[Recent Entries][Archive][Friends][User Info]

| October 10th, 2012 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 08:24 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Diplodocus Диплодо́к (Diplodocus) — род ящеротазовых динозавров из группы зауропод. Первый окаменелый скелет был найден в 1877 году в Скалистых горах (Колорадо) палеонтологом С. У. Уилистоном (Samuel Wendell Williston). Позже были обнаружены и другие останки в отложениях юрского периода (формация Моррисон). Все они датируются возрастом 150—147 млн лет назад. Является крупнейшим из динозавров, известных по полным скелетам. Название рода происходит от греческих слов διπλόος — «сдвоенная» и δοκός — «Балка», дано из-за двойных нижних остистых отростков позвонков. Один из самых больших динозавров позднеюрского периода. Диплодок достигал в длину 27 метров, но по мнению ученых размеры самых крупных особей могли и вовсе достигать 35 метров. Из них большая часть приходилась на шею и хвост. Кости шеи и хвоста у диплодока были полыми. Вес диплодока по одним оценкам составлял 10—20 тонн, а по другим достигал 20—80 тонн. Диплодок имел длинную шею, состоящую из 15 позвонков, возможно, заполненных сообщающимися воздушными мешками. Череп диплодока имел непарное носовое отверстие, расположенное не на кончике морды, а в верхней части головы впереди глаз. Зубы в форме узких лопаточек имелись только в передней части рта. Конечности диплодока были пятипалыми, с короткими массивными когтями на внутренних пальцах. Длинный хвост диплодока, заканчивавшийся тонким «хлыстом», служил прекрасным орудием защиты. Вероятно, диплодоки вели стадный образ жизни, питаясь листьями невысоких деревьев. Не умея жевать, они заглатывали камни, которые помогали им перетирать пищу. Подобно брахиозавру, диплодок передвигался на четырех ногах, причём задние были длиннее передних. За период с 1878 по 1924 годы было описано несколько видов, относящихся к роду Диплодок. Первый скелет обнаружили Benjamin Mudge и Samuel Wendell Williston в 1878 году на западе США, в штате Вайоминг. По этому экземпляру известный палеонтолог того времени Г. Марш описал новый вид, назвав его Diplodocus longus. Впоследствии фоссилии диплодоков были найдены и на территории других западных штатов: Колорадо, Юта и Монтана. В музее естественной истории Карнеги находится череп юного диплодока. Этот маленький череп был обнаружен в 1921 году. Исследовав его, специалисты по палеонтологии в 2010 году пришли к выводу, что форма головы диплодока сильно менялась по мере роста. Известно несколько видов диплодоков, все виды — растительноядные формы. В современных классификациях к диплодокам относят также сейсмозавра (Diplodocus hallorum). Diplodocus is among the most easily identifiable dinosaurs, with its classic dinosaur shape, long neck and tail and four sturdy legs. For many years, it was the longest dinosaur known. Its great size may have been a deterrent to the predators Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus: their remains have been found in the same strata, which suggests they coexisted with Diplodocus. One of the best-known sauropods, Diplodocus was a very large long-necked quadrupedal animal, with a long, whip-like tail. Its forelimbs were slightly shorter than its hind limbs, resulting in a largely horizontal posture. The long-necked, long-tailed animal with four sturdy legs has been mechanically compared with a suspension bridge. In fact, Diplodocus is the longest dinosaur known from a complete skeleton. The partial remains of D. hallorum have increased the estimated length, though not as much as previously thought; when first described in 1991, discoverer David Gillette calculated it may have been up to 54 m (177 ft) long, making it the longest known dinosaur (excluding those known from exceedingly poor remains, such as Amphicoelias). Some weight estimates ranged as high as 113 tons (125 US short tons). The estimated length was later revised downward to 33 metres (108 ft) based on findings that show that Gillette had originally misplaced vertebrae 12–19 at vertebrae 20–27. The nearly-complete Diplodocus skeleton at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on which estimates of Seismosaurus are based, also was found to have had had its 13th tail vertebra come from another dinosaur, throwing size estimates for Seismosaurus further off. While dinosaurs such as Supersaurus were probably longer, fossil remains of these animals are only fragmentary. Modern mass estimates for Diplodocus (exclusive of D. hallorum) have tended to be in the 10 to 16 tonne (11–17.6 ton) range: 10 tonnes (11 tons); 11.5 tonnes (12.7 tons); 12.7 tonnes (14 tons); and 16 tonnes (17.6 tons). The skull of Diplodocus was very small, compared with the size of the animal, which could reach up to 35 m (115 ft), of which over 6 m (20 