lower arm is 60% longer than the upper arm. From the five carpal bones in the wrist a short but robust pteroid points towards the neck, in the living animal a support for a flight membrane, the propatagium. The first three metacarpals are connected to three small fingers, equipped with short but strongly curved claws; the fourth to the wing finger, in which the second or third phalanx is the longest; the first or fourth the shortest. The wing finger supports the main flight membrane. In the pelvis, the ilium, ischium and pubis are fused. The ilium is elongated with a length of six vertebrae. The lower leg, in which the lower two thirds of the tibia and fibula of adult specimens are fused, is a third shorter than the thighbone, the head of which makes an angle of 45° with its shaft. The proximal tarsals are never fused in a separate astragalocalcaneum; a tibiotarsus is formed. The third metatarsal is the longest; the fifth is connected to a toe of which the second phalanx shows a 45° bend and has a blunt and broad end; it perhaps supported a membrane between the legs, a cruropatagium. In some specimens, soft parts have been preserved but these are rare and limited, providing little information. It is unknown whether the tail featured a vane on its end, as with Rhamphorhynchus. However, Ferdinand Broili reported the presence of hairs in specimen BSP 1938 I 49, an indication that Dorygnathus also had fur and an elevated metabolism, as is presently assumed for all pterosaurs. In 1971 Rupert Wild described and named a second species: Dorygnathus mistelgauensis, based on a specimen collected in a brick pit near the railway station of Mistelgau, to which the specific name refers, by teacher H. Herppich, who donated it to the private collection of Günther Eicken, a local amateur paleontologist at Bayreuth, where it still resides. As a result the exemplar has no official inventory number. The fossil comprises a shoulder-blade with wing, a partial leg, a rib and a caudal vertebra. Wild justified the creation of a new species name by referring to the great size, with an about 50% larger wingspan than with a typical specimen; the short lower leg and the long wing. Padian in 2008 pointed out that D. banthensis specimen MBR 1977.21, the largest then known, has with a wingspan of 169 centimetres an even larger size; that wing and lower leg proportions are rather variable in D. banthensis and that the geological age is comparable. He concluded that D. mistelgauensis is a subjective junior synonym of D. banthensis. Dorygnathus is commonly thought to have had a piscivorous way of living, catching fish or other slippery sea-creatures with its long teeth. This is confirmed by the fact that the fossils have been found in marine sediments, deposited in the seas of the European Archipelago. In these it is present together with the pterosaur Campylognathoides that however is much more rare. Very young juveniles of Dorygnathus are unknown, the smallest discovered specimen having a wingspan of sixty centimetres; perhaps they were unable to venture far over open sea. Padian concluded that Dorygnathus after a relatively fast growth in its early years, faster than any modern reptile of the same size, kept slowly growing after having reached sexual maturity, which would have resulted in exceptionally large individuals with a 1.7 metres wingspan. On land, Dorygnathus was probably not a good climber; its claws show no special adaptations for this type of locomotion. According to Padian, Dorygnathus, as a small pterosaur with a long tail, was well capable of bipedal movement, though its long metacarpals would make him better suited for a quadrupedal walk than most basal pterosaurs. Most researchers however, today assume quadrupedality for all pterosaurs.

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4):

