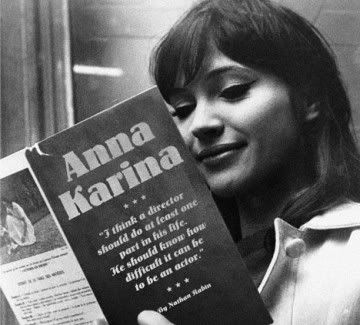

Interviewed by Nathan Rabin

May 14th, 2003

With her big, expressive eyes and radiant presence, French New Wave icon Anna Karina hearkened back to the heyday of silent film while simultaneously embodying the brash new spirit of the '60s. That combination made her the perfect symbol for a movement that reinvigorated and revolutionized film while paying frequent homage to its forebears. Born in Denmark, Karina moved to France and began working as a model while she was still a teenager. Her ads drew the attention of Jean-Luc Godard, who later became her husband and regular collaborator. The duo first worked together on The Little Soldier, a controversial treatise on France's Algerian War that was shelved for years due to its incendiary content. After The Little Soldier's production but before its 1963 release, Karina appeared in a number of films, most notably A Woman Is A Woman, Godard's ebullient tribute to musicals and the comedies of Ernst Lubitsch. The film won Karina the Best Actress award at the 1961 Berlin Film Festival and helped pave the way for her singing career. Godard and Karina divorced in 1964, but their professional partnership continued, and together they created some of the French New Wave's most beloved films, including 1965's Alphaville and 1964's Band Of Outsiders (Bande À Part), whose dance sequence ranks as one of the most imitated scenes in film history. Godard's collaboration with Karina ended with a segment in the 1967 anthology The Oldest Profession; that same year, she collaborated with Serge Gainsbourg on Anna, a television special and album. Karina also worked with directors like Luchino Visconti (The Stranger), George Cukor (Justine), and Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Chinese Roulette), and in 1973, she wrote, directed, and starred in her own film, Living Together. These days, Karina continues to release albums, perform concerts, and act in television and film, appearing recently in Jonathan Demme's French New Wave homage The Truth About Charlie. In conjunction with the re-release of A Woman Is A Woman, The Onion A.V. Club spoke to Karina about her show-business beginnings, her early experiences with Godard, and why actors should spend eight hours a day in front of a mirror.

The Onion: What led to your move to France, and what was it like once you got there?

Anna Karina: It's a long story. My God, it was so many years ago. Well, it was because I had some kind of family problem with my stepfather. I came to France and of course I had no money, so I went to the Danish Church, and the priest gave me a little room and so-and-so. I worked drawing on streets and things like that. Then a lady asked me if I wanted to do some pictures. So I asked, "What kind of pictures?" because I was a little suspicious about that. She said it was for fashion, so I took the pictures, and to make a short story right out of the long story, I earned a little money, too. I kept my money to go to school and learn French and all that. Also, I went to the movies and saw the pictures with Jean Gabin. I learned–how to say–they had this special language which they call argot here. You understand? I saw all the films where they would talk a bit of French, so after a while I would understand that when somebody said to a woman, "Okay, goodbye," it meant the same thing as "Goodbye, lady." I learned that in cinema, there were two kinds of languages.

O: Did you enjoy being a model? Was it hard work?