ft) was neck. Diplodocus had small, 'peg'-like teeth that pointed forward and were only present in the anterior sections of the jaws. Its braincase was small. The neck was composed of at least fifteen vertebrae and is now believed to have been generally held parallel to the ground and unable to have been elevated much past horizontal. Diplodocus had an extremely long tail, composed of about 80 caudal vertebrae, which is almost double the number some of the earlier sauropods had in their tails (such as Shunosaurus with 43), and far more than contemporaneous macronarians had (such as Camarasaurus with 53). There has been speculation as to whether it may have had a defensive or noisemaking (by cracking it like a coachwhip) function. The tail may have served as a counterbalance for the neck. The middle part of the tail had 'double beams' (oddly shaped bones on the underside, which gave Diplodocus its name). They may have provided support for the vertebrae, or perhaps prevented the blood vessels from being crushed if the animal's heavy tail pressed against the ground. These 'double beams' are also seen in some related dinosaurs. Like other sauropods, the manus (front "feet") of Diplodocus were highly modified, with the finger and hand bones arranged into a vertical column, horseshoe-shaped in cross section. Diplodocus lacked claws on all but one digit of the front limb, and this claw was unusually large relative to other sauropods, flattened from side to side, and detached from the bones of the hand. The function of this unusually specialized claw is unknown Valid species: D. carnegii (also spelled D. carnegiei), named after Andrew Carnegie, is the best known, mainly due to a near-complete skeleton collected by Jacob Wortman, of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and described and named by John Bell Hatcher in 1901. D. hayi, known from a partial skeleton discovered by William H. Utterback in 1902 near Sheridan, Wyoming, was described in 1924. D. hallorum, first described in 1991 by Gillette as Seismosaurus halli from a partial skeleton comprising vertebrae, pelvis and ribs. George Olshevsky later attempted to emend the name as S. hallorum, citing incorrect grammar on the part of the original authors, a recommendation that has been followed by others, including Carpenter (2006). In 2004, a presentation at the annual conference of the Geological Society of America made a case for Seismosaurus being a junior synonym of Diplodocus. This was followed by a much more detailed publication in 2006, which not only renamed the species Diplodocus hallorum, but also speculated that it could prove to be the same as D. longus. The position that D. hallorum should be regarded as a specimen of D. longus was also taken by the authors of a redescription of Supersaurus, refuting a previous hypothesis that Seismosaurus and Supersaurus were the same. Marsh and then Hatcher assumed the animal was aquatic, because of the position of its nasal openings at the apex of the cranium. Similar aquatic behavior was commonly depicted for other large sauropods such as Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus. However, a 1951 study by Kenneth A. Kermack indicates that sauropods probably could not have breathed through their nostrils when the rest of the body was submerged, as the water pressure on the chest wall would be too great. Since the 1970s, general consensus has the sauropods as firmly terrestrial animals, browsing on trees, ferns and bushes. The depiction of Diplodocus posture has changed considerably over the years. For instance, a classic 1910 reconstruction by Oliver P. Hay depicts two Diplodocus with splayed lizard-like limbs on the banks of a river. Hay argued that Diplodocus had a sprawling, lizard-like gait with widely splayed legs, and was supported by Gustav Tornier. However, this hypothesis was contested by W. J. Holland, who demonstrated that a sprawling Diplodocus would have needed a trench to pull its belly through. Finds of sauropod footprints in the 1930s eventually put Hay's theory to rest. Later, diplodocids were often portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to graze from tall trees. Studies using computer models have shown that neutral posture of the neck was horizontal, rather than vertical, and scientists such as Kent Stephens have used this to argue that sauropods including Diplodocus did not raise their heads much above shoulder level. However, subsequent studies demonstrated that all tetrapods appear to hold their necks at the maximum possible vertical extension when in a normal, alert posture, and argued that the same would hold true for sauropods barring any unknown, unique characteristics that set the soft tissue anatomy of their necks apart from other animals. One of the sauropod