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 06:23 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Dimorphodon Диморфодон (двуформозуб) — вымершее летающее пресмыкающееся, жившее от 200 до 180 миллионов лет назад. Размах крыльев до 2 м, длина от кончика головы до кончика хвоста — 120 см, размер головы — до 30 см. Диморфодон – один из древнейших летающих динозавров (птерозавров), обитавший в юрском периоде. Этот ящер имел мощные крылья, размах которых составлял около 2 метров. Длина его тела с учётом хвоста составляла 1,2 метра, а размер головы около 30 сантиметров. Вытянутая передняя часть головы напоминала клюв, но, в отличие от аналогичной части тела современных птиц, он был усажен огромным количеством острых, загнутых назад зубов. Как на задних конечностях, так и на концах крыльев располагались острые когти. Всё это говорит о том, что диморфодон был хищником, но, судя по небольшим размерам, питался он в основном рыбой и насекомыми. Вероятно, диморфодоны могли не только летать, но и лазать по деревьям и даже несколько неуклюже передвигаться по суше, используя при этом все 4 конечности. Вид этот изучен довольно слабо, так как на данный момент были найдены останки лишь одного экземпляра на территории Англии. Вполне возможно, что диморфодоны обитали не только в Европе. Dimorphodon had a large, bulky skull approximately 22 centimetres in length, whose weight was reduced by large openings separated from each other by thin bony partitions. Its structure, reminiscent of the supporting arches of a bridge, prompted Richard Owen to declare that, in far as achieving great strength from light-weight materials was concerned, no vertebra was more economically constructed; Owen saw the vertebrate skull as a combination of four vertebrae modified from the ideal type of the vertebra. The front of the upper jaw had four or five fang-like teeth followed by an indeterminate number of smaller teeth; the maxilla of all exemplars is damaged at the back. The lower jaw had five longer teeth and thirty to forty tiny, flattened pointed teeth, shaped like a lancet. Many depictions give it a speculative puffin-like 'beak' because of similarities between the two animals' skulls. The body structure of Dimorphodon displays many "primitive" characters, such as, according to Owen, a very small brain-pan and proportionally short wings. The first phalanx in its flight finger is only slightly longer than its lower arm. The neck was short but strong and flexible and may have had a membraneous pouch on the underside. The vertebrae had pneumatic foramina, openings through which the air sacks could reach the hollow interior. Dimorphodon had an adult body length of 1 metre (3.3 ft) long, with a 1.45 meter (4.6 ft) wingspan. The tail of Dimorphodon was long and consisted of thirty vertebrae. The first five or six were short and flexible but the remainder gradually increased in length and were stiffened by elongated vertebral processes. The terminal end of the tail may have borne a Rhamphorhynchus-like tail vane, although no soft tissues have yet been found of Dimorphodon to confirm this speculation Owen saw Dimorphodon as a quadruped. He speculated that the fifth toe supported a membrane between the tail and the legs and that the animal was therefore very ungainly on the ground. His rival Harry Govier Seeley however, propagating the view that pterosaurs were warm-blooded and active, argued that Dimorphodon was either an agile quadruped or even a running biped due to its relatively well developed hindlimbs and characteristics of its pelvis. This hypothesis was revived by Kevin Padian in the nineteen eighties. However, fossilised track remains of other pterosaurs (ichnites) show a quadrupedal gait while on the ground and these traces are all attributed to derived pterosaurs with a short fifth toe. Dimorphodon's was elongated, clawless, and oriented to the side. David Unwin has therefore argued that even Dimorphodon was a quadruped, a view confirmed by computer modelling by Sarah Sangster. Our knowledge of how Dimorphodon lived is limited. It perhaps mainly inhabited coastal regions and might have had a very varied diet. Buckland suggested it ate insects. Later it became common to depict it as a piscivore (fish eater), though Buckland's original idea is more well supported by biomechanical studies. Dimorphodon had an advanced jaw musculature specialized for a "snap and hold" method of feeding. The jaw could close extremely quickly but with relatively little force or tooth penetration. This, along with the short and high skull and longer, pointed front teeth suggest Dimorphodon was an insectivore, though it may have occasionally eaten small vertebrates and carrion as well. In 1870 Seeley assigned Dimorphodon its own family, the Dimorphodontidae, with Dimorphodon as the only member. It was suggested in 1991 by German paleontologist Peter Wellnhofer that Dimorphodon might be descended from the earlier European pterosaur Peteinosaurus. Later exact cladistic analyses are not in agreement. According to Unwin, Dimorphodon was related to, though probably not a descendant of, Peteinosaurus, both forming the clade Dimorphodontidae, the most basal group of the Macronychoptera and within it the sister group of the Caelidracones. This would mean that both dimorphodontid species would be the most basal pterosaurs known with the exception of Preondactylus. According to Alexander Kellner however, Dimorphodon is far less basal and not a close relative of Peteinosaurus.

