[Recent Entries][Archive][Friends][User Info]

Below are the 20 most recent journal entries recorded in the "Сообщество, посвящённое ра" journal:| September 29th, 2011 | |

|---|---|

| 08:13 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Девонское вымирание Девонское вымирание — вымирание видов в позднем Девоне, было одним из крупнейших вымираний в истории земной флоры и фауны. Основное вымирание произошло на границе, которая отмечает начало последней фазы Девонского периода, Фаменского (Famennian) экологического века, (Фраснско — Фаменская (Frasnian-Famennian) граница), около 374 миллионов лет назад, когда почти все бесчелюстные рыбы неожиданно исчезли (их окаменелости в отложениях перестают встречаться). Второй сильный опустошающий импульс завершил Девонский период. Повсюду вымерло 19 % семейств и 50 % всего генофонда. Хотя понятно, что имело место массовое сокращение биоразнообразия к концу Девона, интервал времени, в течение которого это событие происходило, неясен: оценки варьируются от 500 тысяч до 15 миллионов лет, в последнем случае оно продолжалось в течение всего Фаменского века (Famennian). Не совсем понятно, было ли это событие представлено двумя резкими скачками (пиками) массового вымирания или серией из меньших по размеру вымираний, однако результаты последнего исследования скорее указывают на многоэтапное развитие вымирания, из серии отдельных импульсов вымирания на протяжении временного интервала около трёх миллионов лет. Некоторые предполагают, что вымирание состояло по меньшей мере из семи отдельных событий, происходивших в течение 25 миллионов лет, включая наиболее заметные вымирания в конце Живетского (Givetian), Фраснского (Frasnian) и Фаменского (Famennian) веков. Некоторые ссылаются на 250-миллионолетний диапазон, в течение которого вымирания имели место. К позднему Девону суша была полностью освоена и заселена растениями, насекомыми и земноводными, а моря и океаны были полны рыбой. Кроме того, в этот период уже существовали гигантские рифы, сформированные кораллами и строматопороидами. Евроамериканский континент и Гондвана только начали движение друг к другу, чтобы в будущем сформировать суперконтинент Пангею. Вероятно, вымирание в основном затронуло морскую жизнь. Рифообразующие организмы были почти полностью уничтожены, в итоге коралловые рифы возродились только с развитием современных кораллов в Мезозое. Брахиоподы (плеченогие), трилобиты и другие семейства тоже были тяжело затронуты. Причины этого вымирания пока неясны. Основная теория предполагает, что изменения в уровне океана и обеднение океанических вод кислородом послужили главной причиной вымирания жизни в океанах. Возможно, что активатором этих событий послужило глобальное похолодание или обширный океанический вулканизм, хотя падение внеземного тела, такого как комета, тоже вполне возможно. Некоторые статистические исследования морской фауны того времени наводят на мысль, что уменьшение разнообразия было связано, скорее, со спадом в темпе видообразования, чем ростом вымирания.

Tags: Девон, Массовое вымирание |

| 08:04 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Немного девонской ботвы Эволюция наземной растительности девонского периода уже вполне определенно выявлена. Отложения нижнего и среднего девона характеризуются еще низкоорганизованной растительностью, известной под названием «псилофитовой», наиболее типичным представителем которой является примитивное папоротиикообразное — псилофитон.

Tags: Девон, Растительность |

| 07:48 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Chitinozoa Chitinozoa (singular: chitinozoan, plural: chitinozoans) are a taxon of flask-shaped, organic walled marine microfossils produced by an as yet unknown animal. Common from the Ordovician to Devonian periods (i.e. the mid-Paleozoic), the millimetre-scale organisms are abundant in almost all types of marine sediment across the globe. This wide distribution, and their rapid pace of evolution, makes them valuable biostratigraphic markers. Their bizarre form has made classification and ecological reconstruction difficult. Since their discovery in 1931, suggestions of protist, plant, and fungal affinities have all been entertained. The organisms have been better understood as improvements in microscopy facilitated the study of their fine structure, and there is mounting evidence to suggest that they represent either the eggs or juvenile stage of a marine animal. The ecology of chitinozoa is also open to speculation; some may have floated in the water column, where others may have attached themselves to other organisms. Most species were particular about their living conditions, and tend to be most common in specific paleoenvironments. Their abundance also varied with the seasons. Chitinozoa range in length from around 50 to 2000 micrometres. They appear dark to almost opaque when viewed under an optical microscope. External ornamentation is often preserved on the surface of the fossils, in the form of hairs, loops or protrusions, which are sometimes as large as the chamber itself. The range and complexity of ornament increased with time, against a backdrop of decreasing organism size. The earliest Ordovician species were large and smooth-walled; by the mid-Ordovician a large and expanding variety of ornament, and of hollow appendages, was evident. While shorter appendages are generally solid, larger protrusions tend to be hollow, with some of the largest displaying a spongy internal structure. However, even hollow appendages leave no mark on the inner wall of the organisms: this may suggest that they were secreted or attached from the outside. There is some debate about the number of layers present in the organisms' walls: up to three layers have been reported, with the internal wall often ornamented; some specimens only appear to display one. The multitude of walls may indeed reflect the construction of the organism, but could be a result of the preservational process. Immature" or juvenile examples of Chitinozoans have not been found; this may suggest that they didn't "grow", that they were moults (unlikely), or that the fossilisable parts of the organism only formed after the developmental process was complete. Most chitinozoans are found as isolated fossils, but chains of multiple tests, joined from aperture to base, have been reported from all genera. Very long chains tend to take the form of a spring. Occasionally, clusters or condensed chains are found, packed in an organic "cocoon". It is not immediately clear what mode of life was occupied by these improbably shaped fossils, and an answer only becomes apparent after following several lines of reasoning. The fossils' restriction to marine sediments can be taken as sound evidence that the organisms dwelt in the Palæozoic seas - which presents three main modes of life:

An infaunal mode of life can be quickly ruled out, as the fossils are sometimes found in alignment with the depositing current; as nothing attached them to the bottom, they must have fallen from the water column. The ornament of the chitinozoans may cast light on the question. Whilst in some cases a defensive role - by making the vessel larger, and thus less digestible by would-be predators - seems probable, it is not impossible that the protrusions may have anchored the organisms to the sea floor. However, their low-density construction makes this unlikely: perhaps more plausible is that they acted to attach to other organisms. Longer spines also make the organisms more buoyant, by decreasing their Rayleigh number (i.e. increasing the relative importance of water's viscosity) — it is therefore possible that at least the long-spined chitinozoans were planktonic "floaters". On the other hand, the walls of some chitinozoans were probably too thick and dense to allow them to float. Whilst little is known about their interactions with other organisms, small holes in the tests of some chitinozoans are evidence that they were hosts to some parasites.[5][9][10] Although some forms have been reinterpreted as "pock-marks" caused by the disintegration of the diagenetic mineral pyrite, the clustering of cylindrical holes around the chamber — where the flesh of the organism was likely to be concentrated — is evidence for a biological cause. Corals in Gotland with daily growth markings have been found in association with abundant chitinozoans, which allow the detection of seasonal variation in chitinozoan abundance. A peak in abundance during the late autumn months is observed, with the maxima for different species occurring on different dates. Such a pattern is also observed in modern-day tropical zooplankton. The diversity of living habits is also reflected by the depth of water and distance from the shore. Different species are found in highest abundance at different depths. While deeper waters around 40 km from the shoreline are generally the optimal environment, some species appear to prefer very shallow water. On the whole, chitinozoans are less abundant in turbulent waters or reef environments, implying an aversion to such regimes when alive, if it is not an effect of sedimentary focusing. Chitinozoans also become rarer in shallower water - although the reverse is not necessarily true. They cannot survive freshwater input.

Tags: Вымершие одноклеточные, Девон |

| 06:11 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Tulerpeton Тулерпетон (Tulerpeton) — ископаемый род позднедевонских амфибий. Был впервые обнаружен в Тульской области, от которой и получил своё имя. Известен по практически польностью сохранившимся плечевому поясу, передним и задним конечностям, фрагментам черепа и другим мелким находкам. Тулерпетон достигал 50 см в длину, имел по 6 пальцев на каждой конечности и полностью утратил внутренние жабры. Строение скелета говорит о том, что он был более приспособленным к жизни на суше чем Акантостега, однако его ноги больше подходили для проталкивания туловища по мягкому влажному грунту, чем для ползания по земле. Находки тулерпетона были сделаны в морских отложениях, в то время как остальные ранние амфибии найдены в пресноводных. Это, возможно, указывает на длительное сохранение у амфибий физиологических механизмов адаптации к жизни в солёной воде и возможности пересекать моря, что позволило им распространиться уже в девоне вдоль всего экваториального пояса Земли. Tulerpeton lived approximately 365 million years ago, in the Late Devonian period when the climate was fairly warm and there were no glaciers. Land had already been colonized by plants. During the Devonian period, terrestrial tetrapods – the ancestors of present day reptiles, birds, amphibians and mammals - first began to appear. Even though Tulerpeton breathed air, it lived mainly in shallow marine water. The Andreyevka fossil bed where it was discovered was at least 200 km from the nearest landmass during this era. The fossils of plants in the area tell us that the salinity of the waters where it lived fluctuated wildly, indicating that the waters were quite shallow. Because the bones of the neck and the pectoral girdle were disconnected, Tulerpeton could lift its head. Therefore, in shallow water, it had a considerable advantage over the other animals whose heads only moved side to side. The later land animals that descended from Tulerpeton’s relatives needed this head flexion on land, but the condition probably evolved because of the advantage that this gave it in shallow marine waters, not for land. In the book “Vertebrate Life”, authors Pough, Janis, and Heiser say that,” The development of a distinct neck, with the loss of the opercular bones and the later gain of a specialized articulation between the skull and the vertebral column (not yet present in the earliest tetrapods), may be related to lifting the snout out of the water to breath air or to snap at prey items.” The six fingered hands and toes were stronger than the fins from which they developed, therefore “tulerpeton” had an advantage in propelling itself through shallow and brackish water, but the limbs do not yet seem strong enough for extensive use on land.

Tags: Антракозавры, Вымершие амфибии, Девон, Лабиринтодонты |

| 05:57 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Hynerpeton Hynerpeton (pronounced /haɪˈnɜrpətɒn/, from Greek Υνηρπετον "creeping animal from Hyner") was a basal carnivorous tetrapod that lived in the lakes and estuaries of the Late Devonian period around 360 million years ago. Like many primitive tetrapods, it is sometimes referred to as an "amphibian", though it is not a true member of the modern Lissamphibia. The Late Devonian saw the evolution of plants into trees and growing into vast forests pumping oxygen into the air, possibly giving Hynerpeton an edge because it evolved complex lungs to exploit it. Its lungs probably consisted of sacs like modern terrestrial vertebrates. In 1993, the paleontologists Ted Daeschler and Neil Shubin found the first Hynerpeton fossil, a shoulder bone, near Hyner, Pennsylvania. They were surveying the Devonian rocks of Pennsylvania in search of fossil evidence for the origin of animal limbs. The animal had a very robust shoulder, which indicated that it had powerful appendages. Only a few bones have been found from Hynerpeton, in Red Hill, Pennsylvania, U.S.A.. The known fossils include two shoulder girdles, two lower jaws, a jugal bone and some gastralia. The structure of the shoulder girdle indicates this animal may have been one of the earlier, more primitive tetrapods to evolve during the Devonian. Information on the relationship of the known fossils of Hynerpeton to other Devonian tetrapods can be found in Gaining Ground The Origin and Evolution of Tetrapods by Jennifer A. Clack. It is thought that that these early amphibians are descended from lobe-finned fish, such as Hyneria, whose stout fins evolved into legs and their swim bladder into lungs. It is still not known whether Hynerpeton is the direct ancestor to all later backboned land animals (including humans), but the fact that it had eight fingers, not five, suggests that it is simply our evolutionary cousin.

Tags: Вымершие амфибии, Девон, Ихтиостегалии, Лабиринтодонты |

| 05:37 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Elginerpeton Elginerpeton is a monotypic genus of early tetrapod, the fossils of which were recovered from Scat Craig, Scotland, in rocks dating to the late Devonian Period (Frasnian stage, 395 million years ago). The only known fossil has been given the name Elginerpeton pancheni. Elginerpeton is known from a partial skeleton including a partial shoulder and hip, a femur, tibia (lower hind limb), and jaw fragments. It is estimated to have measured about 1.5 m (5 ft) in length.