AK: No, I didn't like that too much, because I'm somebody who can't stay too long time in front of a picture. I like to move, so they always told me, "Okay, you're not really meant to do that, because you're moving too much." When you're a model, you have to do–at the time, it was like, I don't know how to say... It was not something that I was really very interested in. What was good for me was that I could earn some money, since I didn't have any, and it was a big chance for me, so I'm not saying it was a bad thing. You understand what I mean? I also did the publicity films and things like that. Like, you know, films for soap and Coca-Cola and Pepsodent, and that kind of thing. That's how Jean-Luc Godard saw me, in one of the soap films. Because actually I did two of them. I did Palmolive and Monsavon, which is two soap films, and you can't do two at the same time. I was underage, see, so I didn't really know. I didn't realize that you're not supposed to do two soap films at the same time. Because on one side of the Champs-Elysées there was Monsavon, and on the other there was Palmolive. But I hadn't signed anything, because I was underage, so they couldn't take me to court for it. I didn't do it on purpose, really; I just didn't know that you couldn't do that type of thing. I didn't sign anything, and my mother didn't sign anything, either, because she was in Denmark. See, I was born in Copenhagen. So I was still underage, because at that time you had to be over 21. I was about 18. So one day, Jean-Luc Godard, who did of course A Woman Is A Woman, he asked me if I could see him. He was in an office, and he said to me, "Well, it's for a little part in Breathless," which was his first film. So I said, "Okay, what do I have to do?" He said, "Well, you have to play a part about a girl taking her clothes off." I said, "I don't want to take my clothes off." So that was the end of the first meeting with Jean-Luc Godard.

O: What did you think of him?

AK: I thought that he was very strange, because of his dark glasses and all that, and asking a young girl to take her clothes off. At that time, it was kind of suspicious and bizarre, I thought. I was not used to doing that kind of thing, so I said "No, no, no" for that little part. And then, of course, my friends afterwards said, "So, you know this guy Jean-Luc has done so-and-so with Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo." And I said, "What does he look like?" They said, "Well, he's kind of a special guy with dark glasses." So I said, "Ah, yes, I know him." About three months later, I got a telegram saying, "Would you like to come to the office and see Jean-Luc Godard for another part?" I said to my friends, "Jean-Luc Godard must be a joke, because he's saying this time it might be for the main part." Why would he want little old me to do the main part, this man with the dark glasses? Because you have to understand, at this point, nobody was wearing dark glasses. It's not like today, with all the rock stars and everybody wearing dark glasses. At that moment, it was very special. So of course I could remember him because of the dark glasses, because I never saw his eyes. They said I had to go, because he had just done a fantastic film with Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul BelmondO: "You have to see this guy again." So [Godard] looked at me and said, "Okay, you're playing the part." I said, "What's it about?" And he said, "Well, don't worry. It's a political part. It's a political film." I knew nothing about politics, but he said it didn't matter, that I shouldn't worry. I said I couldn't get up and make a speech or something like that. He said, "Don't worry about that. You don't have to make a speech." I said, "Do I have to take my clothes off? I don't want to take my clothes off." He said, "No, you don't have to take your clothes off. You just have to come tomorrow morning and sign your contract." I said, "Tomorrow morning, I can't do that." He said, "Why?" I said, "Well, I'm underage." He said, "You can come with your mother." I said, "She's not in France, she's in Copenhagen." And he said, "Oh, trouble again. Just phone your mother or something, tell your mother to come." So I phoned my mother, and still we were not in very good shape at that time. I was still a little bit angry at my mother. So I said, "Mother, I'm playing the main part in a political film." She said, "What?" I said, "I'm playing the main part." But she didn't believe that. She thought I was so full of shit, and she hangs up. So I called again and said, "Mother, you have to understand this, this is serious. You have to come to Paris and sign my contract, and you have to come as quick as possible, because I don't want this guy to change his mind. It's all out of the blue, but I want to do it." And she was like, "What is all this shit about?" I said, "You have to believe me, Mother. You have to take the plane." So she came in and signed the contract. That's how I got involved with The Little Soldier, which was my first film with Jean-Luc Godard.

O: Did you have any formal training as an actress?

AK: Well, I did my first picture when I was 14 and a half. I'm going back to Denmark now, right? My mother, she was doing costumes at that time. One day, when I was 14, a guy in the street saw me and said, "Would you like to maybe play in my film?" I said, "I don't know, you'll have to ask my mother about that." I always wanted to be an actress ever since I was a little girl, but I was 14. So he went to see my mother, and I had to do some kind of... How do you say when you have to go to casting?

O: Audition?