Репродукции (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15):

( Далее ) Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6):

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, диморфодонтиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| May 9th, 2012 | |

| 04:12 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Campylognathoides Campylognathoides ("curved jaw", Strand 1928) was a genus of "rhamphorhynchoid" pterosaur, discovered in the Württemberg Lias deposits, the first specimen consisting of wing fragments. Further better preserved specimens were found in the Holzmaden shale and it was based on these specimens that Felix Plieninger erected a new genus. Compared to its contemporary from the same layers Dorygnathus, the snout on this genus is relatively short, though the skull is still in general elongated, be it much lighter built. The large eye sockets, placed low in the skull above a narrow jugal, have caused some researchers to speculate that Campylognathoides had especially acute vision, or possibly even a nocturnal lifestyle. The back of the skull is relatively high and flat, with a sudden downturn just in front of the eyes. The snout ends in a slender point curving a bit upwards at its very end. A large part of the snout is occupied by long bony nares. Below them a small triangular skull opening, the fenestra antorbitalis is present. Reflecting the more shallow snout, the teeth of Campylognathoides are also short and not at all laniaries or fang-like as in the markedly heterodont Dorygnathus. They are conical and recurved but have a broad base with the point bevelled off from the inside forming a sharp and strong cutting surface. In the upper jaw there are four rather widely spaced teeth in the praemaxilla gradually increasing in size from the front to the back; the fourth pair of teeth is the largest. Behind them are ten smaller teeth in the maxilla, gradually decreasing posteriorely. In the lower jaw there are twelve to fourteen teeth present in C. liasicus, sixteen to nineteen in C. zitteli. The largest total number is thus 66. According to a study by Kevin Padian there are eight cervical vertebrae, fourteen dorsals, four or five sacrals and up to 38 caudal vertebrae. The tail base is flexible with about six short vertebrae; behind them the caudals elongate and are stiffened by very long extensions allowing the tail to function as a rudder. The sternum of Campylognathoides was a rather large rectangular plate of bone with a short forward-facing crest called a cristospina. The upper arm is short but robust with a square deltopectoral crest. The lower arm too is short but wing length is considerable due to the hand, which has short metacarpals but a very long wing finger for a basal pterosaur, of which the second phalanx is the largest. The pteroid is short and robust. The pelvis is not very well known. A fossil collector found a well preserved Campylognathoides hip in a Braunschweig shale quarry in 1986. This pelvis, BSP 1985 I 87, proved to be scientifically significant because the hip socket was according to Peter Wellnhofer in an upward lateral position, preventing the animal from being able to orient its legs erectly like in dinosaurs, birds and mammals. This would prove that Campylognathoides was not well able to walk on its hind legs but must have walked quadrupedally. This gait posture has been confirmed in other "rhamphorhynchoids" (i.e. basal pterosaurs) as well. However, Padian in 2009 concluded the opposite, stating that an erected position was necessary to place the feet on the ground and that, though a quadrupedal gait was possible, a bipedal way of locomotion was a precondition for a fast gait. This subject remains highly controversial. The leg is rather short and the feet are small. The fifth toe, often interpreted as carrying a membrane between the legs, is exceptionally short for a basal pterosaur. Plieninger in his later publications assigned Campylognathus to the "Rhamphorhynchoidea". As this suborder is a paraphyletic assemblage of not specially related basal pterosaurs, this classification merely states the negative fact that it was not a pterodactyloid. A positive determination was first attempted by Baron Franz Nopcsa who in 1928 assigned the genus to the subfamily Rhamphorhynchinae within the family Rhamphorhynchidae. After a period in which very little work was done on pterosaur systematics, in 1967 Oskar Kuhn placed Campylognathoides in its own subfamily within the Rhamphorhynchidae, the Campylognathoidinae. However, in 1974 Peter Wellnhofer concluded that it was placed in a more basal position in the phylogenetic tree, below the Rhamphorhynchidae. In the early twenty-first century this was confirmed by the first extensive exact cladistic analyses. In 2003 both David Unwin and Alexander Kellner introduced a clade Campylognathoididae; within Unwin's terminology this clade is the sister clade of the Breviquartossa within the Lonchognatha; applying Kellner's terminology it is the most basal off-shoot within the Novialoidea. There is no material difference between the two positions. According to the analyses Campylognathoides would be closely related to Eudimorphodon, to which it is similar in skull, sternum and humerus form. This was confirmed by Padian in 2009, though Padian also pointed out several basal features present in Eudimorphodon but lacking in Campylognathoides. In 2010 an analysis was published by Brian Andres showing that Eudimorphodon together with Austriadactylus formed a very basal clade, leaving Campylognathoides as the only known member of the Campylognathoididae. Traditionally a piscivore lifestyle is attributed to Campylognathoides, as to most pterosaurs; in this case supported by the provenance of the finds from marine sediments and the very long wings. Padian however, has suggested that, in view of the stout short teeth, ideal for delivering a piercing bite, the form might well have been a predator of small terrestrial animals instead. The niche of specialised fish eater would then have been filled by Dorygnathus which is five times as common in the layers. The area of the fossil sites was in the early Jurassic located to the northwest of a large island , the Massif of Bohemia, situated in a shallow gulf of the Tethys Sea.