Tags: Вымершие амфибии, Девон, Ихтиостегалии, Лабиринтодонты |

| 05:15 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

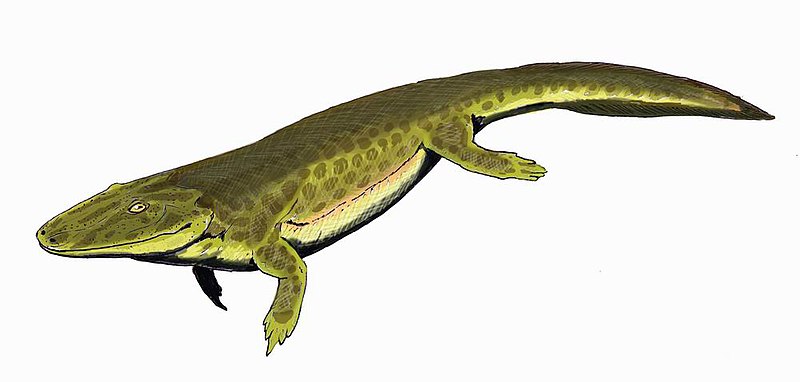

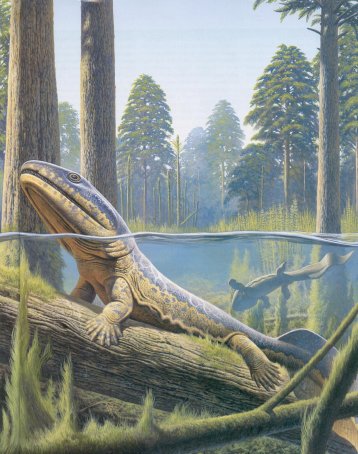

Ichthyostega Ихтиосте́га (лат. Ichthyostega) — род ранних тетрапод, живший в верхнем девонском периоде, около 367—362,5 млн лет назад, и представляющий собой первое промежуточное звено между рыбами и амфибиями. Этот род рассматривается в составе амфибий, однако он не является прямым предком современных видов, предки которых — лепоспондилы (Lepospondyli) — появились в каменноугольном периоде. У ихтиостегий были ноги, но их конечности, возможно, не использовались для ходьбы, а со временем были использованы для преодоления болот. Ихтиостеги имели хвостовой плавник и некоторые органы чувств, функционирующие только в воде. Тело их было покрыто мелкими чешуйками. По мнению некоторых учёных ихтиостеги наряду с определёнными видами кистепёрых рыб определили направление филогенеза в сторону возникновения наземных позвоночных. В 1932 году Сейв-Содерберг описал четыре вида ихтиостегий из верхнего девона, найденных в восточной части Гренландии и один вид принадлежащий роду Ichthyostegopsis, I. wimani. Эти виды могли быть синонимичными, потому что их морфлогические различия не были резко выражены. Виды различались в пропорциях и строении черепа. Сравнение было проведено на четырнадцати экземплярах, собранных в 1931 году Датской Восточной Гренландской Экспедицией. Дополнительные экземпляры были собраны между 1933 и 1955 годами. Род Ихтиостега находится в близком родстве с акантостегой (Acanthostega gunnari), также обнаруженной в восточной Гренландии. По сравнению с акантостегой череп ихтиостеги выглядит более рыбообразным, однако её пояс передних конечностей сильнее и лучше адаптирован к наземной жизни. Ихтиостеги были около 1,5 метров длиной и имели по семь пальцев на задних ногах. Точное количество пальцев на передних лапах пока не установлено, но вероятно, что их было тоже семь. На хвосте у них был плавник «рыбьего» типа поддерживаемый невральными и гемальными дугами. Ноздри располагались у нижнего края челюстей. Слезная кость примыкает к ноздре, но не к глазнице. Межвисочная кость отсутствует (это обстоятельство исключает возможность происхождения большинства темноспондилов от этого рода). Заднетеменная кость непарная. Челюстная кость соприкосается с квадратноскуловой. Сохраняются подкрышечные и предкрышечные кости. Носовые кости широкие. Глазницы овальные и располагаются в центральной части черепа. Хорда через отико-окципитальную часть мозговой коробки доходит до гипофизарной ямы. Early tetrapods like Ichthyostega and Acanthostega differed from animals like Crossopterygians (for instance Eusthenopteron or Panderichthys) in their increased adaptations for life on land. Though Crossopterygians possessed lungs, they used gills as their primary means of acquiring oxygen; Ichthyostega appears to have relied on its lungs as its primary apparatus for breathing. The skin of early tetrapods, unlike that of Crossopterygians, helped retain bodily fluids and deter desiccation. Crossopterygians used their body and tail for locomotion and their fins for balance; Ichthyostega used its limbs for locomotion and its tail for balance. The size of an adult Ichthyostega (1.5 m) precluded completely terrestrial locomotion. Yet the massive ribcage was made up of overlapping ribs and the animal possessed a stronger skeletal structure, a more rigid spine, and forelimbs apparently powerful enough to pull the body from the water. These anatomical modifications clearly evolved to handle the lack of buoyancy experienced on land. The hindlimbs were smaller than the forelimbs and unlikely to have born full weight in an adult, while the broad, overlapping ribs would have inhibited side-to-side movements. Jennifer A. Clack suggests that Ichthyostega and its relatives spent time basking in the sun to raise their body temperatures, much as some animals do today: the Marine Iguanas on the Galapagos Island or the Gharial. They would have returned to the water to cool themselves, hunt for food and reproduce. A lifestyle that required strong forelimbs to pull at least their anterior part out of the water, and a stronger ribcage and spine to support them while sunbathing on their abdomen like modern crocodiles. New studies suggests that the juveniles were more aquatic than the adults, and the possibility that Ichthyostega came out of the water only as a fully mature adult. Water was also still a requirement, because the gel-like eggs of the earliest terrestrial tetrapods couldn't survive out of water, so reproduction could not occur without it. Water was also needed for their larvae and external fertilization. Most land-dwelling vertebrates have since developed two methods of internal fertilization; either direct as seen in all amniotes and a few amphibians, or indirect for many salamanders by placing a spermatophore on the ground which then is picked up by the female salamander. The Ichthyostegalians (Elginerpeton, Acanthostega, Ichthyostega, etc.) were succeeded by temnospondyls and anthracosaurs, such as Eryops, amphibians that truly developed the ability to walk on land. Until 2002, there was a gap of 20 million years between the two groups ( Romer's Gap). In 2002 a 350 million year old fossil from the lower Mississippian, Pederpes finneyae was described and helped to close the gap: it is the earliest-known tetrapod to show the beginnings of terrestrial locomotion.