models in this study was Diplodocus, which they found would have held its neck at about a 45 degree angle with the head pointed downwards in a resting posture. As with the related genus Barosaurus, the very long neck of Diplodocus is the source of much controversy among scientists. A 1992 Columbia University study of Diplodocid neck structure indicated that the longest necks would have required a 1.6 ton heart — a tenth of the animal's body weight. The study proposed that animals like these would have had rudimentary auxiliary 'hearts' in their necks, whose only purpose was to pump blood up to the next 'heart'. While the long neck has traditionally been interpreted as a feeding adaptation, it was also suggested that the oversized neck of Diplodocus and its relatives may have been primarily a sexual display, with any other feeding benefits coming second. However, a recent study refuted this idea in detail Diplodocus has highly unusual teeth compared to other sauropods. The crowns are long and slender, elliptical in cross-section, while the apex forms a blunt triangular point. The most prominent wear facet is on the apex, though unlike all other wear patterns observed within sauropods, Diplodocus wear patterns are on the labial (cheek) side of both the upper and lower teeth. What this means is Diplodocus and other diplodocids had a radically different feeding mechanism than other sauropods. Unilateral branch stripping is the most likely feeding behavior of Diplodocus, as it explains the unusual wear patterns of the teeth (coming from tooth–food contact). In unilateral branch stripping, one tooth row would have been used to strip foliage from the stem, while the other would act as a guide and stabilizer. With the elongated preorbital (in front of the eyes) region of the skull, longer portions of stems could be stripped in a single action. Also the palinal (backwards) motion of the lower jaws could have contributed two significant roles to feeding behaviour: 1) an increased gape, and 2) allowed fine adjustments of the relative positions of the tooth rows, creating a smooth stripping action In 2010, Whitlock et al. described a juvenile skull of Diplodocus (CM 11255) that differs greatly from adult skulls of the same genus: its snout is not blunt, and the teeth are not confined to the front of the snout. These differences suggest that adults and juveniles were feeding differently. Such an ecological difference between adults and juveniles had not been previously observed in sauropodomorphs. Recent discoveries have suggested that Diplodocus and other diplodocids may have had narrow, pointed keratinous spines lining their back, much like those on an iguana. It is unknown exactly how many diplodocids had this trait, and whether it was present in other sauropods. While there is no evidence for Diplodocus nesting habits, other sauropods such as the titanosaurian Saltasaurus have been associated with nesting sites. The titanosaurian nesting sites indicate that may have laid their eggs communally over a large area in many shallow pits, each covered with vegetation. It is possible that Diplodocus may have done the same. Following a number of bone histology studies, Diplodocus, along with other sauropods, grew at a very fast rate, reaching sexual maturity at just over a decade, though continuing to grow throughout their lives. Previous thinking held that sauropods would keep growing slowly throughout their lifetime, taking decades to reach maturity. Comparisons between the scleral rings of Diplodocus and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been cathemeral, active throughout the day at short intervals. Diplodocus is both the type genus of, and gives its name to Diplodocidae, the family to which it belongs. Members of this family, while still massive, are of a markedly more slender build when compared with other sauropods, such as the titanosaurs and brachiosaurs. All are characterised by long necks and tails and a horizontal posture, with forelimbs shorter than hindlimbs. Diplodocids flourished in the Late Jurassic of North America and possibly Africa. A subfamily, Diplodocinae, was erected to include Diplodocus and its closest relatives, including Barosaurus. More distantly related is the contemporaneous Apatosaurus, which is still considered a diplodocid although not a diplodocine, as it is a member of the subfamily Apatosaurinae. The Portuguese Dinheirosaurus and the African Tornieria have also been identified as close relatives of Diplodocus by some authors. The Diplodocoidea comprises the diplodocids, as well as dicraeosaurids, rebbachisaurids, Suuwassea, Amphicoelias and possibly Haplocanthosaurus, and/or the nemegtosaurids. This clade is the sister group to, Camarasaurus, brachiosaurids and titanosaurians; the Macronaria.