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 04:01 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Batrachognathus Batrachognathus is an extinct genus of "rhamphorhynchoid" pterosaur from the Late Jurassic (Oxfordian - Kimmeridgian) Karabastau Svita of the central Asian republic of Kazakhstan. The genus was named in 1948 by the Russian paleontologist Anatoly Nicolaevich Ryabinin. The type species is Batrachognathus volans. The genus name is derived from Greek batrakhos, "frog" and gnathos, "jaw", in reference to the short wide head. The specific epithet means "flying" in Latin. Three fossils have been found in a lacustrine sediment in the North-West Tien Shan foothills of the Karatau Mountains. In the Jurassic this area had some similarities in habitat to the Solnhofen lagoon deposits in Bavaria, Germany. The genus is based on holotype PIN 52-2, an incomplete and disarticulated skeleton consisting of skull fragments, jaws, vertebrae, ribs, legs and wing bones. The skull of 48 mm long is high, short and broad. The upper jaws have in total 22 or 24 recurved conical teeth; with the lower jaws they make a short and very wide mouth. The animal is not preserved with a tail. Whether it had one is debatable; usually it is assumed a short tail was present. The wingspan has been estimated at 50 cm; David Unwin in 2000 gave a higher estimate of 75 cm. Batrachognathus was assigned to the Anurognathidae, as a relative of Anurognathus. In 2003 it was joined with the Asian anurognathids Dendrorhynchoides and Jeholopterus in a clade Asiaticognathidae by Alexander Kellner. According to an analysis in 2006 by Lü Junchang Batrachognathus and Jeholopterus were sister taxa. Like all anurognathids Batrachognathus is assumed to have been an insectivore, catching insects on the wing with its broad mouth.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, анурогнатиды, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 03:23 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Anurognathus Анурогнат (Anurognathus от греч. αν — без, греч. оυρα — хвост и греч. γναθος — челюсти) — род малых птерозавров семейства Anurognathidae, представители которого жили около 150 миллионов лет назад в конце юрского периода. Род был описан и назван Людвигом Дёдерляйном (Ludwig Döderlein) в 1923 году. Типовым видом является Anurognathus ammoni. Представители рода отличаются необычной внешностью по отношению к другим птерозаврам подотряда Рамфоринхоиды. Видовое название ammoni дано в честь баварского геолога Людвига фон Аммона, который собрал коллекцию ископаемых, в которой был и Anurognathus ammoni. Анурогнат означает буквально «бесхвостый» или «беззубый» — что ж, вполне понятная, хотя и не совсем точная характеристика применительно к этим необычным птерозаврам. Судить об анурогнатах ученым остаётся только по останкам одной-единственной особи, обнаруженной в Германии в 20-е годы XX века. Хвост у него и правда походил на обрубок, голова была маленькая и тупорылая, а в пасти имелось всего несколько мелких зубов. Зато анурогнаты обладали хорошо развитыми конечностями. Впрочем, наличие таких признаков объясняется тем, что найденные останки принадлежали молодой особи, — у взрослого животного они наверняка были бы другими. Кроме того, анурогнаты, возможно, принадлежали к легким охотникам, и добычей им служили стрекозы и прочие насекомые, которых они отлавливали, прыгая со спин динозавров, используя их как живые трамплины. В размахе крыльев достигали 50 см. Anurognathus had a short head with pin-like teeth for catching insects and although it traditionally is ascribed to the long-tailed pterosaur group "Rhamphorhynchoidea", its tail was comparatively short, allowing it more maneuverability for hunting. According to Döderlein the reduced tail of Anurognathus was similar to the pygostyle of modern birds. Its more typical "rhamphorhynchoid" characters include its elongated fifth toe and short metacarpals and neck. With an estimated wingspan of fifty centimetres (20 inches) and a nine centimetre long body (skull included), its weight was limited: in 2008 Mark Paul Witton estimated a mass of forty grammes for a specimen with a 35 centimetre wingspan. The holotype was redescribed by Peter Wellnhofer in 1975. Later a second, smaller, specimen was found, probably of a subadult individual. Its slab and counterslab are separated and both were sold to private collections; neither has an official registration. It was described by S. Christopher Bennet in 2007. This second exemplar is much more complete and better articulated. It shows impressions of a large part of the flight membrane and under UV-light remains of the muscles of the thigh and arm become visible. It provided new information on many points of the anatomy. The skull was shown to have been very short and broad, wider than long. It transpired that Wellnhofer had incorrectly reconstructed the skull in 1975, mistaking the large eye sockets for the fenestrae antorbitales, skull openings that in most pterosaurs are larger than the orbits but in Anurognathus are small and together with the nostrils placed at the front of the flat snout. The eyes pointed forwards to a degree, providing some binocular vision. Most of the skull consisted of bone struts. The presumed pygostyle was absent; investigating the real nine tail vertebrae instead of impressions showed that they were unfused, though very reduced. The wing finger lacked the fourth phalanx. According to Bennett a membrane, visible near the shin, showed that the wing contacted the ankle and was thus rather short and broad. Bennett also restudied the holotype, interpreting bumps on the jaws as an indication that hairs forming a protruding bristle were present on the snout. The Anurognathidae were a group of small pterosaurs, with short tails or tailless, that lived in Europe and Asia during the Jurassic and early Cretaceous periods. Four genera are known: Anurognathus, from the Late Jurassic of Germany, Jeholopterus, from the Middle or Late Jurassic of China, Dendrorhynchoides, from the Early Cretaceous of China, and Batrachognathus, from the Late Jurassic of Kazakhstan. Bennett (2007) claimed that the holotype of Mesadactylus, BYU 2024, a synsacrum, belonged to an Anurognathid. Mesadactylus is from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the USA. Indeterminate Anurognathid remains have also been reported from the Middle Jurassic Bakhar Svita of Mongolia. A family Anurognathidae was named in 1928 by Franz Nopcsa von Felső-Szilvás (as the subfamily Anurognathinae) with Anurognathus as the type genus. The family name Anurognathidae was first used by Oskar Kuhn in 1967. Both Alexander Kellner and David Unwin in 2003 defined the group as a node clade: the last common ancestor of Anurognathus and Batrachognathus and all its descendants. The phylogeny of the Anurognathidae is uncertain. Some analyses, as those of Kellner, place them very basal in the pterosaur tree. However, they do have some characteristics in common with the derived Pterodactyloidea, such as the short and fused tail bones. In 2010 an analysis by Brian Andres indicated the Anurognathidae and the Pterodactyloidea were sister taxa. This conforms better to the fossil record because no early anurognathids are known and would require a ghost lineage of over sixty million years.