Репродукции (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6):

(Кстати, плаун, что показан тут на среднем плане был высотой до 8 метров.)

Размеры тела в сравнении с человеком:

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4):

Tags: Вымершие амфибии, Девон, Ихтиостегалии, Лабиринтодонты |

| 04:53 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Acanthostega В девоне появляются первые амфибии. Акантостега (Acanthostega) — род ископаемых тетрапод, живших в позднем девоне и являющихся промежуточным звеном между лопастепёрыми рыбами и наземными животными. Одни из первых хордовых, развивших конечности. Окаменевший череп акантостеги (Acanthostega gunneri) был обнаружен в восточной Гренландии в 1933 году, однако описан лишь в 1952 году Эриком Ярвиком. В 1987 году Дженифер Кларк были обнаружены новые фрагменты нескольких особей. Кости акантостеги были найдены в древних речных отложениях, предполагается что именно в реках эти животные и обитали. Акантостега достигала длины около 60 см. Конечности не имели запястий, что говорит о крайне низкой приспособленности к передвижению по суше, и на каждой из них насчитывалось 8 пальцев. Строение скелета указывает на наличие внутренних жабр. Слабые конечности, которые не смогли бы выдержать вес животного, и короткие рёбра, на которые оно также не могло опираться, говорят о его преимущественно водном образе жизни. Acanthostega had eight digits on each hand (the number of digits on the feet is unclear) linked by webbing, it lacked wrists, and was generally poorly adapted to come onto land. Acanthostega also had a remarkably fish-like shoulder and forelimb. The front foot of Acanthostega could not bend forward at the elbow, and thus could not be brought into a weight bearing position, appearing to be more suitable for paddling or for holding on to aquatic plants. It had lungs, but its ribs were too short to give support to its chest cavity out of water, and it also had gills which were internal and covered like those of fish, not external and naked like those of some modern amphibians which are almost wholly aquatic. Acanthostega is the first tetrapod to show the shift in locomotory dominance from the pectoral to pelvic girdle. There are many morphological changes that allowed the pelvic girdle of Acanthostega to become a weight-bearing structure. In more ancestral states the two sides of the girdle were not attached. In Acanthostega there in contact between the two dies and fusion of the girdle with the sacral rib of the vertebral column. These fusions would have made the pelvic region more powerful and equipped to counter the force of gravity when not supported by the buoyancy of and aquatic environment. Research based on analysis of the suture morphology in its skull indicates that the species may have bitten directly on prey at or near the water's edge. Markey and Marshall compared the skull with the skulls of fish, which use suction feeding as the primary method of prey capture, and creatures known to have used the direct biting on prey typical of terrestrial animals. Their results indicate that Acanthostega was adapted for what they call terrestrial-style feeding, strongly supporting the hypothesis that the terrestrial mode of feeding first emerged in aquatic animals. If correct, this shows an animal specialized for hunting and living in shallow waters in the line between land and water. Newer research also indicates that it is possible Acanthostega actually evolved from an ancestro that was more terrestrail adapted than itself. Acanthostega is seen as part of widespread speciation in the late Devonian period, starting with purely aquatic lobe-finned fish, with their successors showing increased air-breathing capability and related adaptions to the jaws and gills, as well as more muscular neck allowing freer movement of the head than fish have, and use of the fins to raise the body of the fish. These features are displayed by the earlier Tiktaalik, which like the Ichthyostega living around the same time as Acanthostega showed signs of greater abilities to move around on land, but is thought to have been primarily aquatic.

Репродукции (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6):

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6):

Tags: Вымершие амфибии, Девон, Ихтиостегалии, Лабиринтодонты |

| 04:23 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

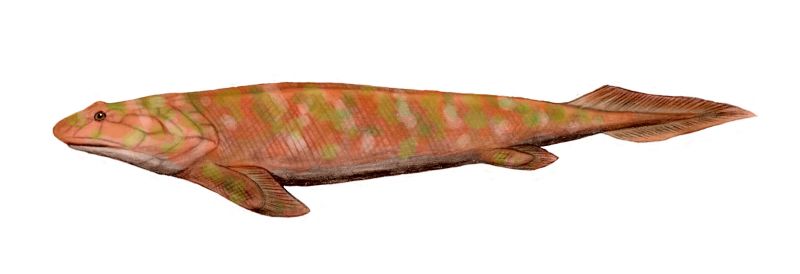

Cheirolepis Cheirolepis ('hand fin') is an extinct genus of ray-finned fish that lived in the Devonian period of Europe and North America. It is the only genus yet known within the family Cheirolepidae and the order Cheirolepiformes. It was among the most basal of the Devonian actinopterygians and is considered the first to possess the "standard" dermal cranial bones seen in later actinopterygians. Cheirolepis was a predatory freshwater fish about 55 centimetres (22 in) long. It had a streamlined body with small, triangular ganoid scales similar to those of the Acanthodii. Cheirolepis had well-developed fins which gave it speed and stability, and was probably an active predator. Based on the size of its eyes, it hunted by sight. Cheirolepis's jaws, lined with sharp teeth, could be opened very wide, allowing it to swallow prey two thirds of its own size. Six possible species of Cheirolepis are currently known. The type species, named in 1835, is C. trailli. Remains of this species have been found from Scotland and date back to the Eifelian and Givetian stages of the Middle Devonian. C. canadensis was described in 1881 from material found in Miguasha, Canada that dated back to the middle Frasnian stage of the Late Devonian. Two species, C. gracilis and C. gaugeri, have been found from Germany and Belarus in deposits that are of Givetian age. They were first described in 1973 from scale material that is now of questionable validity. Another species has been found from Belarus that lived during the Eifelian, and has been named C. sinualis. A new species has recently been described from a locality in Red Hill, Nevada deposited during the Mid-Late Devonian boundary. The specimen from which this species was named, consisting of scales and a lower jaw, was originally referred to C. canadensis. New, more complete specimens have shown it to be distinct from the type, although a species name is yet to be given for the remains.