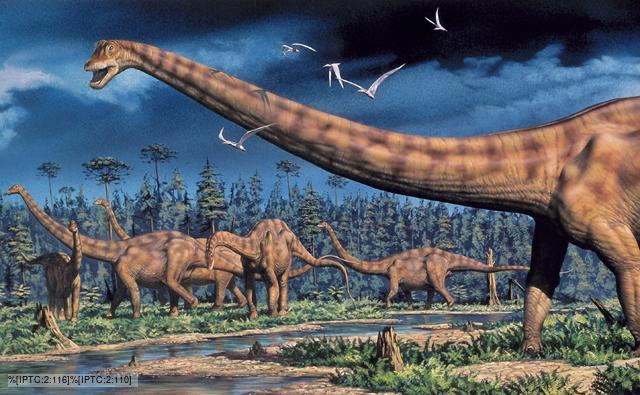

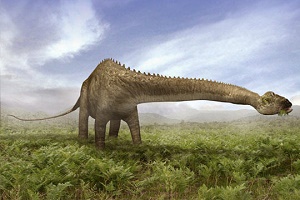

Репродукции (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12):

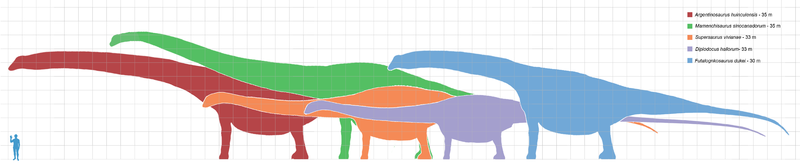

Размеры тела в сравнении с другими гигантскими завроподами и человеком (закрашен зелёным цветом):

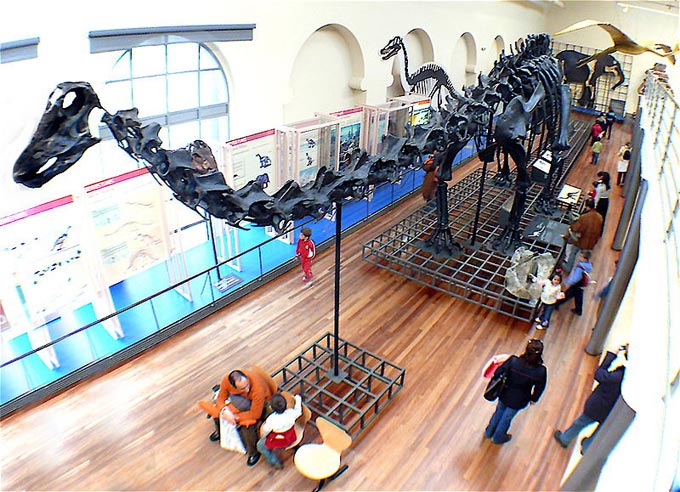

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8):

Tags: Вымершие рептилии, Юра, авеметатарзалии, архозавроморфы, архозавры, диапсиды, динозавроморфы, динозавры, диплодоциды, завроподоморфы, завроподы, ящеротазовые | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Comments | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

жопой думал как ты ты тоже жопой думаеш всегда (Reply to this) (Thread)

Аноним хуже пидораса и перестал думать жопой. С чем мы его и поздравляем. (Reply to this) (Parent)

В Норильске много таких было, потом вымерли все. Холод. (Reply to this) (Thread)

Кто вымер, анон? (Reply to this) (Parent)

"Палеонтологи описали череп юного диплодока, который был обнаружен в 2010 году в США. Как рассказывается в Scientific Reports, ученые прозвали динозавра Эндрю и обнаружили, что у него, по сравнению со взрослыми особями, была короткая и узкая морда и лопатообразные зубы, которые позволяли молодому диплодоку разнообразить свой рацион, и кормиться в лесу, а не на открытых пространствах. Род гигантских динозавров из группы зауропод — диплодоки — обитали на планете в конце юрского периода, примерно 146-156 миллионов лет назад. Предположительно, они достигали в длину 32 метров и могли весить 12 тонн. Диплодоки были травоядными, но, по разным оценкам, они либо в основном кормились травой, либо добавляли к рациону листья, ветки и кору деревьев. Вытянув шею, ящеры доставали до четырехметровой высоты. Возможно, они могли вставать на задние лапы и при этом опираться на хвост, и тогда они могли срывать листву с 11-метровых деревьев. Несколько лет назад палеонтологи описали череп молодого диплодока, у которого, по сравнению со взрослыми особями, была более короткая, узкая и скругленная морда. Тогда авторы предположили, что это могло быть связано с тем, что рацион взрослых и молодых особей различался. В новом исследовании канадские, американские и германские палеонтологи под руководством Кэри Вудраффа (Cary Woodruff) описали еще один череп юного диплодока неизвестного вида, который был найден в 2010 году в штате Монтана на северо-западе США. По оценкам ученых длина черепа составляла около 24 сантиметров. Также, как у описанных ранее молодых диплодоков, у динозавра, которого исследователи прозвали Эндрю, была корокая и узкая морда. Также у него обнаружились лопатообразные зубы и, по сравнению со взрослыми диплодоками, удлиненный ряд зубов. Авторы исследования предположили, что, судя по строению зубов, рацион у молодых динозавров был более разнообразным, чем у взрослых. По-видимому, они питались как грубыми растительными волокнами, так и травой и листьями. По мнению ученых, узкая и короткая морда свидетельствует о том, что юные диплодоки жили и питались, в основном, в лесу, возможно, таким образом укрываясь от хищников, в то время как взрослые особи предпочитали открытые пространства." http://paleonews.ru/new/1137-andrew | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||