Репродукции (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10):

( Далее )

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, анурогнатиды, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 03:07 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Angustinaripterus Angustinaripterus was a basal pterosaur, belonging to the Breviquartossa, and discovered at Dashanpu near Zigong in the Szechuan province of China. Angustinaripterus was named in 1983 by He Xinlu. The type species is Angustinaripterus longicephalus. The genus name is derived from Latin angustus, "narrow" and naris, "nostril", combined with Latinized Greek pteron, "wing". The specific name is derived from Latin longus, "long", and Greek kephale, "head". The holotype, ZDM T8001, is a single skull with lower jaws, found in 1981 by researchers from the Zigong Historical Museum of the Salt Industry, in the Xiaximiao Formation (Bathonian). The skull, of which the left side is severely damaged, is very elongated and flat. The back part is missing; in its conserved state it has a length of 192 millimetres; the total length in a complete state was estimated at 201 millimetres. On its top is a low crest, two to three millimetres high. The nares are long, slit-like and positioned above and in front of the large skull openings, the fenestrae antorbitales, with which they are not confluent. Of the jaws, which are very straight, the front part is lacking. There are six pairs of teeth in the maxillae and three pairs in the praemaxillae. In the mandible there are at least ten pairs of teeth, perhaps twelve. The back teeth are small, the front teeth are very long, robust and curved, pointing moderately forwards. At the front they form a large, intermeshing "prey grab", that may have been used to snatch fish from the water surface. The teeth of Angustinaripterus resemble those of Dorygnathus. He placed Angustinaripterus into the Rhamphorhynchidae. Because of the derived morphology and the large geographical distance with comparable European forms He also created a special subfamily Angustinaripterinae, of which Angustinaripterus itself is the only known member; because of this redundancy the concept is rarely used. He concluded that Angustinaripterus was directly related to the Scaphognathinae. David Unwin however, considers it a member of the other rhamphorhynchid subgroup: the Rhamphorhynchinae. Peter Wellnhofer in 1991, assuming the skull length was 16.5 centimetres, estimated the wingspan at 1.6 metres.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхиды, рамфоринхоидеи |