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4):

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лучепёрые |

| September 28th, 2011 | |

| 08:25 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

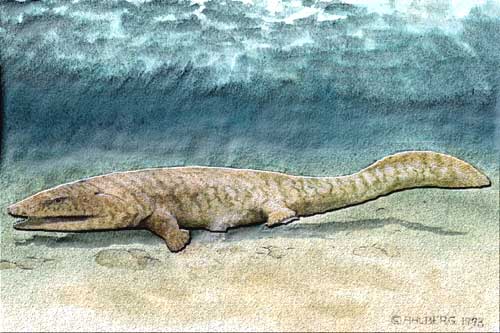

Ventastega Ventastega was a basal tetrapod that lived during the Famennian subdivision of the Late Devonian period approximately 374.5 to 359.2 million years ago, though Ventastega origins as a tetrapod lineage are probably seated in the preceding Frasnian period of the Late Devonian (385.3 to 374.5 million years ago) when a surge of morphological diversification of tetrapods began. Ventastega is one of the earliest Devonian tetrapods yet discovered. Given two preferred orientations of the bones and the geological context in which Ventastega was found suggests a tidal-sea influence. However, like Tiktaalik, Ventastega was probably more aquatic than terrestrial. Per Ahlberg, a professor of evolutionary biology at Uppsala University in Sweden reported in Nature that limbs, not fins were attached to Ventastega; this inference is based on the anatomy of key parts of its pelvis and its shoulders. The fossils reported were found in what is now western Latvia, Kurzeme/Courland peninsula. They are 365 million years old. A skull, shoulders, and part of the pelvis of the Ventastega curonica were found. They indicate it was more tetrapod than fish and looked similar to a small alligator. The discovery contributes to the understanding of the evolutionary transition from fish to tetrapods, the animals with four limbs, whose descendents include amphibians, reptiles, dinosaurs and birds, and mammals). Шведские палеонтологи из университета Упсалы (Uppsala Universitet) под руководством профессора Пера Алберга (Per Ahlberg) обнародовали результаты исследования окаменелых останков древнего существа. Учёные показали, что это — ещё одно недостающее звено между рыбами и четвероногими, вышедшими на сушу. Переход из воды на сушу произошел в конце девонского периода, между 360 и 380 миллионами лет назад, и потребовал множества изменений в строении организм рыб. Выявлением и восстановлением хронологии этих событий палеонтологи уже и занимаются порядка двадцати с лишним лет. К сожалению, скудность и фрагментарность ископаемых свидетельств до сих пор не позволяют поставить точку в этом вопросе. Останки этого вида рыб, живших примерно 385 миллионов лет назад, говорят о том, что они имели четыре конечности, заканчивающиеся плавниками; вероятно, эти плавники помогали ранним предкам четвероногих передвигаться по болотам или мелководью. Следующей за Ventastega ступенью развития является род Acanthostega, имеющий более выраженные конечности, заканчивающиеся пальцами. Эти тетраподы уже были способны к полноценной ходьбе по суше. Кроме того, к этому времени Земля знала еще несколько видов переходных звеньев между рыбами и земноводными, обладающих иными, более развитыми чертами строения тела. А значит, разделение тетраподов на классы и порядки могло начаться уже на стадии выхода рыб на сушу — гораздо раньше, чем прежде предполагали ученые.

Tags: Вымершие амфибии, Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Ихтиостегалии, Лабиринтодонты, Лопастепёрые |

| 08:00 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Tiktaalik Тиктаалик (Tiktaalik) — род ископаемых лопастепёрых рыб из позднего девона, имевших много общих черт с четвероногими. Название происходит от слова «налим» на языке инуктитут. Ископаемые останки были обнаружены в 2004 году на острове Элсмир (терр. Нунавут, север Канады). Тиктаалик является переходным звеном между рыбами и наземными позвоночными. В его строении сочетаются черты и тех, и других. Признаки, свойственные рыбам: Признаки с промежуточным состоянием:

Признаки, традиционно приписываемые четвероногим:

Tiktaalik lived approximately 375 million years ago. Paleontologists suggest that it is representative of the transition between non-tetrapod vertebrates ("fish") such as Panderichthys, known from fossils 380 million years old, and early tetrapods such as Acanthostega and Ichthyostega, known from fossils about 365 million years old. Its mixture of primitive "fish" and derived tetrapod characteristics led one of its discoverers, Neil Shubin, to characterize Tiktaalik as a "fishapod". The name Tiktaalik is an Inuktitut word meaning "burbot", a freshwater fish related to true cod. The "fishapod" genus received this name after a suggestion by Inuit elders of Canada's Nunavut Territory, where the fossil was discovered. The specific name roseae cryptically honours an anonymous donor. Tetrapod footprints found in Poland and reported in Nature in January 2010 were "securely dated" at 10 million years older than the oldest known elpistostegids (of which Tiktaalik is an example) implying that animals like Tiktaalik were "late-surviving relics" possessing features that actually evolved around 400 million years ago. Tiktaalik provides insights on the features of the extinct closest relatives of the tetrapods. Unlike many previous, more fishlike transitional fossils, Tiktaalik's "fins" have basic wrist bones and simple rays reminiscent of fingers. The homology of these is uncertain; there have been suggestions that they are homologous to digits, although this is incompatible with the digital arch developmental model because digits are supposed to be postaxial structures, and only three of the (reconstructed) eight rays of Tiktaalik are post-axial. They may have been weight bearing. Close examination of the joints show that although they probably were not used to walk, they were more than likely used to prop up the creature’s body, push up fashion. The bones of the fore fins show large muscle facets, suggesting that the fin was both muscular and had the ability to flex like a wrist joint. These wrist-like features would have helped anchor the creature to the bottom in fast moving current. Also notable are the spiracles on the top of the head, which suggest the creature had primitive lungs as well as gills. This would have been useful in shallow water, where higher water temperature would lower oxygen content. This development may have led to the evolution of a more robust ribcage, a key evolutionary trait of land living creatures. The more robust ribcage of Tiktaalik would have helped support the animal’s body any time it ventured outside a fully aquatic habitat. Tiktaalik also lacked a characteristic that most fishes have—bony plates in the gill area that restrict lateral head movement. This makes Tiktaalik the earliest known fish to have a neck, with the pectoral girdle separate from the skull. This would give the creature more freedom in hunting prey either on land or in the shallows Tiktaalik generally had the characteristics of a lobe-finned fish, but with front fins featuring arm-like skeletal structures more akin to a crocodile, including a shoulder, elbow, and wrist. The fossil discovered in 2004 did not include the rear fins and tail. It had rows of sharp teeth of a predator fish, and its neck was able to move independently of its body, which is not possible in other fish. The animal also had a flat skull resembling a crocodile's; eyes on top of its head, suggesting it spent a lot of time looking up; a neck and ribs similar to those of tetrapods, with the latter being used to support its body and aid in breathing via lungs; well developed jaws suitable for catching prey; and a small gill slit called a spiracle that, in more derived animals, became an ear. The fossils were found in the "Fram Formation", deposits of meandering stream systems near the Devonian equator, suggesting a benthic animal that lived on the bottom of shallow waters and perhaps even out of the water for short periods, with a skeleton indicating that it could support its body under the force of gravity whether in very shallow water or on land. At that period, for the first time, deciduous plants were flourishing and annually shedding leaves into the water, attracting small prey into warm oxygen-poor shallows that were difficult for larger fish to swim in. The discoverers said that in all likelihood, Tiktaalik flexed its proto-limbs primarily on the floor of streams and may have pulled itself onto the shore for brief periods. Neil Shubin and Ted Daeschler, the leaders of the team, have been searching Ellesmere Island for fossils since 1999.