AK: Yeah, like film casting, to see if you're right for the part. Yes, film audition. So my mother said yes, and I got the part. That little short film won the prize in Cannes afterwards. So that was the first time I was involved with the movies. Then I did lots afterwards, but I was very young, so I didn't get so many parts, you can understand that. Now, when you're very young, it's much better, but at that time, I was too young. So I was a little bit painting, things like that, because I left school when I was 14. I was doing illustrations, things like that. You know, for a painter, I was an assistant, and then he knew a lot of movie people. So, how do you say in English, I was an extra. I'm in a lot of Danish pictures as an extra. When I left for France, I didn't speak French–I spoke a little bit of English like I do now, and then I had to learn. Like I said before, I went to movie houses and had a teacher and all that, and then I did all the pictures that were going on for six months. I earned a lot of money for six months. It was incredible. I did the publicity for the Coca-Cola and Pepsodent, and what else? I don't remember. That's how I met Jean-Luc Godard, as I just told you the story.

O: You mentioned that you didn't know a lot about politics when you made The Little Soldier. Did you become more interested in politics later on?

AK: I was 18 years old in a foreign country. There was a war in Algiers. I didn't understand when I was living there why people were shot in the streets and all that. We didn't have TV at the time. We didn't have the same information. I knew that there was a war, but it was going on in Algiers. We didn't have all that information, and of course I was not reading the papers, because my French was not good enough, so I didn't really understand that much about it. Still I don't. Still I don't know why people are doing wars. For me it's the horror, it's terrifying, but it doesn't mean that I don't read the papers now and look at the TV. At the time, it's so many years ago.

O: When you were married to Godard, did you become more interested in politics?

AK: Well, I think life is politics anyway. You can't ignore it, but you can go very wrong in politics. You can say what you thought 50 years ago, but maybe you're wrong today. It's something very special, politics. I think you'd better be a good person in life every day–it's much more important.

O: What was Godard's process like?

AK: It was absolutely for me fantastic. We did The Little Soldier, of course, and we were working without the script, but he would tell you about it. He would explain it to you, and we would rehearse a lot before we filmed anything, because he was always very big on the rehearsal. He uses very little film. I guess he never did over 15,000 meters of film. Some people need a lot of film, but Jean-Luc would rehearse a lot and film very little.

O: Was it stressful, not having a script that you could memorize in advance?

AK: You know, some people have scripts and scripts and lots of scripts, and they change it all the time. Even though he had no script, he had it all in his heart and in his brain. He can explain it to you in a way where even if you get the dialogue five minutes before in the morning and you have to shoot it later, at least you have an idea about it, because he takes his time to explain things and to do the movements with you. There's always lots of rehearsal. Many other directors, they have lots of scripts and they never rehearse as much, and you never really have time to be a part of it. With Jean-Luc, you always had time to be a part of it. It's difficult to explain to normal people. Normal people, they don't understand that. Even if it's not written down, it's still there. How do you explain that?

O: Did other filmmakers you worked with use the same methods as Godard?

AK: No. Everybody, even all the people with talent and genius, they had their own kind of way. But there is one way they are all the same: They're very human, and they have this sense of giving to you. It doesn't matter what kind of way they're doing it, as long as it's getting to you–as long as you're on the same road.

O: How was working with Fassbinder, for example?

AK: That was really strange. He's a guy who's a little like Jean-Luc. He was most special, in a way. How I can explain that? It was not as clear as with Jean-Luc, because even though Jean-Luc never had a script, it was always clear. It was not that we would say, "What is this film? We don't understand anything." No, we did understand everything. That was the genius of Jean-Luc Godard, that he did make you understand everything, even though it wasn't written down. Everybody always understood what he wanted to do. With Fassbinder, it was kind of different. Even though he had a script, he would change it, and there were not so many rehearsals. With Jean-Luc, even though everyone always said it was all improvised, that is absolutely not true, you know. We always had the time to rehearse the scene. That means you can get into the scene with your legs, with your body, with your mind. You had the time to get into the character you're playing.