| March 10th, 2012 | |

| 12:42 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Preondactylus Preondactylus is a genus of long-tailed pterosaur from the Late Triassic that inhabited what is now Italy. It was discovered by Nando Buffarini in 1982 near Udine in the Preone valley of the Italian Alps. Preondactylus had single cusp teeth, meaning they had one point on each tooth. Its diet either consisted of fish, insects or both, but there is still debate going on as the tooth structure could indicate either diet (or both). It had short wings, whose total span was only 45 cm (18 in), and relatively long legs. The short wings were a "primitive" feature for pterosaurs, but Preondactylus was a fully developed flier. When Buffarini first discovered Preondactylus, the thin slab of bituminous, dolomitic limestone containing the fossil was accidentally broken into pieces while being extracted. After reassembly the rock was cleaned with water by him and his wife and the marl and in it the bone was washed away and lost. All that was left was a negative imprint on the stone, of which a silicon rubber cast was made to allow for subsequent study of the otherwise lost remains. Most of the skeleton is known, but the posterior portions of the skull have not been preserved. This first specimen is the holotype: MFSN-1891. A second, disarticulated specimen, MFSN-1770, was found at the same locale in 1984 about 150-200 meters deeper into the strata than the original find. The second specimen appears to have been preserved in the gastric pellet of a predatory fish, which had consumed the pterosaur and vomited up the indigestible pieces that would later fossilize. More detailed knowledge of the variability of Triassic pterosaurs has made the identification of this specimen as Preondactylus uncertain. A third specimen is MFSN 25161, a partial skull, lacking the lower jaws. The species was described and named by Rupert Wild in 1984. The genus name refers to Preone, the specific name honours Buffarini. Rupert classified the new species within Rhamphorhynchidae, of which group very old species are known such as Dorygnathus, but soon it was understood the form was much more basal. A cladistic analysis by David Unwin found Preondactylus as the most basal pterosaur, and the species was accordingly used by him for a node clade definition of the clade Pterosauria. Other analyses however, have found a somewhat more derived position for Preondactylus.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Триас, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 12:23 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Peteinosaurus Peteinosaurus (pronounced /pɛˌtaɪnəˈsɔrəs/ or /pɛˌtinəˈsɔrəs/) was a prehistoric reptile genus belonging to the Pterosauria. It lived in the late Triassic period in the middle Norian (about 221-210 million years ago). Three fossils have been found near Cene, Italy. The first fossil, the holotype MCSNB 2886, is fragmentary and disarticulated. The second, the articulated paratype MCSNB 3359, lacks any diagnostic features of Peteinosaurus and thus might be a different species. This paratype has a long tail (20 cm) made more stiff by long extensions of the vertebrae; this feature is common among pterosaurs of the Triassic. The third exemplar is MCSNB 3496, another fragmentary skeleton. All specimina are those of subadults and of none has the skull been preserved. Like most pterosaurs, Peteinosaurus had bones that were strong but very light. Peteinosaurus is trimorphodontic, with three types of conical teeth. An insectivorous lifestyle has been attributed to Peteinosaurus. The fifth toe of Peteinosaurus was long and clawless. Its joint allowed it to flex in a different plane than the other phalanges, an adaptation whose function is unknown. Peteinosaurus is one of the oldest-known pterosaurs, and at a mere sixty centimetres, had a tiny wingspan when compared to some later genera, such as Pteranodon whose wingspan exceeded twenty feet. Its wings were also proportionally smaller than those of later pterosaurs, as its wing length was only twice the length of the hindlimb. All other known pterosaurs have wingspans at least three times the length of their hindlimbs. It also had single cusped teeth that lacked the specialized heterodonty present in the other Italian Triassic pterosaur genus, Eudimorphodon. All these factors converge to hint that Peteinosaurus belongs to a group that possibly represents the most basal known pterosaurs: the Dimorphodontidae, to which it was assigned in 1988 by Robert L. Carroll. The only other known member of that group is the later genus Dimorphodon, which lent its name to the family including both genera. Later cladistic analyses however, have not shown a close connection between the two forms. Nevertheless the possible basal position of Peteinosaurus has been affirmed by Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia who suggested that Preondactylus, according to David Unwin the most basal pterosaur, might be a subjective junior synonym of Peteinosaurus. A 2010 cladistic analysis by Brian Andres and colleagues placed Peteinosaurus in Lonchognatha which includes Eudimorphodon and Austriadactylus as more basal.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Триас, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, диморфодонтиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| March 9th, 2012 | |