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4, 5):

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| 07:55 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Strunius Strunius is an extinct genus of lobe-finned fish from the Devonian period of Germany. Although it was a lobe-finned fish Strunius's fins were supported by fin rays, which are more associated with ray-finned fish. However, its skull was composed of two articulating halves, a feature characteristic of the lobe-finned rhipidistians. The skull was also divided by a deep articulation, with both halves probably connected by a large muscle, increasing the power of the bite. The same system is seen in coelacanths and the better-known Eusthenopteron. Compared to other lobe-finned fishes, Strunius had a rather short, stubby body, and was just 10 centimetres (4 in) long. It was covered in large, round, bony scales, and probably fed on other fishes.

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| 07:33 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Scaumenacia Scaumenacia is an extinct genus of prehistoric sarcopterygian, or lobe-finned fish. Named after Scaumenac Bay (Baie d’Escuminac), the dipnoan fish Scaumenacia curta is the second most abundant sarcopterygian in the fossiliferous Escuminac Formation after Eusthenopteron foordi. Due to the large number of specimens, often complete, this species is one of the best known of all extinct dipnoi. The conditions for fossil preservation at Miguasha were favourable to Scaumenacia. For example, many skulls were preserved in three dimensions and show the complex pattern of the skull bones. In addition, some specimens were found with their meals still visible in the abdominal cavity. These stomach contents revealed a clear preference for Asmusia, a small crustacean protected by two shells. One such specimen, nicknamed La grande bouffe (a French reference to its enormous meal), had swallowed thousands before its death. With its large, rounded scales, its stocky body and short snout, Scaumenacia’s physiognomy is in some ways reminiscent of its distant descendant Neoceratodus, Australia’s living lungfish.

В левом нижнем углу.

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4):

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| 06:17 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Rhinodipterus Rhinodipterus is an extinct genus of prehistoric dipnoan sarcopterygian or lobe-finned fish, that lived in the Devonian Period, between 416 and 359 million years ago. It is believed to have inhabited shallow, salt-water reefs, and is one of the earliest known examples of marine lungfish. Research published in 2010 based on an exceptionally well-preserved specimen from the Gogo Formation of Australia has shown that Rhinodipterus has cranial ribs attached to its braincase and was probably adapted for air-breathing to some degree. This could be the only case known for a marine lungfish with air-breathing adpatations. Первые органы, с помощью которых двоякодышащие рыбы получали кислород из атмосферы, появились из-за глобального снижения его количества в атмосфере, а не из-за опреснения водоемов, как считалось ранее, сообщают австралийские ученые в работе, опубликованной в электронной версии журнала Biology Letters. Останки двоякодышащих рыб, обитавших на Земле 400-300 миллионов лет назад, ранее находили только в пресных водоемах. Поэтому считалось, что именно из-за более бедной кислородом пресной воды эти рыбы были вынуждены использовать для дыхания не только жабры, но и специальные пузыри, прообразы легких. Элис Клемент (Alice Clement) и Джон Лонг (John Long) из Австралийского национального университета (Australian National University’s Research School of Earth Sciences) обнаружили новый вид двоякодышащей рыбы Rhinodipterus при палеонтологических исследованиях формации древних рифов Гоугоу на западе Австралии. Этот вид, по словам ученых, – самая древняя из известных науке рыба этой группы, обитавшая в морской воде. Ученые обнаружили у рыбы ряд признаков, характерных для ее современных двоякодышащих сородичей, в частности, удлиненную полость рта, необходимую, чтобы удерживать большой воздушный пузырь, а также особое крепление краниальных (находящихся у головы) ребер. По предположению авторов, Rhinodipterus возникла примерно 375 миллионов лет назад в период, когда, по имеющимся данным, уровень кислорода в атмосфере упал до рекордно низких 12%. Именно это, как считают исследователи, и заставило рыб искать дополнительные способы дыхания: они не могли получить достаточное количество кислорода даже из морской воды. "Это снижение мировых уровней кислорода могло сильно повлиять на естественный отбор среди двоякодышащих и других существ, в том числе тетраподов – рыбоподобных предков наземных животных", – отметил профессор Лонг, слова которого приводит пресс-служба университета. Авторы пользовались данными о древней атмосфере, полученными Робертом Бернером (Robert Berner) из Йельского университета в 2006 году. Бернер построил на основе данных геологических наблюдений модель GEOCARBSULF, описывающую динамику уровней углекислого газа и кислорода в фанерозойский период (период истории Земли, начавшийся примерно 570 миллионов лет назад и продолжающийся до сих пор).