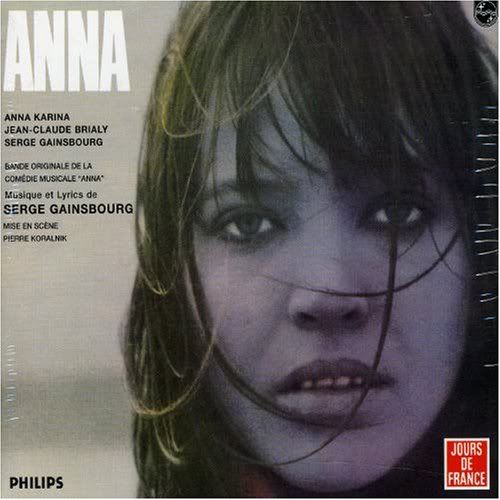

O: What was it like working with Serge Gainsbourg?

AK: That was great. We had really great fun. It was very serious and fun, too. He was such a great person. He was not the person he would become later, at that time. He was very timid and full of fun, and a little bit cynical, too, I must say. We would go and dance and have fun all the time. He was not such a big star at the time. At that time, we would go with Godard and eat cheese or something. We both loved eating cheese–you know the French, we're famous for the cheese with the red wine. We'd rehearse, he had this big studio with a big piano, and that was about it. I suppose he had a bedroom, too, but I never saw it. I really loved it, working with Serge. We had a very good, how do you say, relationship.

O: In the '70s, you wrote and directed a film yourself. How did that come about?

AK: I wanted to do it. I had this sudden urge to do a film myself. At that time, it was pretty difficult, because actresses didn't really do films. It was like, "What's wrong with her? Why would she want to do a picture?" Things like that. I think a director should do at least one part in his life. He should know how difficult it can be to be an actor. An actor should do at least a short film in his life, so he can know how difficult it is to be a director. Maybe they would understand each other better. I really wanted to do this film, so I wrote the script, but I thought nobody would want to produce it, so I produced it myself with very little money.

O: What was it like making A Woman Is A Woman?

AK: It was absolutely fantastic. I loved doing that movie, because it was a comedy. I'd done A Little Soldier with Jean-Luc, and then it was banned for two years. In between, I did another film called Tonight Or Never with Michel Deville, and then Jean-Luc saw the film and asked me if I wanted to do A Woman Is A Woman with Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean-Claude Brialy. I said, "Oh, yes, I would love that." And he said, "Well, you have to sing in the film, and it's about a girl doing striptease, but it's not the kind of striptease where you have to be completely nude." He told me the story and all that, and we made the film, and actually that was my big chance, because I got the prize in Berlin for Best Actress, and I was the youngest actress at the time to get the prize in Berlin. So that was a big, big, big thing.

O: Why do you think so many filmmakers have been inspired by the French New Wave, and more specifically by the films you made with Godard?

AK: I guess they liked it. I'm very flattered. You know, Tarantino called his production company A Band Apart, which is a film that Jean-Luc made.

O: And in Pulp Fiction, Uma Thurman's character's hair is clearly modeled on yours in Bande À Part.

AK: Yes, it's very flattering. Also, George Cukor, when I worked with him in Justine in the '70s, he knew about Jean-Luc very, very much. He knew everybody. He taught me so much, George Cukor. I loved to work with George, because he would say to me, "Anna, if you take the dialogue, and you say it in an angry way, and in a timid way, in a lovely way, if you say it all kinds of ways that you think of–you know, arrogant, everything–then, when you've slept all night, the next morning, everything will come back to you. Then you can really do the part with a lot of small differences." Do you understand what I'm saying? Oh, my English, it is not good enough. Then, you see, you get a lot more out of your character, because you've done all that work at home. Jean-Luc would say that an actor had to work in front of his mirror every day for eight hours. And [the actors] would sit there, because we were very young at the time, and we would laugh and say, "What do you mean by that?" And he would say, "Don't you understand that if somebody is going to work, he's going to work at least eight hours a day? Why would you not work eight hours a day in front of your mirror to learn about yourself, to learn about what you're doing, to learn how ridiculous you can be, how good you can be, how stupid you can be, and so-and-so?" Of course, he was right that we should all do that every day, even when we're not working, because after all, everybody's working eight hours a day.