| 05:20 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Eudimorphodon Eudimorphodon was a pterosaur that was discovered in 1973 by Mario Pandolfi near Bergamo, Italy and described the same year by Rocco Zambelli. The nearly complete skeleton was retrieved from shale deposited during the Late Triassic (mid to late Norian stage), making Eudimorphodon the oldest pterosaur then known. It had a wingspan of about 100 centimetres (3.3 ft) and at the end of its long bony tail may have been a diamond-shaped flap like in the later Rhamphorhynchus. If so, the flap may have helped it steer while maneuvering in the air. Eudimorphodon is known from several skeletons, including juvenile specimens. Eudimorphodon showed a strong differentiation of the teeth, hence its name, which is derived from ancient Greek for "true dimorphic tooth". It also possessed a large number of these teeth, a total of 110 of them densely packed into a jaw only six centimeters long. The front of the jaw was filled with fangs, per side four in the upper jaw, two in the lower jaw, that rather abruptly gave way to a line of smaller multipointed teeth, 25 in the upper jaw, 26 in the lower jaw, most of which had five cusps, others three or even four. The morphology of the teeth are suggestive of a piscivorous diet, which has been confirmed by preserved stomach contents containing the remains of fish of the genus Parapholidophorus. Young Eudimorphodon had slightly differing dentition with fewer teeth and may have had a more insectivorous diet. The top and bottom teeth of Eudimorphodon came into direct contact with each other when the jaws were closed, especially at the back of the jaw. This degree of dental occlusion is the strongest known among pterosaurs. The teeth were multi-cusped, and tooth wear shows that Eudimorphodon was able to crush or chew its food to some degree. Wear along the sides of these teeth suggests that Eudimorphodon also fed on hard-shelled invertebrates. Despite its great age Eudimorphodon has few primitive characteristics making the taxon of little use in attempting to ascertain where pterosaurs fit in the reptile family tree. Basal traits though, are the retention of pterygoid teeth and the flexibility of the tail, which lacks the very long stiffening vertebral extensions other long-tailed pterosaurs possess. Paucity of early pterosaur remains has ensured that their evolutionary origins continues to be a persiseant mystery with some experts suggesting affinities to dinosaurs, archosauriformes, or prolacertiformes. Within the standard hypothesis that the Dinosauromorpha are the pterosaurs' close relatives within an overarching Ornithodira, Eudimorphodon is also unhelpful in establishing relationships within Pterosauria between early and later forms because then its multicusped teeth should be considered highly derived, compared to the simpler single-cusped teeth of Jurassic pterosaurs, and a strong indicator that Eudimorphodon is not closely related to the ancestor of later pterosaurs. Instead it is believed to be a member of a specialized off branch from the main "line" of pterosaur evolution, the Campylognathoididae. Eudimorphodon currently includes two species. The type species, E. ranzii, was first described by Zambelli in 1973. It is based on holotype MCSNB 2888. The specific name honours Professor Silvio Ranzi. A second species, E. rosenfeldi, was named by Dalla Vecchia in 1995 for two specimens found in Italy. However, further study by Dalla Vecchia found that these actually represented a distinct genus, which he named Carniadactylus in 2009. One additional species is still currently recognized: E. cromptonellus, described by Jenkins and colleagues in 2001. It is based on a juvenile specimen with a wing span of just 24 centimeters, MGUH VP 3393, found in the early nineties in Greenland. Its specific name honors Professor Alfred W. Crompton; the name is a diminutive because the exemplar is so small. In 1986 fossil jaw fragments containing multicusped teeth were found in Dockum Group rocks in western Texas. One fragment, apparently from a lower jaw, contained two teeth, each with five cusps. Another fragment, from an upper jaw, also contained several multi-cusped teeth. These finds are very similar to Eudimorphodon and may be attributable to this genus, although without better fossil remains it is impossible to be sure.