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| 06:11 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Quebecius Quebecius is an extinct genus of porolepiform sarcopterygian fish which lived during the Late Devonian period of Quebec, Canada. Quebecius differs from its fellow porolepiforms and most sarcopterygians in that it bears only one lobed fin, the pectoral fin, and its other fins sport rays that penetrate deeply into its body. Compared to osteolepiforms, porolepiforms are known for their small operculars, the plate-like bones that cover the gills of a fish. But in Quebecius, this bone is unusually small, even for a porolepiform. Furthermore, the epicercal form of its tail is much more pronounced than for other members of the group. Despite these differences, the species otherwise respects the relatively conservative morphology of porolepiforms.

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| 05:41 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Panderichthys Panderichthys is a 90–130 cm long fish from the Devonian period 397 million years ago, (Frasnian epoch) of Latvia. It is named after the german-baltic palaeontologist Christian Heinrich Pander. It has a large tetrapod-like head. Panderichthys exhibits transitional features between lobe-finned fishes and early tetrapods such as Acanthostega, and is considered the most crownward stem fish-tetrapod with paired fins. The evolution from fish to land dwelling tetrapods required many changes in anatomy and physiology, most importantly the legs and their supporting structure, the girdles. Well preserved fossils of Panderichthys clearly show these structures in transition, making Panderichthys a rare and important find in the history of life. One of the major changes in the appendicular skeleton during the transition from water to land was a shift in locomotory dominance from pectoral to pelvic appendages. Panderichthys is evidence of this because its morphology shows that the fin to limb transition began in the pectoral appendages and only later occurred in the pelvic appendages. Panderichthys is a good example of a transitional state in tetrapod evolution because its pectoral girdle shows derived characteristics while its pelvic girdle retains ancestral ones. Even though Panderichthys does not show the shift in locomotory dominance, it seems as though it was capable of some kind of shallow water or terrestrial body flexion locomotion and had the ability to prop itself up. Fish like Panderichthys were the ancestors of the first tetrapods, air-breathing, terrestrial animals from which the land vertebrates, including humans, are descended. The most notable characteristic of Panderichthys was its spiracle, a vertical tube used to breathe water through the top of its head, while its body was submerged in mud. This spiracle is a transitional organ that led, through evolution, to the development of the stirrup bone, one of the three bones (stirrup, hammer, and anvil) in the human middle ear. Recent reexamination of existing Panderichthys fossils using a CT scanner shows four very clearly differentiated distal radial bones at the end of the fin skeletal structure. These finger-like bones do not show joints and they are quite short, but nonetheless show an intermediate form between fully fish-like fins and tetrapods. In January 2010, Nature reported well-preserved and "securely dated" tetrapod tracks from Polish marine tidal flat sediments approximately 397 million years old. Therefore, Panderichthys can only be a "late-surviving relic", showing traits that evolved during the transition from fish-like creatures to tetrapods, but whose date does not reflect that transition. The tracks "force a radical reassessment of the timing, ecology and environmental setting of the fish–tetrapod transition, as well as the completeness of the body fossil record." Стройную теорию превращения «колючек» рыбьих плавников в пальцы наземных животных, казалось, разрушила найденная в Латвии окаменелая рыба, у которой этих костяшек не было. 20 лет спустя эстонские и шведские палеонтологи доказали, что тревога была ложной: компьютерная томография начала 1990-х не смогла распознать присутствовавшие в плавнике эволюционные зачатки пальцев. Panderichthys относится к эпохе начала позднего девона. Он обитал на Земле около 370 миллионов лет назад, примерно в одно время с тетраподами - ранними четвероногими обитателями Земли. И Panderichthys, и тетраподы произошли от одного предка. Его останки, как пишет Диена, были найдены в начале 70-х годов прошлого века недалеко от Цесиса. На них наткнулись в одном из карьеров Лоде. Год назад ученые приезжали в Ригу их изучать. Дело в том, что столь хорошо сохранившихся останков больше нет ни в одном музее мира. Ученые давно пришли к выводу, что элементы среднего уха, которое человек использует, чтобы усилить и передать звук, рыбы использовали для дыхания. А слуховая система возникла впервые у насекомых. Теперь исследователи опровергли это утверждение. К их удивлению, дыхальце и костная перегородка у Panderichthys оказались совсем не такими, как у других изученных ископаемых рыб. Расширенное дыхало, полагают исследователи, могло служить Panderichthys дыхательным каналом, как у современных акул и скатов. А если проще, то, в отличие от всех рыб, которые используют кости, аналогичные костям среднего уха, для дыхания, у Panderichthys они начали преобразовываться в ушные. Это значит, что мировой науке придется сдвигать момент образования ушей у животных на 10 миллионов лет. "Данная работа заполняет эволюционный промежуток, существовавший между рыбами и земноводными", - цитирует палеонтолога Тома Рича из Музея Виктории в Мельбурне (Австралия) Газета. ру. А палеонтолог позвоночных из Музея Карнеги в Питсбурге Же-Хи Ло (Пенсильвания, США) считает: "Теперь мы намного более ясно понимаем, где и когда эти особенности начали появляться. Это произошло ранее, чем мы думали".

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| September 27th, 2011 | |

| 08:51 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Osteolepis Osteolepis ('bone scale') is an extinct genus of lobe-finned fish from the Devonian period. It lived in the Orcadian Lakes of northern Scotland. Osteolepis was about 20 centimetres (7.9 in) long, and covered with large, square scales. The scales and plates on its head were covered in a thin layer of spongy, bony material called cosmine. This layer contained canals which were connected to sensory cells deeper in the skin. These canals ended in pores on the surface, and were probably for sensing vibrations in the water. Osteolepis was a rhipidistian, having a number of features in common with the tetrapods (land-dwelling vertebrates and their descendants), and was probably close to the base of the tetrapod family tree.

Ископаемые останки (1, 2, 3, 4, 5):

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| 08:21 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Onychodus Onychodus ( Onychodus was about 2 to 3 meters in length and was a pelagic animal. Like other onychodontiformes, it had a pair of tooth spirals (parasymphysial tooth whorls) bearing tusk-like teeth. The most well-preserved specimen of Onychodus has been found at the Gogo Formation of Western Australia giving palaeontologists more information about the structure of the fish. Other species of Onychodus are known only from poor material based on isolated tusks, teeth and scales. The most characteristic feature is a pair of retractable, laterally compressed tusk whorls at the front of the lower jaw. These were not attached to any other bone, but fit into a pair of deep cavities on the palate and were free to move. The lower jaw was connected with the upper jaw in a way that made the tusk whorl thrust out as a dagger when the head was raised. The upper jaw, containing 30 teeth which decrease in size posteriorly, is well preserved in many individuals. Juveniles have six tusks, while adults have three. A relatively complete specimen of Onychodus from Western Australia shows that its length was 47 cm long, the head being 10 cm in length with tusks 1.2 cm long. This specimen is only about half the size of larger individuals, since skulls measuring 19 cm in length have been found. However, a single tusk 4 cm long was found, showing that this specimen belonged to an even larger individual. Evidence found of the body reveals that a cross section of this fish would have been oval in shape. On the sides of the body, Onychodus had a series of pores which provided a sensory system that enabled the fish to locate prey and to position itself in narrow spaces. The tail fin is almost symmetrical around the vertebral column. It was rounded slightly and would have been very flexible with a broad sweep producing forward motion. A long fin extends posteriorly, along half the tail fin, forming the second dorsal fin. Evidence of the first dorsal fin is incomplete, but scientists believe that a fossil element found was its fin support. Ventrally, the large anal fin extends back beneath the anterior part of the tail fin. Scales that overlap anteriorly have been found, the smallest being only 5 mm across, and the largest 22 mm. Onychodus is the type genus of the order Onychodontida and the family Onychodontidae to which it belongs. The family name 'Onychodontidae' was created for Onychodus by the British palaeontologist Arthur Smith Woodward in 1891. The group of onychodontiformes, described in 1973 by the late Dr. Mahala Andrews, was characterized by a highly kinetic skull and tusk-like teeth. Suggestions by palaeontologist John A. Long refer to a close phylogenetic relationship between Onychodus and the basal lobe-finned fish Psarolepis from China. It is generally acknowledged that Onychodus and Psarolepis are both basal bony fishes, because of the absence of major features that unite coelacanths, lungfishes and tetrapod-like lobe-finned fishes. The position of Onychodus and Psarolepis in the cladogram is outside the major clade of sarcopterygians (lobe-finned fishes), but at a position m Many features of onychodont anatomy are known only from Onychodus itself. As other onychodontiformes, it has a highly kinetic and flexible skull. This unusual characteristic was due to the loose attachment of the skull bones, which sometimes overlapped, and were connected only by soft tissue and cartilage. Even the braincase was only partially made of bone. Other distinctive traits are related to the tusk whorls on the lower jaw. Because they could rotate, this was a different method of jaw articulation which did not compare with primitive ray-finned fish. The lower jaw was entirely articulated with cartilage, without an intermediate structure between the opposite sides, allowing the separation of the bones when prey was struck. Moreover, the loose articulation caused lateral movement, making the tusk walls move out of alignment. The parts of the lower jaw would have rotated inwards upon closing in order for the tusk whorls to fit exactly into the hollow spaces in the upper jaw. It is suggested that a ligament attachment and retractor mechanism existed in a pit under the tusk whorl, a unique condition in vertebrates. The capacity of the teeth on the lower jaw to fit with the tooth rows in the upper jaw, upon closure, kept the tusk whorls in place.ore derived than actinopterygians (ray-finned fishes). Through studies scientists believe that Onychodus was an ambush predator. John A. Long has suggested that Onychodus probably hid in the Devonian reefs, lunging at its prey as it swam by. A fossil specimen of Onychodus from Western Australia was found with a placoderm fish half its length logged in its throat. This interesting find was described and illustrated by Dr. John A. Long. The pectoral fins were strong enough for the animal to "walk" around the sea floor in search of a hiding place between coral colonies. The posterior dorsal fin was quite powerful, providing quick speed for capturing prey.

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| 08:12 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Miguashaia Miguashaia is a genus of prehistoric lobe-finned fish which lived during the Devonian period. Miguashaia is the most primitive coelacanth fish. Miguashaia bureaui is the most primitive of all the actinistian fishes. Instead of having three lobes, its tail was epicercal. And in the adult, the anal fin had almost no fleshy lobe, whereas the second dorsal fin had none at all. The present-day coelacanth, Latimeria chalumnae, has a very monotonous diet. In complete darkness, it hovers vertically with its head down deep in the Indian Ocean, skimming the bottom in search of prey. Thanks to a rostral organ at the tip of its muzzle, it can detect natural electric fields generated by small animals like crustaceans and other invertebrates. Once a potential meal is located, the coelacanth drops downwards and swallows it. The central tail lobe is what allows the fish to perform this delicate manoeuvre, known as headstand feeding.

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |

| 07:47 pm [industrialterro] [Link] |

Laccognathus Laccognathus — род вымерших лопастепёрых рыб семейства Holoptychiidae. Были распространены в Европе и Северной Америке в девонском периоде (375 миллионов лет назад). Размеры тела достигали 2 метров. У рыб была большая плоская голова с мощным ртом и маленькими глазами. Предположительный образ жизни: придонные хищники, подстерегавшие жертву в засаде. Species of Laccognathus were characterized by the presence of three large pits (fossae) on the external surface of the lower jaw which may have had sensory functions. It is the origin of the genus name, from Greek λάκκος ('pit') and γνάθος ('jaw'). Laccognathus grew to approximately 1–2 metres (3.3–6.6 ft) in length. They had very short dorsoventrally flattened heads, less than one-fifth the length of the body. Like other sarcopterygians, their fins arise from pairs of fleshy lobes. The skeleton of Laccognathus was structured such that large areas of the skin were stretched out over solid plates of bone. This bone was composed of particularly dense fibers-- so dense that cutaneous respiration (exchange of oxygen through the skin) was not a likely trait exhibited by Laccognathus. Rather, the dense ossifications served to retain water inside the body as Laccognathus traveled on land between bodies of water. Laccognathus are classified under the family Holoptychiidae in the extinct order Porolepiformes. They are not direct ancestors of tetrapods like the clade Tetrapodomorpha, but instead belong to the clade Dipnomorpha. Their closest living descendants are the members of the subclass Dipnoi (lungfishes).

Tags: Вымершие рыбы, Девон, Лопастепёрые |