Репродукции (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9):

( Далее )

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Триас, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 05:06 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Caviramus Caviramus is a genus of "rhamphorhynchoid" pterosaur from the Late Triassic (late Norian-early Rhaetian-age) lower Kössen Formation of the Northern Calcareous Alps of Switzerland. The genus was in 2006 named by Nadia Fröbisch and Jörg Fröbisch. The type species is Caviramus schesaplanensis. The genus name is derived from Latin cavus, "hollow" and ramus, "branch". The specific name refers to Mount Schesaplana. The genus is based on holotype PIMUZ A/III 1225, three non-contiguous fragments of a ramus (lower jaw) of the mandible with multicuspate teeth. Two teeth are preserved, one with three cusps, and one with four; despite this difference the authors consider them as essentially isodont. The number of teeth is estimated at a minimum of twelve and a maximum of seventeen. A row of large oval foramina runs parallel to the tooth row; foramina in the form of small holes in the anterior part of the lower jaw suggest some sort of soft-tissue structure, or a keratin covering. The jaw is light and hollow. The teeth of this genus resemble those of Eudimorphodon, but the jaw is different. The discovery of this genus is a find of some significance, as there are few pterosaurs known from the Triassic. A second specimen, originally assigned to its own genus and species as Raeticodactylus filisurensis, consists of a single disarticulated partial skeleton including an almost complete skull. The skull shows that it had a tall thin bony crest running along the midline of the front of the upper jaw, and a keel on the lower jaw. The teeth at the front of the upper jaw, in the premaxillae, were fanglike, whereas the teeth in the upper cheeks (the maxillae) had three, four, or five cusps, similar to those of Eudimorphodon. Caviramus had a wingspan of about 135 centimeters (53 in), and may have been a piscivore, potentially a dip-feeder. Despite the resemblance to Eudimorphodon the authors classified Caviramus as Pterosauria incertae sedis. A 2009 study by Fabio Dalla Vecchia concluded that Raeticodactylus, which is known from a more complete skeleton including lower jaw, probably belong to the same genus, and possibly the same species, if the differences (such as size and the presence of a crest in the Raeticodactylus specimen) are not due to sex or age. Subsequent studies have supported their synonymy. Dalla Vecchia found the two forms in a sister clade of Carniadactylus, implying that Caviramus was a member of the Campylognathoididae.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Триас, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

| 04:55 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Austriadactylus Austriadactylus is a genus of "rhamphorhynchoid" pterosaur. The fossil remains were unearthed in Late Triassic rocks of Austria. The genus was named in 2002 by Fabio Marco Dalla Vecchia e.a.. The type species is Austriadactylus cristatus. The genus name is derived from Latin Austria and Greek daktylos, "finger", in reference to the wing finger of pterosaurs. The specific epithet means "crested" in Latin, a reference to the skull crest. The genus is based on holotype SMNS 56342, a crushed partial skeleton on a slab, found in an abandoned mine near Ankerschlag in Tirol, in the Norian Seefelder Beds. The counterslab has been lost and with it some of the bone. The fossil consists of the skull, lower jaws, some vertebrae, parts of the limbs and pelvic girdle, and the first part of the tail. The elongated skull has a length of eleven centimetres. It carried a bony crest that widened as it descended towards the snout, up to height of two centimetres. The triangular nares formed the largest skull openings. The also triangular fenestrae antorbitales are smaller that the orbits. The teeth differ in shape and the species was thus heterodont. Most teeth are small and tricuspid or three-pointed. In the front of the upper jaw five larger recurved teeth with a single point form a prey grab; six or seven such teeth are also interspersed with the smaller teeth more to the back of the mouth. There are at least seventeen and perhaps as much as 25 tricuspid teeth in the upper jaw, for a total of perhaps 74 teeth of all sizes in the skull. The number of teeth in the lower jaws cannot be determined. The flexible tail did not have the stiffening rod-like vertebral extensions present in other basal pterosaurs. The wingspan has been estimated at about 120 centimetres. Austriadactylus was in 2002 assigned by the describers to a general Pterosauria incertae sedis, but some later analyses showed it to have been related to Campylognathoides and Eudimorphodon in the Campylognathoididae. It has even been suggested it was a junior synonym of Eudimorphodon, though perhaps a distinct species in that genus.

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Триас, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, птерозавры, рамфоринхоидеи |

/006_Sordes.jpg)

.JPG)